There are many old sayings sprinkled throughout aviation. One of them, “There’s no such thing as an emergency takeoff,” highlights the fact that deciding to initiate a flight is optional. As pilots, we get to decide many elements of our takeoffs, including whether to perform one in the first place. This is important since there are many unknowns in the first few minutes after a takeoff.

One of the more important considerations we face when deciding to take off is the weather we’ll encounter. On a calm, sunny day, takeoff weather probably isn’t much of a concern, provided density altitude is reasonable for the runway and the airplane. At the other extreme, when the visibility is so poor we have trouble finding the runway, it becomes a different proposition. And in gusty conditions, like those associated with thunderstorms or passing fronts, takeoffs can be downright sporty.

Managing our takeoffs, though, is really about managing the overall flight and the risks it poses. For example, I’ve been known to delay taking off for a day to allow en route weather to either blow itself out or move away. Departing early in the morning often eliminates the risk of afternoon thunderstorms. And taking off with plenty of time to reach your destination before sundown eliminates the potential risks of flying over mountains at night.

Another old saying, which isn’t peculiar to aviation, is, “Timing is everything.” It’s especially true when nearby weather pushes us to take off before it arrives, and we’ve all probably seen a pilot rush through the preflight, crank up and taxi to the runway at the speed of heat, and take off without a run-up. While he (and it’s usually a he) may know something we don’t, it’s clear that better planning and a tactical delay often can help perfect our weather-avoidance strategies. Here’s an example of why.

Background

On May 29, 2015, at about 2115 Central time, a Beechcraft A36 Bonanza impacted terrain shortly after takeoff from Hale County Airport in Plainview, Texas. The pilot and two passengers were fatally injured, and the airplane was destroyed. Night visual conditions existed; an IFR flight plan had been filed. The flight was destined for Boerne, Texas.

Several witnesses reported seeing the airplane take off to the southwest, make a sharp left turn and then head straight down. One of the witnesses “could not believe anybody would take off in the approaching storm.” Another witness reported “watching the storm clouds” and heard an engine at “full throttle” and then looked over and saw the airplane “traveling very fast” toward the ground.

A handheld GPS was retrieved from the accident site; its stored data revealed the airplane departed from Runway 22 at about 2119, banked left and climbed to about 80 feet agl, reaching a groundspeed of 86 knots. The recording stopped less than a minute later.

Bad Timing

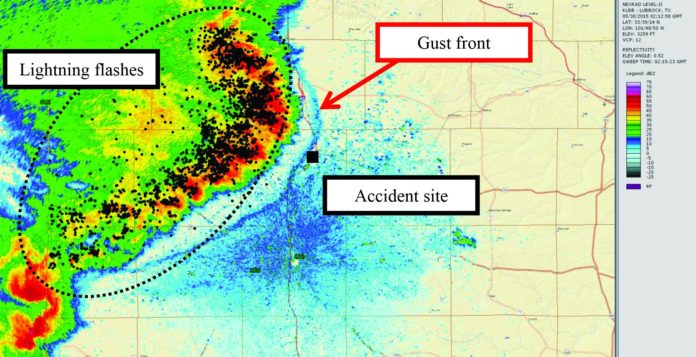

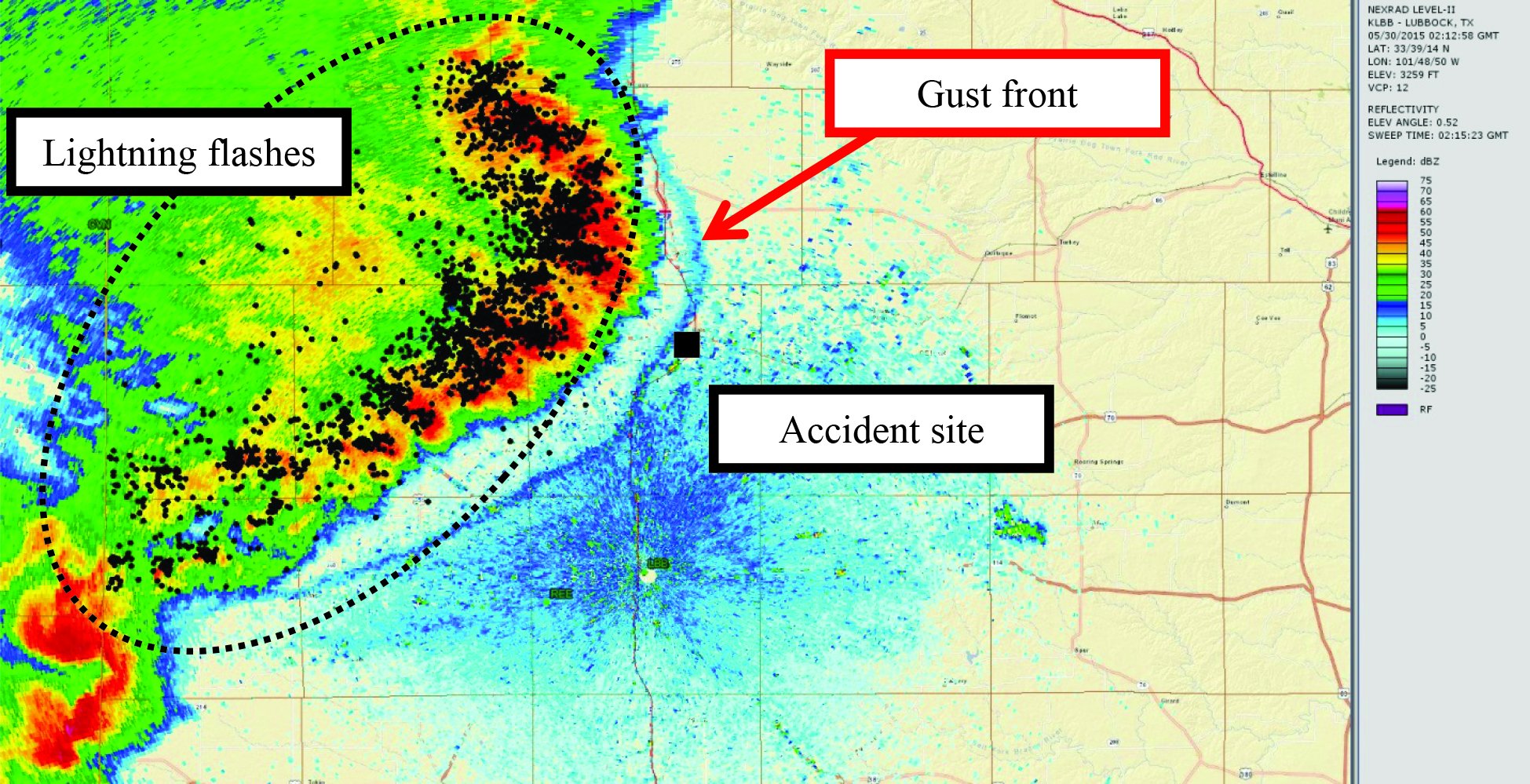

The image above, from the NTSB’s final report on this accident, depicts the observed weather radar data at about the time of the accident. Similar data from three minutes later depicts the gust front had moved past the accident site, the departure airport.

Not shown is the National Weather Service’s area forecast discussion, which stated, “Storms currently moving out of Northeast New Mexico will likely impact [the departure airport] later this evening…. Visibilities and gusty outflow winds will be the primary threats….”

Investigation

Earlier, at 2058:58, the pilot used ForeFlight to file his IFR flight plan and obtain weather information. A severe thunderstorm warning that included the accident site was issued at 2048. Another severe thunderstorm warning, valid for the accident site at the accident time, was issued at 2113, about six minutes before the takeoff attempt. The severe thunderstorm warnings reported 60 mph wind gusts and hail.

The 2055 automated weather observation at the departure airport included wind from 100 degrees at four knots with 10 miles of visibility under clear skies. Distant lightning (defined as beyond 10 miles but less than 30 miles) also was reported. Calm winds were observed at 2115, four minutes before the takeoff. By 2135, however, local conditions included winds from 300 degrees at 26 knots, gusting to 36 knots, 10 miles of visibility, light rain and scattered clouds layered at 4500 feet and 6000 feet agl, with a broken ceiling at 6500 feet. The sun set at 2051, and civil twilight ended at 2119. The approaching storm was visible to witnesses.

The airplane impacted terrain well within the airport’s boundaries in about a 20-degree-nose-down attitude. Ground scars were consistent with a near-vertical impact and extended landing gear. The wreckage path was about 162 feet long. A post-impact fire consumed major portions of the fuselage, empennage and wings.

The engine sustained extensive thermal damage in the fire. Its crankshaft was rotated by hand, and continuity was established between the crankshaft, camshaft, connecting rods and associated components. All cylinders were examined with a borescope; no anomalies were noted and each one produced compression. Both magnetos produced spark at all six posts when tested, and all spark plugs displayed normal wear.

There was no evidence of mechanical malfunctions or failures that would have precluded normal operation. All propeller blades displayed leading-edge polishing, chordwise scratches, leading-edge gouging and twisting deformation consistent with being under power at impact.

| AIRCRAFT PROFILE: Beechcraft Model A36 Bonanza | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Engine | Continental IO-520-BB | Standard Fuel Capacity | 74 gal. |

| Empty Weight | 2195 lbs. | Service Ceiling | 16,600 feet |

| Max Gross TO Weight | 3600 lbs | Range | 697 nm |

| Typical Cruise Speed | 168 KTAS | Vso | 52 KIAS |

Probable Cause

The NTSB determined the probable cause(s) of this accident to include: “The pilot’s decision to take off ahead of an approaching severe thunderstorm, which resulted in an encounter with hazardous weather conditions that led to a loss of airplane control.”

According to the NTSB’s research, “a gust front associated with a squall line of an approaching severe thunderstorm was over the airport at the time of the accident.” The storm likely produced strong gusting winds, turbulence, low-level wind shear, heavy rain, hail and lightning. “The flight encountered these hazardous conditions during initial climb [which] resulted in his loss of airplane control shortly after takeoff…. The pilot’s decision to take off with such hazardous weather conditions present resulted in the accident.”

According to the NTSB, there is no record of the accident pilot receiving or retrieving any weather information other than the ForeFlight briefing he obtained at 2058, 21 minutes before the attempted takeoff. That briefing included the severe thunderstorm warning issued at 2048, which specifically mentioned Plainview, Texas.

Given the relatively short amount of time between the ForeFlight briefing and takeoff, the pilot may not have had time to review it before completing his preflight inspection, loading two passengers, starting up and taxiing to the runway. Then again, maybe he did see the warning, as well as related radar data, and decided to get out before the storm arrived. He chose poorly.