It’s a moment you probably won’t forget. After your instructor handed back your signed logbook and reached for the cockpit door, he or she reminded you, “If anything about the landing doesn’t look right, just go around.”

You wouldn’t have gotten that solo endorsement without first convincing your CFI that you could not only tell when to break off an approach to try again, but actually manage it consistently. Still, every year, three or four dozen airplanes and a handful of helicopters are wrecked by pilots unsuccessfully trying to do just that. Somewhere between that first stage check and life after adult supervision, something’s getting lost.

Wait and Hurry Up

The sidebar on the opposite page details some recent accident resulting from botched go-arounds. Of them, the Baron and Arrow accidents in particular suggest their pilots succumbed to a startle response. Odds are that both were focused on making their landings to the exclusion of everything else, so the need (or perceived need) to go around came as a shock to which they reacted abruptly. Like the Cirrus pilot, they let their airplanes get into precarious situations without revising their plans. Nearly half the runway had already passed beneath the Baron’s wheels without it slowing enough to land. The Arrow got down to 50 feet while clearly coming up short.

Hurrying the procedure and waiting too long to begin it can each be enough to turn a good flight bad, but of course they often come as a package: the late start creates an unnecessary sense of urgency. Remember your instructor telling you that you should always be ready to go around? That’s one of the lessons that seems to be too easily forgotten after the checkride. Even when it’s forced by something unexpected—deer on the runway, or a student pilot cutting you off on short final—no go-around should come as a complete surprise. And it’s not an emergency and should never feel like one. The airplane’s either still flying or was very recently, and you know what it takes to keep it airborne or start it flying again. George Perry, who gave GA flight instruction before, during, and after a Navy career that included sticking some 900 carrier landings at the controls of F-14s and F-18s, puts it succinctly: “You don’t have to climb right now. You just have to not land.” Stay cool and take it one step at a time.

Rushing any procedure multiplies opportunities to get it wrong—to miss necessary steps or mix up their order, over- or undercontrol and then overcorrect for the errors, or just let the aircraft get away. The examples illustrate the specific ways haste makes waste when going around: jamming in too much power too fast, hauling back the yoke too hard and/or early, forgetting trim and rudder, and maybe pulling off all the flaps (or none) instead of easing them out in increments.

Naturally, it’s easier to be calm and methodical if you give yourself the luxury of an early start. Airspeed plus altitude equals options. The physics of the transition from a stable 500 fpm descent at low power with nose-up trim to a stable 500 fpm climb at full power are exactly the same whether it’s done just after turning final or over the numbers … but the latter’s more likely to trigger an unhelpful surge of adrenaline.

Don’t Fear Commitment

Your love life is your own business, but commitment to a go-around should be immediate and absolute. Once you’ve begun, don’t even think about changing your mind. (The same applies to IFR missed approaches.) Whatever put a safe landing in doubt has not gotten better during the time terra firma’s been getting farther away while the runway’s far threshold drew nearer. Conversely, the more airspeed and/or altitude you’ve regained, the closer you are to making a clean getaway. This is no time for second thoughts. You started it, you finish it.

Like a Bike

Have you ever heard a pilot brag about only doing go-arounds when required during flight reviews? It’s probably intended as a boast of superior airmanship—more likely along the lines of “I can salvage any approach” than “all my approaches are stabilized”—but it’s fair to ask whether he or she would be just as proud of never landing in a crosswind. Is it really a virtue to neglect an essential, potentially life-saving technique? Executing an uneventful go-around is probably easier than riding a bicycle, but neither skill stays sharp indefinitely without being exercised.

Assuming you do some kind of recurrent training (please tell us you do!), make a point of including planned go-arounds while you’re banging around the pattern or after maneuver practice. Missed approaches during hood work can serve the same purpose, especially from procedures with low MDAs or decision heights. Even if you’re flying solo, it’s okay to say it out loud: “This time, I’m going around.” If it’s been a while, plan to start the first one early—say, 300 or 400 feet agl after turning final—so you won’t feel rushed. If it’s a non-event, great. If some rust shows, do a couple more at progressively lower altitudes until you’re entirely comfortable again. After that, encourage your safety pilot, instructor or other cockpit companion to call “Go around!” unexpectedly every once in a while. That way you’ll have it when you actually need it.

The fact that pilots don’t always manage to go around may not be quite as perplexing as the fact that aircraft are still lost to fuel exhaustion, but it comes close. It’s another reminder that nothing in aviation is automatic except gravity and drag, that it’s better for your mind to get ahead of your airplane than vice versa, and that no skill improves without practice. It’s also a reminder that most accidents fall into that broad category of Things That Never Have to Happen. No reasonably attentive pilot should lose control or hit the trees trying to go around. After all, we mastered it before our first solos.

How to Do It…Right

The first step in not landing is to stop coming down. That means increasing thrust without sacrificing airspeed. Most light airplanes react to added power by pitching up, so don’t open the throttle any faster than you can compensate with forward pressure and trim. Coordinate that with enough rudder to keep the nose straight—wow, you’ve got both hands and one foot all working at once! It may be necessary to trade a little more altitude for airspeed in order to arrest the descent. Once the engine’s at full power and the nose is level, retract the first notch of flaps and then the gear (if that’s an option). If the airplane begins settling, resist the urge to pull back; instead, lower the nose to build airspeed. Once above rotation speed it’s a straightforward transition to a normal climb, retracting flaps in increments while accelerating at least to VX.

The more powerful the aircraft, the more crucial it is to handle it gently so thrust and torque won’t outmuscle control inputs. With 250 or 300 horses under the cowling, slamming the throttle into the firewall brings out the bucking bronco in even otherwise well-behaved machines like Bonanzas or Cessna 210s. The beast rears, snorts, and twists in an effort to throw off its rider. Be kind to your mount if you want it to be kind to you.

How To Do It…Wrong

So how did almost 400 pilots over the past decade manage to botch a basic private pilot maneuver badly enough to earn spots in the NTSB database? A quick look at a few of those reports offers some insights:

Bolingbrook, Illinois, September 20, 2013

During an attempt to land with an eight-knot quartering tailwind, the Cirrus SR20 “touched down multiple times about halfway down the runway,” then lifted off, turned left at low altitude, “descended with the wings level as it flew over a few buildings…then struck a tree and a light pole.” The crash ignited a fire that consumed most of the airplane.

Lagrange, Georgia, February 22, 2014

The Beech Baron B55 came in fast after a practice ILS and floated at least 2000 feet past the threshold. The pilot reacted to a perceived conflict with a glider tow on an intersecting runway by immediately going to full power. The airplane pitched up an estimated 60 degrees, “banked left, rolled inverted, and struck the ground in a nearly vertical nose-down attitude.” The glider stopped short of the intersection; the tow plane crossed it behind the Baron.

Terrell, Texas, January 19, 2016

During a simulated engine-out approach in a gusty crosswind, the instructor called for a go-around at about 50 feet agl. The private pilot flying the Piper Arrow IV “simultaneously pulled back and went full throttle…[and] the airplane fell straight to the ground,” bounced, and rolled onto the runway, where the left main gear collapsed.

Nashville, Tennessee, March 20, 2016

The Cessna 172 began drifting right during the flare. “The pilot…determined ‘it was not safe to land’ and applied full power to go around and subsequently retracted the flaps from 30 degrees to zero degrees…. The airplane was unable to gain altitude or airspeed and touched down in the grass next to the runway.”

Between them, these examples display the characteristic mechanisms of most go-around accidents: some combination of stalls, lateral excursions, excessive delays, and configuration errors. But it’s one thing to know how these accidents happen, another to understand why.

Three Things To Get Right

The FAA’s Airplane Flying Handbook (FAA-H-8083-3B) says there are three basic elements to go-arounds:

Power

“The instant a pilot decides to go around, full or maximum allowable takeoff power must be applied smoothly and without hesitation and held until flying speed and controllability are restored. Applying only partial power in a go-around is never appropriate.”

Attitude

“The airplane executing a go-around must be maintained in an attitude that permits a buildup of airspeed well beyond the stall point before any effort is made to gain altitude or to execute a turn. Raising the nose too early could result in a stall from which the airplane could not be recovered if the go-around is performed at a low altitude.”

Configuration

“Caution must be used in retracting the flaps. Depending on the airplane’s altitude and airspeed, it is wise to retract the flaps intermittently in small increments to allow time for the airplane to accelerate progressively as they are being raised. A sudden and complete retraction of the flaps could cause a loss of lift resulting in the airplane settling into the ground.”

When It Really Is Too Late

Regardless of the length or environment of the runway, there’ll come a point where climbing out again is no longer feasible: the airplane either can’t climb steeply enough to clear obstructions or is on the ground without enough runway to regain flying speed. This becomes easier to recognize with experience in that particular aircraft, reinforcing that the first key to unexciting go-arounds is deciding early, with airspeed and altitude to spare.

It’s not an easy decision even when you’ve clearly waited too long…but once you feel that sickening sense of doubt, it’s time to forget the airplane’s survival and concentrate on your own. Top priorities are shedding as much velocity as possible—remember, impact forces increase with the square of speed—while maintaining control. Keep it on the ground if you’re there and get it down if you’re not—then throttle to idle, stand on the brakes, and full aft stick for aerodynamic braking once you’re slow enough to not lift off again. Use the rudder to delay head-on impact with anything solid as long as possible, even if it means shearing off the wings (which also dissipates energy before a collision).

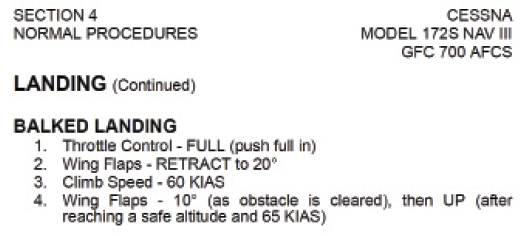

Procedure Matters

The goal’s straightforward enough: arrest the descent, reduce drag, build airspeed, and it’s “Up, up, and away!” The simplest airplanes—Aeronca Champs, say, or Cessna 120s—don’t offer a lot of ways to do it wrong. Add throttle and enough rudder to keep her pointed straight, push the nose down while retrimming, and wait for airspeed to return before letting the snout come up. Larger fixed-gear, fixed-pitch singles like Cherokees and 172s add the slight complication of timing initial flap retraction to avoid settling.

As the machines get more complicated and powerful, though, more things must be done, and the order matters. “Power, climb, flaps, gear” might be the mantra in an A36 Bonanza, but even a lightly loaded Piper Arrow won’t climb with 40 degrees of flaps (or the gear down; Arrow pilots, please raise it as soon as you stop descending instead of waiting for positive rate). A Cub isn’t likely to torque-roll on you, but the urgency of proper rudder coordination increases with horsepower. And the more horses, the stronger the pitching moment until nose-up trim is corrected—one reason we don’t recommend trimming to fly hands-off on final. (Better feel for the airplane is another.)