The overall reason we conduct a preflight inspection is to verify everything on the airplane is both present and working. We check fluids, tire and strut inflation, look for damage and wiggle things like ailerons and rudders to ensure they’re working as they should. Once we’re satisfied the airplane is ready to fly, we mount up and launch. But what if we find a piece of equipment that’s not working? Can we still fly?

The quick answer is it depends on the equipment that’s broken and the conditions of the planned flight. To help us make the correct determination, one that is both legal and safe, there are some regulations to follow and some paperwork to check. If the failed equipment isn’t required by regulation or the airplane’s documentation, it’s likely we can fly but we may need one more piece of paper to make it all legal.

The Regulations

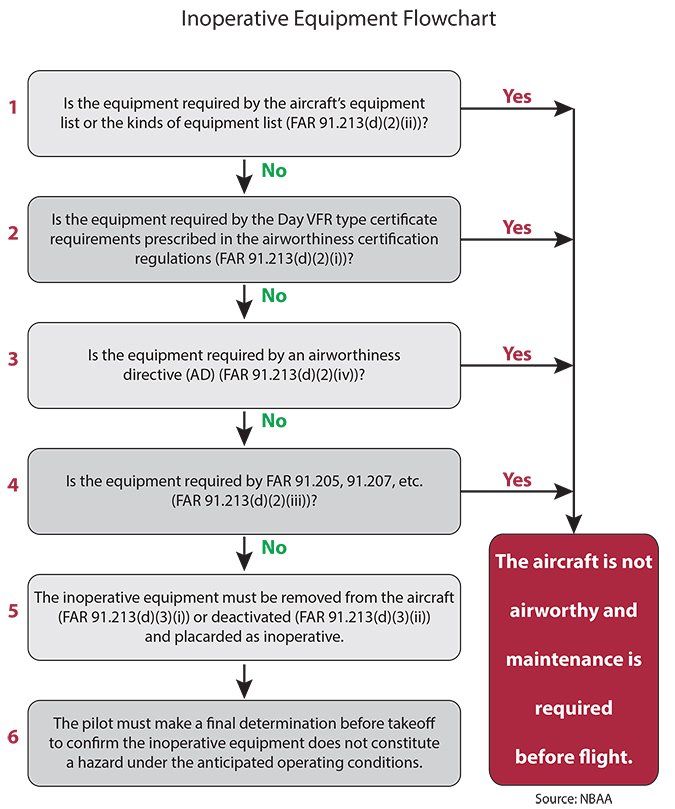

The flowchart on the opposite page describes the overall process for determining whether the airplane is airworthy despite failed equipment. There are three regulations you need to review when using it. The main regulation is FAR 91.213, helpfully titled “Inoperative instruments and equipment.”

The first portion of 91.213, subsections (a) through (c), deal with minimum equipment lists. If your aircraft has a minimum equipment list (MEL), it will be published among the rest of the aircraft’s paperwork, usually in the POH/AFM document. If an approved MEL exists for that aircraft and the other conditions of 91.213 (a) through (c) are met, you’re good to go. For most of us, however, no approved MEL exists, and we must refer to FAR 91.213(d). This is where it gets interesting.

To correctly determine the aircraft airworthiness under FAR 91.213(d), we must use the POH/AFM for that specific airplane and dive into the equipment list, usually found in the weight and balance section. This is detailed in box 1 of the flowchart on the opposite page.

The aircraft’s equipment list will list all the factory-approved required, standard and optional components available when it was manufactured. Some means will be included to denote whether certain equipment is required or optional. An example of required equipment might be an oil pressure gauge; a navigation light usually isn’t required for daytime VFR. If the failed equipment is required, you’re grounded until repairs can be made. It’s that simple.

On the other hand, if the equipment is optional, or not required for the anticipated flight conditions, box 2, you still may be good to go. In addition to a navigation light, pitot heat comes to mind as both an optional piece of equipment and not required under day VFR. You also need to refer to FARs 91.205, “Instrument and equipment requirements,” and 91.207, “Emergency locator transmitters,” as detailed in box 4, below.

The Paperwork

So, there are three principal FARs and the aircraft’s equipment list found in the POH/AFM we must consult before determining if we can fly with the inoperative equipment. What else?

Well, how about an applicable airworthiness directive (AD)? Of course, an applicable AD that hasn’t been complied with may itself ground the airplane. But an AD also can specify conditions under which failure of a specific component must be resolved before flight. Since an AD becomes part of the aircraft’s certification basis once it’s been issued, failure of any equipment required by it usually means we need repairs before flight. This is detailed in box 3, above.

While the aircraft’s equipment list may be both long and inscrutable, you may be distressed to learn you’re not finished. What about supplemental equipment that’s also part of the POH/AFM? An example could include a GPS navigator, a problem with which you may not discover until the engine is started and you’re loading a flight plan. The aircraft’s POH/AFM likely has a supplement in it regarding such equipment. If the equipment isn’t working as the supplement specifies—perhaps an annunciator’s indicating lights have failed—you may be grounded. At a minimum, you probably can’t use the GPS under IFR until the annunciator is repaired. This is when a close reading of the supplement is required, along with consideration of the anticipated flight conditions. Another close reading may be required by the operating specifications, if any, under which the flight is to be conducted. This primarily concerns flights intended to be conducted under FAR 121 or 135, but FAR 91 Subpart K also may come into play, as may some other document required by the FAA.

Finally, the failed equipment must be placarded as inoperative and disabled. According to the FAA, “The inoperative item shall be deactivated or removed and an INOPERATIVE placard placed near the appropriate switch, control, or indicator.” Deactivation may be as simple as pulling the equipment’s circuit breaker and putting a tie-wrap around it so it can’t be reset. If the equipment is removed, doing so usually requires a logbook entry since, at a minimum, the aircraft now has a new weight and balance, and equipment list. “In all cases,” say the FAA, “the item or equipment must be placarded INOPERATIVE.”

The Flight Conditions

If you’re launching in day VFR, you may not need that GPS navigator, anyway. You won’t need pitot heat, either, nor navigation lights or a clock. How about a radio, or a landing light? Typically, failure of one or more of these items will not ground you. As always, however, the FARs and the POH/AFM must be consulted to verify such an decision. For example, a failed landing light is only required a) at night and, b) when the flight meets the FAA’s definition of “for hire” (FAR 91.205(c)(4)).

What about the nav/comm? Well, it’s not likely a nav/comm is required by the POH/AFM’s equipment list, but if you’re planning on using a towered airport for your day VFR flight, you either need a working comm radio or must coordinate light gun signals with the tower. Whether you need a transponder also depends on where you intend to fly.

Things get more complicated—and more equipment is required—when flying at night and/or IFR. For example, the navigation lights may need to be working, as may the clock. What about the outside air temperature gauge (OAT) or the installed avionics’ electronic charting capability? Must you have a current database for your GPS navigator? What about the ADS-B In traffic and weather equipment for which you paid so dearly?

The OAT may or may not be required. There’s no FAR we can find that says we must have an operating OAT under IFR, but the electronic charting capability and the box’s navigation database may be required to work—and be updated with current data—under the relevant POH/AFM supplement if you plan to fly IFR and use it as the primary means of navigation.

The Decision

When faced with inoperative equipment, the pilot in command has a few decisions to make. As we’ve outlined, the first ones involve whether the aircraft is legally airworthy. If the FARs and the facts lead the PIC to conclude the aircraft is airworthy for the proposed flight, there still are some other decisions that need to be made.

First and foremost among them is whether the flight can safely be completed with the inoperative equipment. A failed backup artificial horizon is a great example. It may not be required by the FARs nor—probably—by the POH/AFM and its supplements, but launching without it into low IFR may not be the smartest thing. An inoperative heater aboard a piston twin likely isn’t required, either, but if you plan on cruising in the teens over North Dakota in February, you may wish to reconsider. Same with supplemental oxygen; you can remain below altitudes where it’s required, but if you’ll be flying at 10,000 feet, at night, for four hours, you’re increasing risk.

There’s no way the FAA can write a rule providing a clear-cut decision for every possible equipment failure. Nor should we want it to; there simply are too many variables. In addition to assessing what’s required by the FARs or the POH/AFM, we need to assess the extent to which, if any, we need optional equipment to complete the mission, or at least make it less risky and more comfortable. Once the regulatory requirements are fulfilled, the PIC needs to make the decision.

Jeb Burnside is this magazine’s Editor-In-Chief. He’s a 3200-hour instrument-rated ASEL/ASES/AMEL commercial pilot and aircraft owner.