The typical flight in a personal airplane is uneventful. We take off, fly the mission and land. Every now and then, though, stuff happens. It’s one of the reasons flying has been called “hours and hours of boredom punctuated by moments of sheer terror,” a description it shares with many other activities. In fact, most of us have our own tales to tell, stories of airborne drama we’ve experienced personally or heard directly from the people involved.

I’ve been doing a lot of flying recently, spending quality time at airports and remote landing strips with other pilots and their airplanes. Along the way, I picked up several “there I was” narratives from pilots who made serious errors in judgment, plus others who experienced what can only be described as bad luck. Sharing these narratives with other pilots helps add to our knowledge of what can happen, how we should prepare for it and what we can do in response. In reflecting on them, I soon realized they all have a common element. And since I was the pilot for one such event, I can assure you: When an event begins, it often happens very quickly, providing little warning.

| Commonalities |

|---|

| Each of the events described share some common themes: |

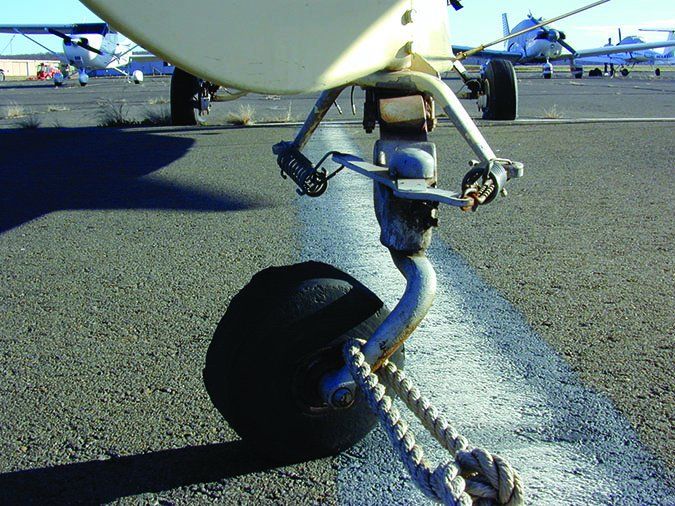

| TAILDRAGGERS |

| Each airplane involved was a conventional-gear design, and what happened can be traced to poor ground visibility and planning, plus remote, unconventional runways for which taildraggers are well-suited. |

| MAX-PERFORMANCE MANEUVERING |

| In many of these events, the pilot was attempting an operation approaching the limits of the airplane’s performance, and perhaps of his or her skills. |

| AN AUDIENCE |

| If you can pull it off, you’ll look great. If not, you’ll look like a goat. At least someone will be available to call 911. |

Staggerwings

We’ll start with what might be the unthinkable, at least for those of us who value antique aircraft, and probably for the pilots involved. It happened toward the end of a fly-in devoted to radial-engine powered airplanes, the Round Engine Round-up. Two 1930s-era Beechcraft Staggerwings were taxiing together for a formation photo flight. The lead airplane, a red Staggerwing, was using the right side of the taxiway, with a blue and yellow one following on the left side. Both pilots were extremely competent, well-briefed and in control.

But Staggerwings have a notorious blind spot on the right, particularly during ground operations. The trailing pilot knew this; he also knew the rule of thumb saying that, when in formation, keep your eyes on the lead at all times. Just as they approached the “hold short” line, there was an unclear communication. The front plane stopped, and the pilot behind and to his left momentarily lost sight. He hesitated, and in the moment of lapsed attention, his prop chewed through the red Staggerwing’s left wings.

Fortunately, the lead airplane’s wing-mounted fuel tank wasn’t hit and no one was injured, though every Staggerwing admirer died a little inside. Details from the NTSB, along with images of the aftermath, are on the opposite page.

Travails Of Taking Off

Taxiing usually doesn’t result in such drama, but certainly requires our undivided attention. So it also is with takeoffs, which often are not treated with the respect they deserve, in favor of landings. Both require planning and attention, but only one uses full power.

A Cessna 185’s pilot was attempting a takeoff from a remote roadway. Presumably the “runway” was of adequate dimensions but the pilot didn’t notice the fence and cattle guard at the departure end until seconds before hitting them. The collision sheared off one of the plane’s horizontal stabilizers. However, the airplane remained (at least somewhat) controllable and safely landed at its home airport.

In another off-pavement tale, the pilot of an Aviat Husky was attempting to take off from a back-country runway. With brakes applied, the pilot added full power, raising the tail off the ground. But the pilot released the brakes asymmetrically, causing the airplane to track away from the runway centerline toward its edge. The takeoff attempt ended when the Husky’s left wing impacted a haystack and its prop hit adjacent farm equipment.

In our final takeoff tale, an ultralight pilot was attempting to depart a private airstrip. Concerned about power lines at the far end of the runway, the pilot continued applying back pressure after lift off. At about 50 feet agl, the craft was losing speed and mushing. Inevitably, it stalled and spun to the ground, but the pilot was not seriously injured and walked away.

Landing Excitement

What goes up must come down, and after we take off, a landing always follows. What varies is the landing’s quality and ultimate outcome. And like our tales of takeoffs, landings attract their fair share of troubles.

Our first example involves an experimental biplane, a short-coupled taildragger. Its pilot was landing at a destination popular for its good barbecue and perhaps was acutely aware he would have an audience. He also may have been attempting to demonstrate the airplane’s short-field landing capability. The plane approached at what witnesses described as an extremely slow speed, touching down on the grass runway just past its threshold. So far, so good. But then it immediately ground-looped, coming to a stop with outboard wing and skin damage.

Elsewhere, a group of planes circled a private airstrip in early winter, their pilots discussing the runway’s condition on the air-to-air frequency. One pilot elected to touch his Husky’s wheels to see if the strip was usable. The plane’s main wheels grabbed the snow and the Husky flipped over. The pilot was not injured. The remaining pilots landed elsewhere and summoned help.

A Piper Cub pilot offered to let a pilot-rated passenger land his plane. The first two landings were textbook wheel landings. The last was to be a three-point landing. The plane touched down with all three wheels aligned with the center line but then began veering toward the runway’s edge. The pilot took over, but too late, and aggressively applied the brakes just as the plane rolled onto the runway’s softer edge. The Cub remained upright, but the nose-over resulted in the destruction of a beautiful hand-finished wooden prop.

June 28, 2015, Idaho Falls, Idaho

Two Beechcraft Staggerwings

While taxiing as lead of a flight of two, the pilot of the red Staggerwing stopped his airplane to perform a checklist. The pilot of the blue Beechcraft following lost visual contact with the lead while changing frequencies on his radio. His airplane’s propeller contacted the left aft section of the red Staggerwing, which resulted in substantial damage to its left wing. Both pilots reported there were no pre-impact mechanical failures or malfunctions with their airplanes.

September 21, 2015, Idaho Falls, Idaho

Cessna T206H Turbo Stationair

At about 200 feet agl in the initial climb, the passenger noticed smoke. The pilot initiated a turn to the crosswind pattern leg as it rapidly filled the cabin. Soon, smoke was obscuring the instrument panel.

The pilot saw the runway and turned the airplane toward it. He opened his side window and put his head outside for a better view, then pushed the nose down to approach the runway. As soon as the airplane touched down, he applied full braking, skidding a tire.

Once the airplane came to a stop, the pilot pulled the mixture control and the two aboard rapidly egressed. The flight instructor and passenger/camera operator sustained minor injuries related to smoke inhalation.

The Moral

All of these events I either witnessed or learned about from one or more of the people involved. And in the last example, I was the Cub pilot. In each case, pilots seemingly were in control and everything seemed okay. A moment later, things went terribly wrong. Fortunately, they all ended without major injuries, other than to pilot pride.

The sidebar on page 10 lists common elements of these real-world stories, but the thing I want to highlight is they all happened quickly, with little warning. The punchline: It only takes a moment of inattentiveness, loss of focus or just plain bad luck for the story to be about you.

Mike Hart is an Idaho-based commercial/IFR pilot and proud owner of a 1946 Piper J3 Cub and a Cessna 180. He also is the Idaho liaison to the Recreational Aviation Foundation.