When FAA Administrator Michael Huerta told attendees at the agency’s October 24, 2017, General Aviation Summit “it looks like 2017 will end up being our safest year yet,” he also took something of a victory lap. As Huerta’s five-year term nears its end in January, he and his team are taking some credit for what everyone hopes will be a distinct improvement in aviation safety. And since the airline accident rate essentially is zero, that means identifying real safety improvements in general aviation.

Huerta’s victory lap isn’t without merit. Under his management, the FAA has taken a number of steps—including ADS-B implementation, streamlining the approval process for non-required safety enhancing equipment and completing its rewrite of Part 23’s aircraft certification rules—designed at least in part to help reduce GA’s accident rate. While some preliminary numbers comparing 2017’s accidents and activity should be available from either the NTSB or FAA in a few weeks, it’ll be long after Huerta leaves the agency before the final, official numbers are in.

One of the key measurements by which reduced GA accident rates can be attributed to the FAA’s focus won’t be available for some time, however. That will be up to the NTSB, which determines an accident’s probable cause, and if any reduction in GA’s fatal accident rate is attributed to fewer loss of control events, then the agency—and the industry—can legitimately claim a win. That’s thanks to its multi-year efforts to identify in-flight loss-of-control accidents (LOC-I) as a leading cause of GA fatalities and minimize them.

FAA Updates Chart User Guide, Adds ‘What’s New’ Section

One FAA reference that should be on every pilot’s bookshelf—whether physical or electronic—is the Aeronautical Chart User’s Guide. As its title implies, the 131-page publication is the go-to resource for describing and explaining all the different symbols, typography and shading used on the FAA’s aeronautical charts, including sectionals, IFR high- and low-altitude en route charts, or approach plates. The Guide’s most recent edition, dated October 12, 2017, now includes a section highlighting what’s been added since the last edition (something it probably should have had all along).

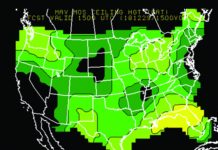

According to the latest edition, the “What’s New” section will highlight new charting symbology and other changes to charts.” The new edition includes the Caribbean VFR Aeronautical Charts (CAC-1 and CAC-2, an example of which is at right), which were first published in 2016 and replace the discontinued World Aeronautical Charts (WACs) as well as several other charting and symbology changes.

To learn more about the Guide and download a copy, visit tinyurl.com/AVSAFE-ACUG.

Are Circling Approaches Still Necessary?

The FAA is considering canceling certain published instrument approaches that terminate in a circling maneuver, include circling-only procedures and those with published circling minima. The word comes from an October 6, 2017, statement of proposed policy and request for comment. According to the FAA’s statement, the agency is proposing specific criteria to help it identify and select circling procedures that can be considered for cancellation.

The FAA is proposing that each instrument approach procedure (IAP) that includes a circle-to-land maneuver be evaluated by asking the following questions:

• Is this the only IAP at the airport?

• Is this procedure a designated MON (FAA’s VOR minimum operating network) initiative airport procedure?

• If multiple IAPs serve a single runway end, is this the lowest circling minima for that runway? Note: If the RNAV circling minima is not the lowest, but is within 50 feet of the lowest, the FAA would give the RNAV preference.

• Would cancellation result in the removal of circling minima from all conventional (e.g., terrestrial navigational aid-based) procedures at the airport? (Preference would be to retain ILS circling minima.)

• Would cancellation result in all circling minima being removed from all airports within 20 nm?

• Will removal eliminate the lowest landing minima to an individual runway?

Questions applied to those IAPs lacking straight-in minima (i.e., which are only circle-to-land approaches) include:

• Does this circling-only procedure exist because of high terrain or an obstacle that makes a straight-in procedure unfeasible or that would result in the straight-in minimums being higher than the circling minima?

• Is this circling-only procedure (1) at an airport where not all runway ends have a straight-in IAP, and (2) does it have a Final Approach Course not aligned within 45 degrees of a runway that has a straight-in IAP?

According to the FAA, “[a]s new technology facilitates the introduction of area navigation (RNAV) instrument approach procedures over the past decade, the number of procedures available in the National Airspace System has nearly doubled. The complexity and cost to the [FAA] of maintaining the instrument flight procedures inventory while expanding the new RNAV capability is not sustainable.”

The FAA published its proposed policy on October 6, 2017, as our previous issue was being finalized, and called for only a 30-day comment period, which was to end November 6, well before this issue appears in your mailbox. However, the agency says it will consider public comments on individual proposals to cancel specific circling procedures.

Intersection Departure Risks

In late October, the NTSB published Safety Alert 071-17, to highlight the increased risks posed by intersection takeoffs. The Safety Board urged general aviation pilots to use all the runway available to them for takeoff. According to the Safety Alert, “If an aircraft experiences a problem while conducting an intersection takeoff, the available runway remaining to abort the takeoff or perform an emergency landing is reduced or eliminated, resulting in greater risk of injury or aircraft damage.” The NTSB’s recommendations include the following:

– Allow adequate time for preflight preparations and taxiing to eliminate time pressure to conduct an intersection takeoff.

– Do your homework. Know your aircraft’s takeoff and landing performance limitations based on gross weight, density altitude and other considerations in the event of a malfunction that would require an aborted takeoff or emergency landing.

– Communicate the plan. Ensure your pretakeoff briefing to yourself and/or your crew addresses potential emergency situations.

– If you do perform an intersection takeoff, clearly communicate your intentions, your position and planned departure via local air traffic control procedures (CTAF) to alert potential conflicting traffic.

– Do not feel obligated to accept an intersection takeoff if it is offered to you by air traffic control.

– For most takeoffs, use all available runway length to increase your margin of safety. Recognize that using anything less than the full length of the runway is accepting a higher level of risk.

– In the event you need to return to the airport or runway, remember that an aerodynamic stall can occur at any airspeed, at any attitude and with any engine power setting.

Runway Status Light System (RWSL) Reminder

A recent Safety Alert for Operators (SAFO) from the FAA serves as a reminder about the automated system slated for installation at 20 U.S. airports by the end of 2017. According to the SAFO, RWSLs integrate “airport lighting equipment with approach and surface surveillance radar systems to provide aircraft and vehicle crews a visual signal indicating when it is unsafe to enter/cross or begin/continue takeoff on the runway.”

The SAFO (17011, September 29, 2017) goes on to note there “have been several instances at RWSL airports where flightcrews have ignored the illuminated red in-pavement RWSL lights when issued a clearance by Air Traffic Control (ATC). Illuminated RWSLs mean aircraft/vehicles stop or remain stopped and contact ATC for further direction, relaying to ATC that the RWSLs are illuminated.”

The FAA wants pilots and crews to know the RWSL is an automated system operating independently from ATC. Controllers do not have any indication of when the RWSL lights are illuminated, according to the agency. But they’re for real, and “failure to comply with illuminated red in-pavement RWSL lights may result in a high risk collision Runway Incursion event.”

It’s also important to understand the RWSL system is not a substitute for an ATC clearance, especially one to taxi onto an active runway. An explicit clearance to enter, cross or take off from a runway still must be issued by ATC at towered airports (you won’t find the RWSL at non-towered airports).

Although the RWSL system has been around a while, the FAA has a series of dedicated pages on its web site to pilots and other curious about what it is an how it works. The images at the bottom of this page showing how an RWSL installation will appear when activated are part of the FAA’s education and outreach efforts. Visit the site at www.faa.gov/air_traffic/technology/rwsl.

By the end of 2017, the RWSL system is supposed to be up and running at 20 major airports in the U.S. Upon encountering an activated RWSL system, pilot and vehicle operators should hold short of the runway and advise ATC they are “holding for red lights.”