Regardless of what you fly, how it’s equipped, and how old or new it is, you eventually will encounter inoperative instruments and/or equipment during a preflight inspection. It can be something known to the operator and the maintenance department, or it can be something new. Once the inoperative component is discovered, you have to make a determination whether it’s legal to fly the airplane without repairs, and then decide if it’s safe to fly. The two are not the same.

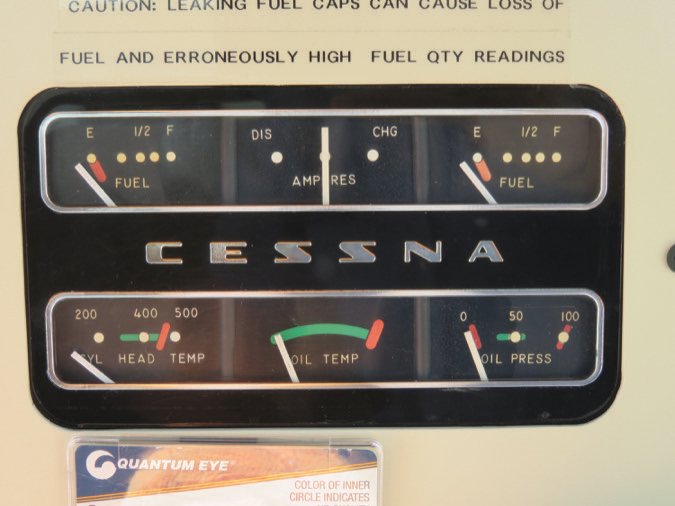

The good news is you have some guidance in FARs 91.205 and 91.213, and you also may have a minimum equipment list (MEL) to help determine what is and is not required to be operational on your planned flight. And the aircraft’s type certificate data sheet (TCDS), plus any applicable airworthiness directives (ADs), also may need to be factored into your decision, as well as any supplemental type certificates (STCs). Needless to say, you need more operating equipment for a day VFR jaunt around the pattern than you need at night or under IFR.

Background

Years ago, the rule on inoperative instruments and equipment for small aircraft was simple: If it was installed, it had to work or you could not take off. Aircraft in common use at the time were minimally equipped with no electrical system, no gyroscopic instruments and no radio equipment, so the policy of everything had to work was somewhat more appropriate than it would be today. Essentially, there was so little equipment or instrumentation aboard the then-modern aircraft, if something broke, it likely was a critical, required component.

As modern aircraft with electrical systems, gyroscopic instruments and avionics came into common use, the policy had to change. The FAA eventually recognized this and updated its regulations to reflect that there are many items that could be inoperative yet not make the aircraft unsafe to operate.

Additional revisions were made over time and eventually included MELs—formerly a province of large and transport aircraft—for small general aviation aircraft. An MEL likely isn’t something you need to go out and obtain for your flivver, as we’ll see in a moment.

What The Regs Say

Where does one find what is required? One place to begin is FAR 91.205. It starts with a basic listing for daytime VFR and then adds requirements for night and IFR operations. Meanwhile, FAR 91.213 lists additional requirements, including those “indicated as required on the aircraft’s equipment list or on the Kinds of Operations Equipment List for the kind of flight operation being conducted.” This FAR also introduces the MEL concept and provides basic guidance on how to use one.

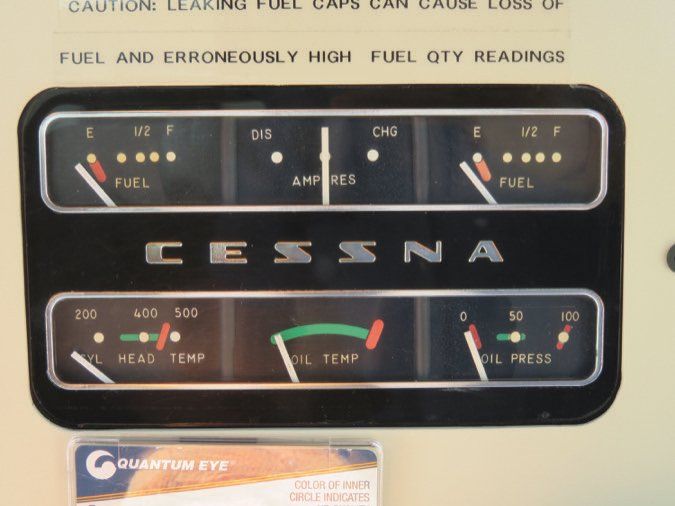

As these regs reference, there also can be requirements spelled out in the aircraft’s TCDS, such as oleo strut fairings on certain Piper Cherokees or a stall warning horn for a particular Cessna. See the sidebar above for details on which resources you may need or want to consult.

Over the years, FAR 91.213 has been revised and now includes three paragraphs dedicated to MELs. Paragraph (d) states that “except for operations conducted in accordance with (a) or (c) of this section, a person may takeoff an aircraft in operations conducted under this part with inoperative instruments and equipment without an approved Minimum Equipment List.” The takeaway here is that if you elect to implement an MEL program approved by the FAA for your particular aircraft, then you must always abide by the provisions of the MEL until it is canceled. You may not switch between paragraph (d) and an MEL if one has been approved for your aircraft.

Paragraph (d) also states that small aircraft are allowed to take off with inoperative instruments and equipment provided that they are not required. This is where it can get sticky in determining just what is required. Looking at this from different angles may convince you to reconsider the use of an MEL rather than have to do the research to determine if in fact an instrument or equipment item is necessary for the safe operation of the aircraft. An MEL approved for a specific aircraft should encompass research into all areas that may require an instrument or item to be operational before takeoff. This would allow you to go to the specific section covering the item in question and abide by the specific details. If the item is not listed in the MEL (i.e., a magnetic compass, which is required for all operations by FAR 91.205), then the item is necessary.

Looking further, paragraph (d)(3)(i) allows operation of small and non-turbine airplanes, among other aircraft types, if the inoperative instruments and/or equipment are removed from the aircraft, the cockpit control placarded and a record made in the aircraft’s maintenance documentation. “An aircraft with inoperative instruments or equipment as provided in paragraph (d) of this section is considered to be in a properly altered condition acceptable to the Administrator.” Under a different FAR, 91.405, the inoperative instruments or equipment is to be repaired, replaced or removed at the next required inspection.

To MEL Or Not MEL

While it may seem for most operators of small single-engine aircraft that using the MEL provisions of FAR 91.213 would be less onerous, the opposite may be true for some operators. An MEL can take all the work out of researching several documents to reveal that an instrument or item of equipment is required or not. The MEL puts all that research into an all-inclusive package and, for all practical purposes, takes the decision-making out of the hands of the mechanic or pilot. For a fleet operator, an MEL provides a uniform means of addressing any and all actions regarding inoperative equipment or instruments. Follow the instructions for the pilot or mechanic on a particular item, record the action and you are good to go.

So how do I get an MEL? Reviewing AC 91-67 and FAR 91.213 will head you in the right direction, although you may have to read and reread these several times. Determining that there is or isn’t an existing master minimum equipment list (MMEL) for your specific aircraft is a good starting point for your research. If there is already an aircraft make and model-specific MMEL, then it can be used to create an MEL for your aircraft that you will tailor to the needs of your specific operation.

You will need to generate a letter of request addressed to your area flight standards district office (FSDO) to start the MEL approval process for your aircraft or fleet. The FSDO will contact you to arrange for a meeting to discuss operations using the MEL and if the FAA official determines that you are aware of the requirements and responsibilities, you may be issued a letter of authorization. Thereafter, the applicant will submit a complete copy of the operations and maintenance procedures that they have prepared using various data such as maintenance manuals, operators’ manuals, airworthiness directives, supplemental type certificate instructions, etc. This can be a drawn-out process for the owner/operator in creating the MEL and time-consuming for the FAA official who’s doing the review.

When all this is completed, the FSDO may approve a MEL in a format for aircraft operations according to FAR 91 or 135. For aircraft operated under Part 91, the complete MEL approval documentation consists of the MMEL, the MEL for the specific aircraft, the preamble, a procedures document and the letter of authorization from the FSDO. This MEL “package” and letter of authorization for a specific make, model and serial number (or fleet) constitute an STC.

The STC and paperwork can not be sold or transferred, and if and when the aircraft is sold, the MEL and letter should be returned to the FSDO office that issued them. Should the aircraft or fleet principal of operations be moved to a different location, the FSDO office where the original MEL and letter of authorization was issued should be notified. You’ll also want to notify the FSDO for the new area of operation.

That’s the regulatory view from 30,000 feet. Now that you know about how to go about considering the aircraft’s airworthiness with inoperative equipment, it’s time to consider whether you should fly it.

Practical Applications

Operation with inoperative instruments and equipment should be given some serious thought. While a proposed operation may be legal, it may not be smart or safe for certain situations. This is where the pilot or mechanic must make the determination that not only is no hazard to the aircraft with an instrument deactivated or removed, the expected conditions of the planned flight must be considered.

A good example is a horizon gyro that is not working properly. Certainly, for VFR conditions this instrument is not required by the FARs. However, if your planned flight is at night over Lake Michigan with haze and low light conditions, it’s certainly not the smartest thing you could do. An inoperative landing light at night—presuming a not-for-hire operation—is another example. Sure, it’s legal, but is it smart?

Another example arises during your preflight inspection when you discover a VHF communication antenna has been damaged and is broken at the base. You won’t need the radio on your proposed flight. Since some force was required to break the antenna, it would be a good idea to have a mechanic determine that the aircraft was not damaged. Another determination is whether the antenna must be removed prior to flight or if the airplane can be flown as-is. Regardless, a placard indicating that the communication radio associated with the antenna placarded as being inop would be necessary. If the antenna was removed, the maintenance records, equipment list, and weight and balance records would need to be updated.

Putting It All Together

Operating an aircraft with inoperative instruments or equipment is as safe as the operator makes it. One takeaway from all this is that a quick decision in the affirmative that a flight with an inoperative item is safe really can’t be made without going through all the hoops—not only referring to the regulations or the MEL, but also considering the weather conditions that your intended flight may encounter.

Another takeaway is that this research doesn’t have to be postponed until something breaks. Using your airplane’s documentation and the relevant FARs, you can put together an expanded flowchart similar to the one on the opposite page to speed you through the decision-making process. It would be your own little MEL, tailor-made and ready to consult during your preflight.

Resources

Determining the airworthiness of an aircraft with inoperative or missing equipment can be a paperwork nightmare. If in doubt, don’t fly it. But if you want verification, are looking for a loophole or just want to educate yourself on what is and isn’t required to be working, these resources may be helpful.

Type Certificate Data Sheet

These are available free for the download from the FAA’s web site at tinyurl.com/avsaf-tcds and will detail the standard and optional equipment that must be installed per the type certificate. Information in the TCDS may have been superceded by AD or STC.

POH/AFM

The aircraft’s pilot’s operating handbook/airplane flight manual also will contain a list of required and optional equipment, as well as the limitations under which it must be operated, including placards, which must be present and legible.

STC Documentation

If the aircraft has been modified by a supplemental type certificate, the STC may include equipment requirements. If so, the relevant portions likely are included in the POH/AFM as an appendix of sorts. The documentation itself may be a no-go item if it’s not present. This is especially true for complex avionics.

Airworthiness Directives

An AD may have been issued against the aircraft requiring certain equipment or limitations. An example includes certain Beech Bonanzas and Debonairs, which must have a yellow range on each fuel gauge denoting the last few gallons. If that range is not present on the fuel gauge, the airplane likely isn’t compliant.

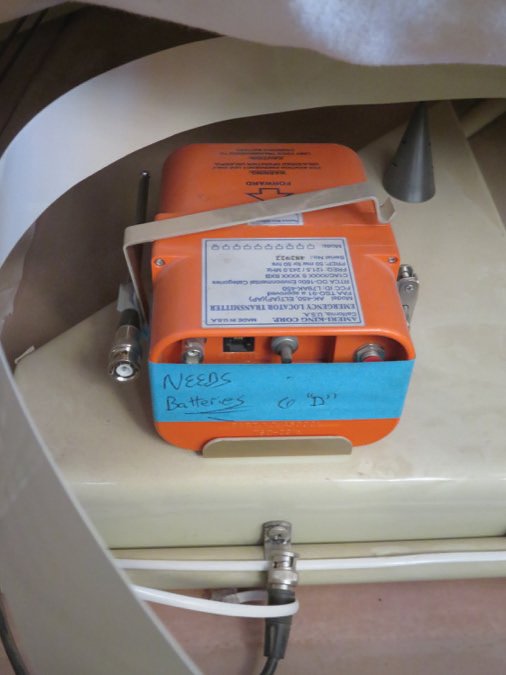

What About The ELT?

Modern emergency locator transmitters (ELTs) aren’t as problematic as they were when first mandated in the 1970s. Back then, a rush to prevent a rash of crashes in which it was difficult or impossible to find the wreckage resulted in a technology that wasn’t fully baked. Since then, the ELT has more or less been perfected and usually is required aboard the aircraft we fly.

There are exceptions, however, and an inoperative or missing ELT may not ground you. The FAA’s FAR 91.207 has the details, and you don’t need a functioning ELT if:

-The aircraft is engaged in training conducted entirely within a 50-nm radius of the base airport.

-The aircraft is used for cropdusting.

-The aircraft is not equipped to carry more than one person.

– When the ELT was temporarily removed less than 90 days earlier for inspection, repair, modification or replacement, and the removal is logged and placarded.

Mike Berry is a 17,000-hour airline transport pilot, is type rated in the B727 and B757, and holds an A&P ticket with inspection authorization.