A lot of attention has been directed at the FAA’s new airman certification standards (ACS), which prescribe how practical tests are conducted. Last year, the FAA implemented ACS for the private pilot-airplane certificate and instrument-airplane rating. A chief difference between the ACS and its predecessor practical test standards (PTS) is expanded integration of risk management principles. Another involves how slow flight is performed (“Revising Slow Flight,” February 2017).

The new ACS for the instrument-airplane rating issued in June 2016 also prescribes the minimum content of an instrument proficiency check (IPC), as did its predecessor. Unlike the PTS, for each task pilots are required to perform during an IPC, the ACS requires the pilot to demonstrate specific knowledge and risk management proficiency. That’s a change from the ways IPCs were done before. Let’s explore how the new ACS envisions an IPC will be conducted.

Dissecting the IPC

All instrument-rated pilots should be familiar with FAR 61.57(c), which details recent-experience requirements for IFR operations. Without getting too deep into the nuances, it boils down to accomplishing and logging at least six instrument approaches, plus holding, and intercepting and tracking courses every six months. If a pilot doesn’t meet those requirements, he or she cannot exercise instrument privileges as PIC until either obtaining the required recent experience or completing the instrument proficiency check prescribed in FAR 61.57(d).

The FAA’s instrument currency regulations are supposed to provide assurance that pilots can operate safely in the national airspace system under IFR. Yet, like all FARs, they are mere minimums and provide no such assurance. As the sidebar on page 6 highlights, even the rules under which instrument approaches can be logged provide no guarantee that you’re good to go down to 200 and a half next time.

The IPC includes some critical IFR skills while omitting others. For example, the mandatory tasks on an IPC include holding procedures, recovery from unusual attitudes and instrument approach procedures, including precision, non-precision, missed and circling approaches, plus a partial-panel approach. Notably missing from this list is pre-flight planning, preparation, and procedures, compliance with ATC clearances, or departure, en route and arrival operations.

In other words, the IPC is heavy on maneuvers-based procedures and does not emphasize the necessary and practical tasks associated with executing a real-world IFR mission in the ATC system. In fact, an IPC can be accomplished without filing an IFR flight plan, flying in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC), talking to ATC, operating in dense airspace (i.e., Class A, B, C or D), or checking the weather and its associated risks (if flying only in the local area with a view-limiting device and safety pilot under visual flight rules).

Long-time readers may recall my data-driven article (“Analyzing Fatals,” March 2012) demonstrating that poor risk management is the leading root cause of fatal general aviation accidents. That is, the pilot failed to identify, assess and/or mitigate risks associated with the hazard or hazards precipitating the accident. This is just as true for accidents that take place in IMC as it is for accidents occurring in visual conditions.

How will the new requirement to demonstrate specific knowledge and risk management proficiency for each task on the IPC be implemented? One example involves circling approaches: The pilot will be required to identify, assess and mitigate risks associated with executing a circling approach at night or in marginal visibility, conditions proven to be hazardous in the real world of IFR operations. Taking this example one step further, the new ACS risk management standards will help pilots think more strategically about certain risks, such as the advisability of performing circling approaches under any but the most benign conditions.

Managing The Risk of IFR

Every year there are fatal IMC accidents, such as the following examples, where pilots failed to identify, assess and/or mitigate risks associated with planned or ongoing IFR flights:

– Pilots who are “legally” current under 61.57(c) have lost control of the aircraft because of task saturation or other conditions that created elevated risk.

– Pilots have lost control of high-performance aircraft due to vacuum pump failures that may have occurred under VMC conditions, yet they continued into IMC conditions.

– Pilots have attempted to penetrate known convective weather and suffered aircraft structural failure.

– Pilots continue to press on under conditions of fatigue, aircraft equipment failures, weather and other factors due to schedule or other (often self-imposed) pressures.

When is An Approach An Approach?

The FAA recently tried to clarify the byzantine method for “logging” an instrument approach procedure (IAP). Information for Operators (InFO) No. 15012 was issued on September 8, 2015, and specified the conditions under which an IAP counts for currency purposes. It’s beyond the scope of this article to get too deep into this subject, so I’ll summarize it below. The full text of this document [PDF] is available on the FAA’s web site.

According to this document, you can log IAPs in an aircraft in actual instrument flight conditions, in simulated conditions in an airplane using a view-limiting device (with a safety pilot), or in certain simulation devices (full flight simulators, flight training devices or aviation training devices).

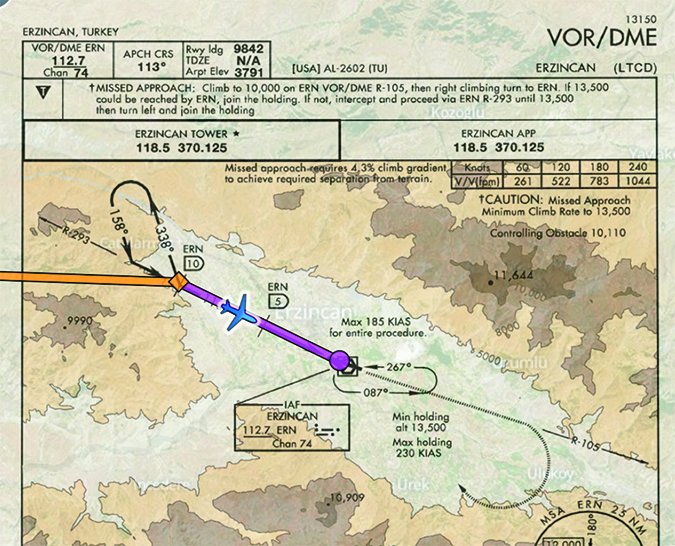

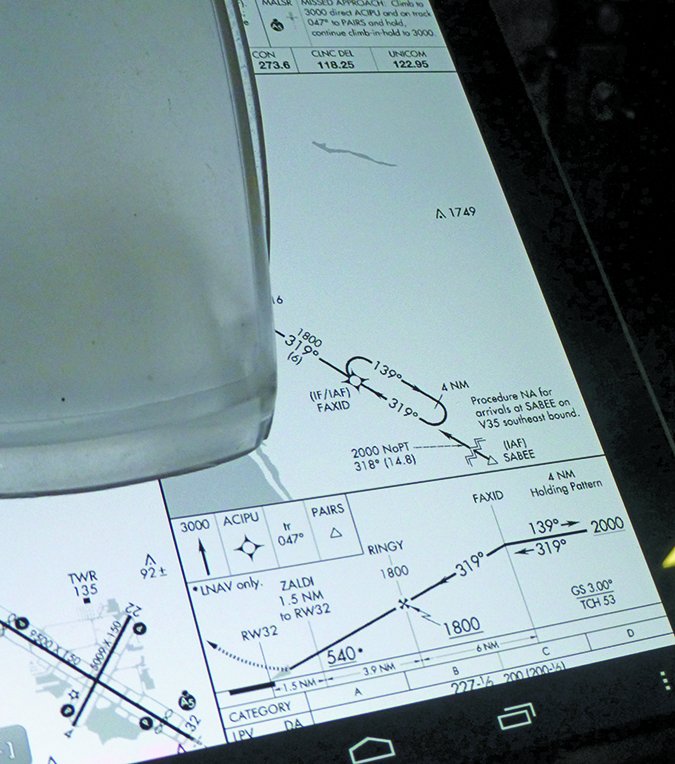

If you accomplish the IAPs in an airplane in actual conditions (my usual method), certain requirements apply. For example, you must be established on all required segments of each IAP (initial, intermediate and final approach segments, but curiously not the missed approach segment) if you fly the whole approach. However, if ATC is radar vectoring you to final, you need not fly the other segments. As I interpret it, you must be in actual IMC on each segment, although it doesn’t have to be continuous IMC.

Once you have established the aircraft on final and passed the final approach fix (FAF), it’s acceptable to break out into VMC conditions. The FAA doesn’t require you to be in IMC all the way to the decision height (DH) or minimum descent altitude (MDA).

So, how does this work in practice? In my case, in the Pacific Northwest, there are about six months of the year when overcast conditions frequently prevail, but the conditions often are 1500-2000 overcast with tops as low as 4000-5000. To take one example, if I depart Bellingham (KBLI) under IFR/IMC in these conditions to perform the RNAV (GPS) RWY 11 approach at Burlington Skagit Regional (KBVS), the total distance for the initial, intermediate and final approach segments to the final approach fix is about 19 nm. The crossing altitude at the FAF is 2200 feet. Assuming 2000 feet overcast and 5000-foot tops, I will probably be in clouds for a little less than 10 minutes. Yet, I’ve completed an approach that I can log as “actual” while the ceiling is 2000 feet.

Does any of this bother you? It should. If I were to follow this routine exclusively, I would be barely competent to operate in conditions that, while technically meeting the requirements, certainly do not ensure my competency under more severe IMC conditions. All too often, however, pilots may choose to just conduct the six required IAPs in a benign environment.

When you consider the above questions collectively, you may conclude that your overall instrument proficiency is such that you need to create more slack in your personal minimums for operating in IMC conditions. For example, you might want to add 500 feet to your approach minimums or avoid IMC flights at night. If you have enough self-mastery to do this, congratulations; you’re in good company.

Proficiency Scenarios

At this point, you’re probably wondering what kind of instrument proficiency program I’m advocating. In my view, it must be a program that comes as close as possible to replicating the real-world profile of the missions you usually fly. It should engage all elements of the SRM skill set and would be most effective under an IFR flight plan in actual IMC conditions. It should take place in a challenging ATC environment in congested airspace.

Using my own example, rather than just “shoot approaches” in the local area such as I described above, I normally create an “instrument proficiency scenario (IPS)” that looks more like a typical “mission” for my flying, such as visiting a potential client. Thus, I might periodically file for a destination in the Seattle Class B airspace area and try to pick a day when weather conditions are moderately challenging. Rather than the 2000-foot ceilings I earlier mentioned, I might seek a day when the ceilings are no higher than 800-1000 feet. Rather than my minimal performance in 2016, I’m aiming for at least one such “scenario” each month, on average.

How should instrument proficiency scenarios be conducted? If you choose the IPS rather than the IPC route to maintaining instrument proficiency, you have several options. In every case, you should design the scenarios around real-world typical flights and not just conduct repetitive IAPs. Providing you continuously comply with the instrument currency provisions of 61.57(c), you can fly these scenarios in actual IMC conditions without a safety pilot.

If you can’t find actual IMC, you’ll need to conduct the flight using a view limiting device and an appropriately qualified safety pilot. If none of the above applies, you can conduct the scenarios in the simulation device. Although simulation technology is rapidly improving, including the addition of ATC interaction, most devices available to general aviation pilots still do not provide the ideal environment for an IPS, in my opinion.

You can also conduct your IPS under the tutelage and guidance of an instrument flight instructor, either in the airplane or a simulation device and under actual or simulated instrument conditions in an airplane. This could, if you both so elect, meet all the requirements of an IPC. However, if you’ve maintained instrument currency under 61.57(c), then the IPC is not required. It might be more beneficial to skip the holding patterns and expose yourself to more typical instrument situations that you are likely to experience in your normal flying.

Last, but certainly not least, some members of the flight training community advocate receiving an IPC every six months, regardless of a pilot’s activity and proficiency level. While I agree that this is helpful, you should really consider your own situation to determine practical intervals for obtaining an IPC. If you have substantial experience, follow the guidelines above regarding maintaining SRM proficiency, conduct all your proficiency flights as IPSs and manage risk effectively, then I believe the interval for receiving an IPC can be safely extended. In the final analysis, you need to be the judge and manage your own instrument proficiency program.

What Matters Most

The real ability to master operating personal airplanes under IMC conditions often boils down to full proficiency in single-pilot resource management (SRM). These skills include risk management, automation management, task and workload management, and maintaining situational awareness (SA). Even though you have “logged” your approaches, holding, and course interceptions and tracking, you should ask yourself the following questions before determining if you’re proficient for the flight at hand and not just “legal.”

– Are you skilled at identifying, assessing and mitigating risk? If not, maybe you should take a risk management course.

– Can you operate the automation in your aircraft under all modes and operating conditions? If not, maybe it’s time to review the pilot operating manuals for your installed equipment.

– Can you handle the workload in your high-performance aircraft during all phases of flight without experiencing task saturation? If not, maybe it’s time to examine your personal cockpit flows and procedures.

– Do you use all available equipment and resources effectively to be aware of aircraft status, environmental conditions and threats, aircraft position and ATC requirements? If not, maybe you should re-examine your procedures for maintaining situational awareness.

Robert Wright is a former FAA executive and president of Wright Aviation Solutions LLC. He is also a 9600-hour ATP with four jet type ratings and holds a Flight Instructor Certificate. His opinions in this article do not necessarily represent those of clients or other organizations that he represents.