We all know how to fly a missed approach. We probably did a handful of them on our instrument checkrides, and when we’re out practicing approaches, even in a sim, we most often go missed. We may not be flying a full missed approach procedure as published, but we still have to reconfigure the airplane and climb away. When we’re practicing, we know how the approach will terminate: by going around at the missed approach point. It’s what we expect when practicing.

When you prepare to fly a for-real instrument approach, part of your briefing is the missed approach procedure. Then you fly the approach, almost always breaking out well above minimums and landing. That’s what we’ve come to expect. But what if you get to the missed approach point (MAP) and do not have the runway environment in sight? Are you really ready to fly the missed approach procedure without having to refer back to the approach chart? How can you fly this critical maneuver precisely? What are your expectations?

Powering down

One of the keys to a good landing is a good approach. Similarly, the key to a good missed approach is to fly the final descent precisely to the missed approach point—it allows you to begin the missed from a known place at a known speed and in a known configuration. Holding glidepath or glideslope to the MAP is an exercise in energy management, and the most effective way to manage a glide path while flying a constant airspeed is to maintain the power necessary to fly a constant rate of descent.

If you fly a turbocharged piston airplane that automatically maintains a constant power setting with changes in altitude, adjust your throttle as needed at the FAF. From there, as you descend the power remains the same. If you fly a turbine with autothrottles, the system does it for you. Everyone else has some work to do. As you descend, the air pressure increases at the pressure lapse rate, about one inch of mercury per 1000 feet in the lower atmosphere. In other than turbocharged or autothrottle airplanes, this means the power will increase as you descend, about 1.5 inch or five percent in the typical 1500 vertical feet between the FAF and the MAP. This increase in power causes your rate of descent to decrease—uncorrected you will end up high on glidepath or, if you force the attitude down to keep the glideslope centered, you will speed up and become unstabilized, out of trim. Neither is desirable.

Instead, in an airplane in which power increases during descent, occasionally scan the engine gauges and adjust throttle to maintain a constant power setting. You don’t have to obsess about this; you only need to tweak the throttle one or twice during the descent phase of your approach. But make the adjustment to keep the power roughly constant, and you’re more likely to arrive at the MAP on-speed and on-glidepath—all the better to land, if conditions permit, or to miss.

500-Foot Window

Traditional instrument approaches without glideslopes generally have a minimum descent altitude (MDA) of about 500 feet agl. If no one had ever invented the glideslope, you could still land out of most instrument approaches. Put another way, if you can’t accurately fly the last 300 feet from MDA to the MAP, the glidepath doesn’t really help you at all (except, of course, when it comes to stabilizing your approach).

So instead of evaluating your approach at only one location, the missed approach point, consider success to be determined at two places: the MAP, and 500 feet agl on your way down. Are you on-speed, in the right configuration, and on-glidepath at 500 agl? If yes, or extremely close to yes so that you can smoothly correct in the time remaining, continue. If no, then begin the missed now, because you’ll only get dangerously unstabilized as you’re converging with the ground.

At 500 agl put your hand on the throttle(s). Make that last throttle adjustment to stay at your target power, adjusted very slightly if the glideslope is within a dot above or below the center. Further, as you reach the MAP, you’ll have to move the throttle one way or the other—aft toward idle, if you see the runway environment, or forward if you will continue the published procedure and fly the missed.

Missing, You

You’ve now begun the highest workload phase of an instrument approach—the missed approach. There’s a lot you have to do to transition from descent to a safe climbout. The standard missed approach assumes at least a 200 foot/nm climb gradient. The minimum rate of climb you’ll need to maintain this gradient depends on your groundspeed. The table below shows the climb rate necessary to meet that minimum, but not exceed it.

These climb rates are easily achievable for most IFR airplanes. But if your airplane is heavy, the density altitude is high, or you’re laboring with reduced engine power, you may have to decide before ever beginning an approach near minimums whether you’ll have the climb capability to miss the approach if needed. In fact, the minimums for many approaches in mountainous terrain are driven not by obstacle clearance requirements inbound to the airport, but the terrain or obstacle clearance necessary for the missed approach.

When you miss, ATC expects you to climb straight ahead to at least 400 feet agl before making any turns (higher, if the procedure specifies). At the minimum 200 foot per nautical mile climb rate, you’ll be over a mile from the point you initiate climb before you’re at 400 feet agl—in most cases still over the runway, or just beyond the departure end on shorter runways. Still, there’s a lot going on in the first the first 400 feet agl while climbing out from a gray hole. You need to manage transition time well to safely begin the missed.

A common element in instrument training—and likely a factor in many accidents—is what I call “missed approach denial.” Pilots are by their nature can-do people, and this sometimes manifests itself in an expectation that they will be successful in their flight operations. Consequently, they tend to expect to land out of every approach. Missed approach denial will cause indecisiveness and delay at the MAP when you have no time for either. We need to redefine “success” to be flying the procedure to FAA and personal standards (including the missed approach if needed). Landing doesn’t define success. Precision does.

Set-up for success

Missed approaches are riskiest when workload exceeds the pilot’s immediate capability. By reducing pilot workload, we can have a much greater margin of safety. If the runway is not in sight at the MAP, at the very least you need to:

• Advance power;

• Begin a climb, initially straight ahead;

• Configure the airplane for climb;

• Prepare to navigate the published procedure or that previously assigned by ATC; and

• Report the missed approach.

Let’s look at each of these requirements, and consider what can be done to reduce workload as much as possible.

Propeller(s): If you are flying piston or turboprop airplanes with multiple controls to advance power, set the propeller controls to the climb position before reaching the missed approach point. You have effectively made your airplane a single-engine control design; move the throttle(s) or power lever(s) to the climb position and propeller position is already set. Open the cowl flaps, if any.

Mixture: Many pilots fly at lean-of-peak (LOP) power settings. A mishap trend is emerging where LOP pilots have power failures at the beginning of a missed approach. If the mixture is very lean, advancing the throttle will cause it to go leaner still, reducing power. To minimize your workload, advance the mixture control to a well rich-of-peak setting before beginning your approach so there’s one less thing you need to do.

Climb straight ahead: Many missed approach procedures are quite complicated, but they all begin the same way: climb straight ahead to altitude before beginning turns. Keep the wings level as you smoothly add climb power, and keep the slip/skid ball centered.

Configure for climb: Once power is up and attitude is right, begin reconfiguring the airplane for climb. Some airplanes will demand you begin retracting flaps right away, especially at higher density altitudes. Others will climb just fine with some flaps out. Experience or instruction in the airplane you fly will teach what’s best for you. After you’re on attitude and speed and have a positive rate of climb, retract landing gear (as appropriate) and retract any remaining flaps as needed.

Navigate: Once we’re climbing in trim with the wings level, prepare to navigate the missed approach. Approved GPS navigation systems go into suspend mode so they don’t indicate a turn while you’re still below a charted minimum altitude. You may have to manually exit this mode to regain GPS navigation.

Report the miss: Lastly, tell ATC you missed the approach so they know you’re flying the miss procedure. This can (and must) wait until you have everything else under control. A lot of talking starts, usually followed by a frequency change, when you make the missed approach call, a distraction you don’t need in the initial moments. You were already cleared for a missed approach as part of your approach clearance, so fly what you were told to fly until you have everything else under control and are ready to deal with ATC.

The first 400 feet

The first moments of a missed approach offer the highest workload you’re likely to encounter as an instrument pilot. You’ve got a lot to do to turn a descent into a climb, and you’re very close to ground you cannot see. Successfully flying the transition into the missed approach is greatly enhanced by the proper mindset and preparation. When you reach the missed approach point and nothing is visible outside the windscreen, there are a minimum number of things you need to do to get the airplane pointed safely skyward.

Before the FAF

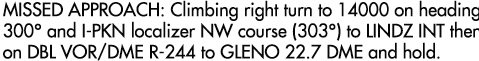

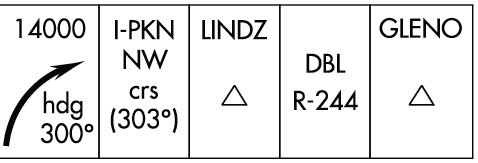

Before you pass the final approach fix (FAF) inbound, you should have three pieces of information immediately available to you without having to dig it out of a sometimes complicated instrument approach chart. Memorize them. Put them on a sticky note, or write them on your kneeboard: You need to know how low, how far and which way. That is to say, what is the lowest altitude you may fly for each segment of the approach from the FAF to the missed approach point (MAP); what determines the MAP, whether a waypoint, an altitude or old-fashioned approach timing; and most pertinent to this discussion, the headings and altitudes you’ll fly for the missed approach procedure.

Vertical Speed Required To Achieve A 200 Foot/NM Climb

Ground Speed (kts) | 90 | 100 | 120 | 140 |

Vertical Speed (fpm) | 300 | 417 | 500 | 583 |

The missed approach for the VOR/DME C procedure at Colorado’s Aspen-Pitkin County/Sardy Field (KASE) requires having a lot of information at your fingertips.

Autopilots and the missed approach

It’s common practice to fly autopilot-coupled approaches in low IFR conditions. There’s a very strong argument that this increases safety significantly by keeping the airplane within very tight instrument tolerances all the way to the missed approach point, and enabling the pilot to maintain the “big picture” while monitoring the autopilot-flown approach.

But everything changes if the runway environment is not in sight at the MAP. Most general aviation autopilots are not capable of transitioning from a coupled approach to a missed approach. At the MAP you must disengage the autopilot and hand-fly into the climb. Once established in climb, you can reengage the autopilot if you wish. (See the sidebar on the opposite page for some thoughts on managing the autopilot during the miss.) The newest generation of autopilot can fly the transition fully coupled at the touch of a “go-around” button. This is not without its own hazard, however; engaging the go-around mode puts the airplane into a climb attitude, but unless you simultaneously advance power to climb and promptly clean up the airframe, the angle of attack may become critical.

Meanwhile, many only slightly older autopilots have a go-around button that disengages the autopilot and moves the flight director command bars to a straight-ahead climb attitude. You have to do everything by hand; the flight director merely gives you a precise target to fly to. So be familiar with this system, too.

Further, autopilots have the ability to hold a little control force against trim. This is why it’s common for an airplane to pitch up or down when you click off the autopilot—the system was “pushing” or “pulling” against the trim. When you reach the MAP on a coupled approach, then, not only may you have to take over manually and hand-fly at least the transition into climb, but you may have to do it with a slightly out-of-trim airplane. Anticipate the possibility the nose will want to go up or down from its desired pitch when you click off the autopilot to begin the missed.

One more time, this means you need to be intimately familiar with the system in the specific airplane you are about to fly, because they may operate very differently.

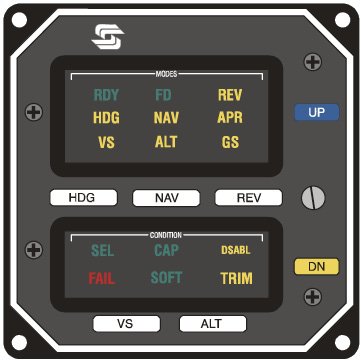

Missing With George

• Before engaging altitude hold, or selecting a climb or descent, the unit likely must be operating in either heading or navigation mode, with either the proper heading selected or the nav source configured.

• Before engaging vertical speed mode, the climb rate must be selected. Usually, it’s set to the descent rate selected earlier, while maneuvering for the approach.

• Also needed is the top altitude, the one to which we want to climb.

All this involves a lot of what I call “monkey-motion” at a critical time, and might best be left until the airplane is properly configured for the miss, a positive climb rate is established and there’s some air under you to provide a margin for error. —J.B.

Tom Turner is a CFII-MEI who frequently writes and lectures on aviation safety.