When I got my private at age 18, I was flying a Cessna 152 off a pasture. It didn’t take much to memorize the steps necessary to get the old girl started: I followed the old adage, “Kick the tires and light the fires.” When the checklist said, “Gas on fullest tank,” it was pretty easy, since the 152’s fuel selector is an on/off affair and always draws from both tanks. In my 18-year-old brain, the checklist seemed like an unnecessary list of the obvious. It either directed me to change the airplane’s configuration to what it already was in or change it to one that was patently obvious given the stage of flight. In short, my early experiences did not help me build the best of habits.

After a 20-plus-year hiatus, I returned to flying, and this time the checklist started making a lot more sense. My return to service as a rusty pilot gave me a chance to establish habits that never fully took hold the first time around. Since I was relying on a rental fleet, each time I flew, it was with healthy skepticism: You presume the last person to fly the plane assuredly did something to its configuration that might kill you. I learned pretty quickly what to look for: Leaving the fuel selector on the “wrong” tank or turned off, or leaving the pitch trim positioned to guarantee a takeoff accident. The checklist became my insurance policy that I would catch all the things that could lead to a very bad day. Of course, it helped that I was no longer 18—the reasoning behind the checklist was more clear.

Why Do We Use Checklists?

The simple answer to why we use checklists is that humans are forgetful and aircraft systems are complex. The formal use of printed checklists in aviation purportedly began after the crash of a Boeing B-17 prototype, when a critical task was forgotten. Pilots realized there were simply too many things to remember, and even sharp people lose track when they become task-saturated. We humans tend to make mistakes due to forgetfulness and a propensity for distraction. Add stresses, and pressures, and humans become predictably unreliable. There is no simple metric for human error rates, but it is reasonable to assume as high as a 10-percent error rate for general everyday activities.

David J. Smith, author of Reliability, Maintainability and Risk, an influential engineering text often used to teach human factors, compiled a table of average human error rates in average tasks. According to Smith, we humans will make the wrong selection at a vending machine two out of every 100 times. We will accidentally boil milk one out of every 100 times we heat it. We will overfill a bathtub once every 100,000 times we use one. Luckily, we humans tend to up our game and reduce our errors when performing tasks that are more consequential than boiling milk, but when the list of critical items is longer than a handful, we are at greater risk.

Smith found that human error rates drop as we move from a complicated non-routine task (one error in 10), to a routine task with care needed (one error in 100), to a routine simple task (one error in 1000), to the simplest possible task (one error in 10,000). You can see that even though error rates vary for human tasks, the level of complexity or whether or not they are routine, both have an effect on the probabilities.

He noted there also are basic errors intrinsically related to human-machine interface. For example, we will enter a 10-digit number into a keypad incorrectly six out of every 100 times. If nothing else, that’s an error rate that should make any pilot sit up and take notice. The same error rate applies to reading digital or analog. No matter how diligently we scan a gauge, we will get the data wrong a certain portion of the time.

Enter the Checklist

The primary purpose of a cockpit checklist is to ensure we properly configure the aircraft for the phase of flight. That’s why checklists are broken down into the critical segments—takeoff, approach and landing—posing the greatest risk for an accident. Even though these segments comprise a small proportion of any given flight, they historically account for a majority of all hull-loss accidents.

By simplifying a task and reducing it to an item on a checklist, we can reduce human failure rates. Using a checklist helps us fly an unfamiliar plane, provided the checklist has all the critical items. Checklists help us remember things we may be too stressed or distracted at the time to remember. It is a simple acknowledgment and acceptance of the limitations of human performance.

All of us, even the most disciplined and exacting, are fallible and prone to errors. Since errors in flying are unacceptable, a checklist is a backstop to single-pilot operations and if we have a second-in-command, their job is to challenge the pilot flying with the checklist to ensure all critical items are completed.

I also look at the checklist as basic kill-proofing. When I flew rental planes, I relied on the checklist to keep other people from leaving gust locks in, ensuring fuel was on, etc. Now that I’m flying Part 135 in multiple, more complex aircraft, checklist items include making sure boost pumps are on and the gear is down. Why do I need the checklist? Not all planes have the same procedures and straying from the checklist for a particular aircraft runs the risk of conflating steps. For one plane I fly, turning the boost pumps on at a particular stage of flight will likely kill the engine by flooding it; for another, it is needed just to provide backup.

For all of us who fly retractables, the checklist is the one thing you know stands between you and being the person with a gear up.

Respecting the Checklist

The best checklists are built by and for pilots. The worst ones are built by lawyers and paint-by-numbers procedurists who are more interested in CYA than proper aircraft configuration. To me, the very best checklists are the ones we build for ourselves. We know which items are safety-critical, both for the particular aircraft we fly and the particular modes of failure we are prone to.

My philosophy is to always include things I have screwed up on in the past and to exclude things that don’t particularly add to flight safety. I also think checklists should align with a logical flow pattern.

Some pilots will argue that all configuration items should be on the checklist. Others will argue only the most critical items should be there. Every checklist tends to reflect one or the other philosophy. When you build and maintain your own checklist, you will own what is on it as well as the rationale for either leaving an item on or taking it off.

What item is on every checklist of mine? Cowl flaps — I have departed with cowl flaps closed and caught it when the CHT told me I was over my 380-degree target. For this reason I have added them to my shutdown checklist and to my pre-start list. They’re also a pre-taxi item and a pre-runway item. Look, I have forgotten cowl flaps in the past and while I don’t think of them as a much of a flight-safety item, using them will save me expensive repairs. By putting them on the checklist, I am drawing a line that says, “Never again.”

If you decide to customize your own checklist, it should be a reflection of who you are and an aspiration for who you want to be. Your checklist can be an itemized list of everything that must be done, literally a step-by-step procedure you use to configure and verify. This makes a lot of sense if you are learning a plane. Building this checklist helps you learn all the steps. This approach, however, results in a very long and very detailed checklist, the exact kind that gets blown off because it is too detailed.

For me, a checklist is an idiot check to cross-check my work after doing a flow pattern to get the airplane in the correct configuration. When I am still learning the plane and its specific procedures, I do find that it catches many items I miss. When I am getting to know a plane, I kind of like the longer list; after many hours in the plane, I tend to like the abbreviated lists better.

It doesn’t matter which philosophy you adopt as long as you adhere to some form of checklist discipline. My youthful bad checklist habit stemmed from flying the same very simple plane over and over. When I returned to flying using a rental fleet, my checklist habits improved. Then I finally bought my own plane and the more I got to know it, the less reliant on checklists I became. When I caught myself missing key items due to the return of my bad habits, I decided it was time to build my own custom checklist that captured my own rhythm of flying as well as the mistakes I was prone to make.

Seven Set And Check

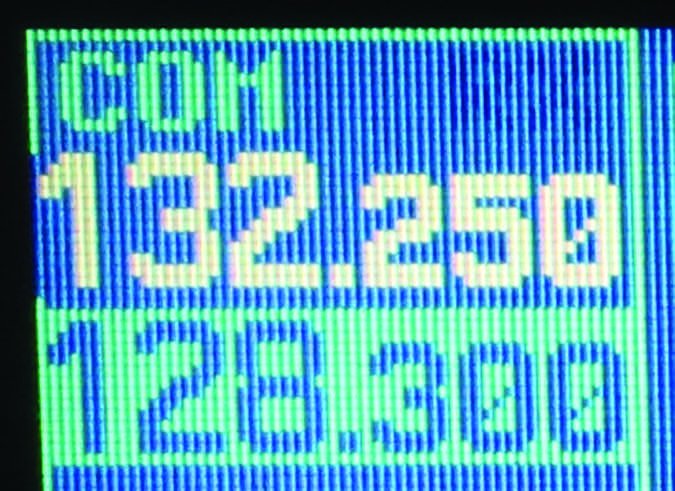

Most of us fly in the modern world with lots of radios, gadgets, nav aids, etc. The time to set that stuff is while you are on the ground. My new boss at GemAir in Salmon, Idaho, introduced me to “Seven Set and Check,” which you do before you leave the run-up area.

Chances are you have at least seven items. If you have dual flip-flop nav/coms, you can set the four com frequencies and their respective standby frequencies. You also might have at least one HSI, heading bug, or perhaps a CDI that could be placed into a setting that isn’t just the random number it was on when you got in the plane. Finally you have a transponder and compass to set. Basically, you should be able to set at least seven radio frequencies, heading bugs, CDIs or other navigation things with the brakes on. If you can’t, you are likely in a Cub or a hang glider.

What Where Once Checklist Items Are Now Habits

One last habit that backstops the checklist is the simple mnemonic used to backup the checklist. By now, we all have likely heard of CIGARS, or maybe the modification I use, CIGARTTIPSS. If your checklist blew out of the cockpit or you are the flight instructor and your student has the checklist, some preflight mnemonics are your last great hope for idiot-proofing. CIGARTTIPSS is the one I use. It stands for:

Controls (free and correct);

Instruments (in the green and set);

Gas (you have enough and set in the right configuration for takeoff);

Attitude (trim set for takeoff);

Runup (complete and you aren’t lying to yourself about anything that might have been dubious);

Transponder and Time (you’ve got to put the transponder on at some point and while you are on a T, note your departure time, start your timer or set your recording app to start recording the flight;

Instruments (still in the green, right? Altimeter set?);

Props (full forward, for us constant-speed prop folks); and finally,

Seatbelts and Switches (This is a good time and kind of your “last call” if you aren’t in the habit of buckling up or checking your passengers, and if you need to put on a boost pump, turn on your landing light, or switch fuel tanks.)

The more I find myself in different planes with different checklists, the more I like CIGARTTIPSS as my last task before taking the runway.

Getting it together

Any time you move from plane to plane, or move from flying simple planes to those that are more complex, you have to have a plan, more than a little discipline and good backup. The first step is to be honest about your own fallibilities and acknowledge human failure rates are inevitable. The sensible thing to do is use checklists, if possible, building your own to match your specific limitations, and then backstop them with other available tools. There’s no point in boiling your milk if you don’t have to.

Mike Hart is an Idaho-based flight instructor and proud owner of a 1946 Piper J-3 Cub and a Cessna 180. He also is the Idaho liaison to the Recreational Aviation Foundation.