This I know: If you see something with your own two eyes, you probably can avoid it. Happened to me just last month. A regional airliner, working with ATC, was approaching its destination. I was working my way around the Class C airspace, at the center of which the airliner was aimed.

I saw him first as an ADS-B target on my EFIS screen, a simple white diamond with a predicted (that’s important) trajectory, some 20 miles away. I looked up to search for him in my windscreen, even so. I always look up and out, no matter my flight conditions. Here’s why: Closing speeds what they were (around 450 knots), the distance between us closed in what felt like an instant. And there he was, right where I’d guessed and where ADS-B predicted.

As I always do in or around congested airspace, I was listening to ATC, though that day I was not participating in traffic sequencing. There really was no need, since I was on my way around the airspace to my uncontrolled airport just north of the city. I knew the routes, and where to look for predicted traffic. I heard myself called as traffic to the airliner, and then called as a traffic alert.

I kept my own trajectory predictable, so that ATC would be able to give him a good vector away from me. Except ATC didn’t. Instead, I got to see what a nice paint job this CRJ had—and that the co-pilot was wearing Ray-Bans. This happened because the airliner pilots, who apparently did not get any conflict resolution advice from either ATC or their onboard TCAS, decided to make their avoidance turn directly into my avoidance turn. Yep, our first move was into each other, quite by accident, and most likely because the copilot of the jet was flying and he wanted to keep me in sight as he attempted to avoid me. My next move was an abrupt turn and climb in the other direction, and the RJ passed underneath.

Why did this seemingly simple encounter turn into a near-miss? I suspect it’s because the jet’s crew was following ATC instructions on an IFR flight plan. Even though it was severe clear and there was sophisticated TCAS equipment aboard, no one in that cockpit actually saw me until the last moment. Thank goodness at least one pilot (me) was looking outside.

Oh, the things you will see!

Looking out the window when I fly isn’t all about seeing the scenery. Even in instrument conditions, I scan outside the airplane as part of my cross-check of the instrument panel. I’m looking for traffic, towering, dark clouds I prefer to deviate around, and of course, on the approach I’m looking for the runway. Yes, I scan for the runway throughout the course of even precision approaches, because I want to transition properly the moment I see it and its environment. If I’ve got a copilot, well, I may assign the outside scanning duties to him/her. But believe me, in every airplane I fly, someone is looking outside.

I do it because, frankly, it makes me a safer pilot. You see amazing things when you look outside. Just the other day, tooling along at 10,500 feet, I saw parachute canopies…lots of them. They were about a mile and a half away, and clearly the group was working to perform a “stack” formation. Fascinating—and I’m glad I saw it and didn’t fly into it!

I’ve seen rocket launches arc above me as they pierce the sky, and less benign phenomena such as waterspouts and roll clouds coming my way. And I’ve seen other aircraft, a few at far closer range than I was truly comfortable. I’ve learned by looking outside that not every aircraft in the sky has a transponder squawking. Ergo, I’m not going to see every possible bit of traffic repeated on my EFIS screen in the cockpit. There are still plenty of aircraft with transponders that have to be manually switched to Mode C when they take off (and there are still plenty of pilots who forget to do that).

I’ve also seen when my instrumentation isn’t providing me with good information. Remember, GPS relies on clear reception of a series of satellites, and ground-based navigation shuts down on occasion, as well. Even my compass and magnetometers have been thrown off by iron deposits beneath my airplane. Sometimes pilotage is an absolute necessity, if only to back up the colorful screens that might be lighting up your cockpit with information.

A Cautionary Tale

Occasionally the problem isn’t that the pilots are not looking outside; sometimes the real issue is that you’ve got to understand, process and respond to what you see outside the airplane, then react accordingly. Let’s take a look at one of the most onerous of recent accidents caused both by over-reliance on the technology inside an airplane, and the pilots’ failure to understand what the outside picture was telling them.

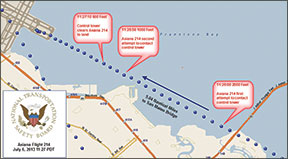

Asiana Airlines lost a Boeing 777 at San Francisco International Airport (KSFO) while trying to land on July 6, 2013, despite more than 20,000 hours of pilot experience in the cockpit and millions of dollars of technology in the instrument panel and under the floor. The pilots, three of them, one of them a training captain (check airman), allowed their Triple-7 to fly into a seawall. The sidebar on the previous page includes some of the details.

The reason these pilots hit that seawall instead of touching down on the runway is appallingly clear from reading the transcripts and looking over the graphics surrounding the accident: They appeared not to have an understanding of their trajectory, with one exception. The cockpit voice recorder transcript persuades me to cut the reserve first officer a break.

He was sitting on the jumpseat, and pointed out first the aircraft’s position high on the approach, then the excessive sink rate and deteriorating airspeed of the craft caused by the captain’s corrections. He spoke up to his captains no less than three times in the last three minutes of the flight, but always politely, and never, it seems from the transcript (hard to tell) with authority. His comments were acknowledged, but no changes were made. The training captain let his trainee fly until two seconds before they hit the seawall, at which point he attempted a go-around, but the momentum of such a heavy aircraft being what it is, his actions were just too late.

The ability to understand inertia and momentum—which, when properly managed on a glideslope, leads to a stable approach and smooth landing—is a basic pilot instinct, one borne in the seat of one’s pants and practiced by interpreting what one’s eyes are telling them on landing after landing, until one gets it right.

Except that many straight-to-airline ab initio pilots do not train that way anymore. They spend few hours in an actual airborne cockpit learning and then practicing their craft in a visual environment. Instead they spend countless hours in sophisticated simulators and flight training devices, learning the systems and how to manage them. They are taught to let the computers fly the airplane—and land it.

There was no ground-based navigation system operating the day Asiana 214 came up short at KSFO, but they still could have programmed the airplane properly and it would have landed. They could have heeded the jumpseater’s callouts and corrected their error and it would have landed. They didn’t.

The Takeaway

How does this story pertain to your light airplane flight? Think about it. If you fly with what I like to call “pretty pictures,” more often known as EFIS, PFDs or MFDs, or even Garmin/iPad GPS moving maps on your lap or clamped to your yoke, please remember this: The pictures you see on a glass-panel screen are just representations of the world outside, generated by the fancy coding of a human computer engineer, not necessarily a pilot. They are as up-to-date and accurate as your last update and that human somewhere who input the information.

Nexrad weather is generally 10 to 15 minutes old when it displays on your EFIS or iPad screen. I’ve seen days where the storms moved far too quickly for Nexrad—by looking outside I could see the rain shafts were off by miles from where they were depicted on my screens. Pilots are still flying into destructive weather because they don’t seem to understand this simple fact: Nexrad is for avoidance, and is not a good tool for trying to pick your way through embedded storms in IFR conditions.

Know that even GPS isn’t always as reliable as we have come to believe. Maps of terrain can be offset slightly (do you test this by occasionally flying directly over a known point?). Sunspots, solar flares and electromagnetic storms can shut down signals. Older, non-WAAS boxes need to check RAIM for each flight, and RAIM can fail. Recently my older Garmin GNC 300XL began rebooting itself at the most inopportune moments, such as on lifting off for an IFR flight the other day. Good thing I had the clearance written down on my lapboard and programmed into all three GPS moving map devices in my cockpit. Even Dr. Hilton Goldstein—founder and developer of WingXPro7—carries an iPad mini to backup his iPad, which backs up his in-panel navigational instrumentation. Yep, triple redundancy is a good thing when you are counting on TAA to get you there. I say save some money and use your eyes!

Even scarier, I think, is what can happen on approach. I’ve seen the pretty boxes of the virtual glideslope on my EFIS fail to consider the trees that have grown up and into a runway’s clear zone (how would it know?). The computer generated glideslope at my home airport does not line up directly with the runway, it turns out. I’ve never been able to figure out why. I just know and adjust. Sometimes VFR is the only way to go.

Meanwhile, neither ADS-B or even active traffic systems can pick up aircraft without transponders, as I pointed out earlier. I know from looking out my windscreen that plenty of traffic opt out. And digital autopilots, newfangled auto-throttles, FADEC and the like? They are only as good as the pilot’s knowledge of their intricacies and fallacies (this technology, it turns out, is what really bit the Asiana pilots in their collective butts).

Old-fashioned?

Bottom line, the technology in my instrument panel gives me wonderful capabilities, but they are only as good as my complete understanding of how to use them, and when. Above all, I need to be able to fly my airplane, first. I was taught to use my kinesthetic senses and my eyes looking outside the aircraft when I fly, no matter the conditions. Call me old-fashioned, but it works.

Oh, one more thing. I listen to my copilot when he tells me there might be a problem. Even pinch-hitters (non-pilot copilots who fly with you all the time) can perceive issues before they become big problems in flight. They are great traffic and ground-spotters, and they’ll tell you when they think you are fatigued, too. So listen and respond.

If you’ve got a little time on your hands and you are curious, do what I do to learn from other’s mistakes in aviation. Look over the records at the NTSB’s Web site, www.ntsb.gov, including both preliminary reports and those for which a probable cause finding has been made. Back that up with the recent accident recaps elsewhere in these pages. I promise it’ll make you a believer in looking outside, for more than just the scenery, too.

The NTSB On Asiana 214

“Human factors research has demonstrated that system operators often become complacent about monitoring highly reliable automated systems when they develop a high degree of trust in those systems and when manual tasks compete with automated tasks for operator attention. This phenomenon occurs in both beginner and expert operators and cannot easily be overcome through practice (Parasuraman and Manzey 2010, 381-410)….

However, the use of such systems has predictable adverse consequences on human performance. Specifically, it reduces monitoring and decreases the likelihood that a human operator will detect signs of anomalous or unexpected system behavior involving the processes under automatic control. In this case, the PF, PM, and observer believed the A/T system was controlling speed with thrust, they had a high degree of trust in the automated system, and they did not closely monitor these parameters during a period of elevated workload.”

Trust, But Verify

There’s little question that today’s avionics offer more capability and utility than ever before. But many of their advanced functions are only advisory in nature: Pilots still must look out the window to verify what they’re telling us. Two examples of the ways they can trip are depicted at right.

At top, an Avidyne EX600 displays nearby ADS-B-generated traffic data, including call signs, relative altitude and rate of climb, and predicted trajectory. Bottom, a Garmin G1000 multi-function display panel presents a complicated, large-scale view of weather over southern Florida.

In neither instance should pilots depend on these representations. Yes, they’re much more accurate and complete than anything that’s come before, but they still incorporate errors, chief among them are non-participating traffic—and even aircraft lacking electrical systems—or rapidly building/moving storms Nexrad won’t tell you about until the next update. The only way to verify what either box tells you is to look out the window.