The military operations area, or MOA, is the Rodney Dangerfield of special use airspace (SUA): It doesnt get any respect. Part of the reason few pilots pay much attention to whether a MOA is hot or not is VFR operations are allowed-at our own risk-in an active MOA. This is much different from a MOAs more-serious brethren, the restricted or prohibited areas, or even the temporary flight restriction. That doesnt mean punching through an active MOA is a good idea. In late March, two civilian pilots found out the hard way that what goes on in a MOA probably should stay there. Online sister publication

288

story like a wet blanket-including a podcast with one of the civilian pilots and another with an F-16 driver-and the story generated a lot of comments from rank and file pilots. Many of those comments evidence some misunderstandings of MOAs and SUA: What kind of operations is the military engaged in, anyway? Are civilian aircraft endangering themselves or military pilots by entering? Under what rules, if any, is the military operating when in a MOA? As often is the case in an online discussion, these and other questions got thrown about with no clear answers. But were here to help make sense of it all.

What The Heck Happened?

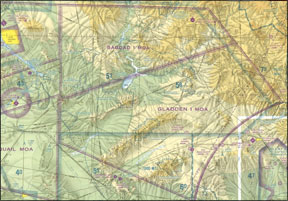

March 21, 2008, 16,500 feet over Arizona, in the Gladden 1 MOA. A Pilatus PC-12, flown solo by its owner, is VFR en route from Scottsdale, Ariz. (SDL) to Corona, Calif (AJO). A direct routing from SDL to AJO starts with a 275-degree heading; the two airports are 284.4 nm apart. Around 10:00 am Pacific daylight time, the PC-12s traffic collision alert system, TCAS, signals a collision threat a few thousand feet above and a few miles ahead of the big single, and closing.

The PC-12 pilot banked left and nosed down into a descending turn. The TCAS showed the threat, now 1000 feet above and closing, turned with him; then it showed above or below the PC-12. After banking right, climbing and re-establishing straight and level flight, the PC-12 pilot was astonished-putting it politely-to find an F-16 off his left wing, only “20 or so” feet away. According to the PC-12 pilot, the F-16 stayed in close formation for “15 or 20 seconds,” then slowly pulled ahead of the Pilatus before pitching up and disappearing, leaving the big single rocking in its wake.

288

The PC-12 pilot got on the horn to a bewildered ATC. A few moments later, a Beech Premier I bizjet, also on the frequency, also VFR in the Gladden 1 MOA and also at 16,500 feet, reported a similar encounter, right down to the TCAS alerts and an F-16 flying up close and personal.

Ultimately, both the PC-12 and Premier pilots made it out of Gladden 1 with their airframes intact, if not their shorts…but not before exchanging contact information on the frequency. As soon as he could, the PC-12 pilot filed a near-miss report with the FAA. That report is complete and has been forwarded to Luke AFB, the F-16s base. Its unclear at this writing if the Premier crew also filed an NMAC report.

We emailed the Pilatus pilot to follow up on various questions and details arising from this event, in addition to seeking contact information on the Premier. At our deadline, he had not responded.

HE SAID, SHE SAID

On the morning of March 21, the Gladden 1 MOA was “hot;” its normal times of operation are from 0600 to 1900 local. The MOAs altitudes vary from 5000 to 7000 feet agl-whichever is higher-to 17,999 feet, or the base of Class A airspace. Air traffic control assigned airspace, or ATCAA, overlies the MOA, allowing military operations to continue to FL510.

Of course, MOAs are a type of special use airspace in which the military conducts training or testing maneuvers. They exist to ensure separation between those supposedly “nonhazardous” military operations and IFR flights, plus alert VFR operators on where, at what altitudes and when such training or testing activities are conducted.

According to Maj. Miki Gilloon, chief public affairs officer at nearby Luke AFB, there were four F-16s in the Gladden 1 MOA that morning, conducting “a typical two v. two tactical intercept training mission.” Maj. Gilloon told us after the two civilian

288

aircraft were noticed, an F-16 pilot “attempted to identify the aircraft traversing through the airspace in order to contact the civilian pilot and educate him about the risks of transiting an active MOA.” Further, according to Maj. Gilloon, no F-16 got closer than 600 feet to either the Pilatus or the Premier as verified by radar and HUD tapes.

Maj. Gilloon characterized the F-16s intercept as “a properly executed standard maneuver” similar to establishing visual contact with a flight leader or a refueling tanker.Meanwhile, the other three F-16s were in “administrative holding patterns.” The F-16 conducting the intercepts was the training missions lead.

Maj. Gilloon confirmed an internal safety investigation surrounding the episode is still being conducted at Luke as this issue of

Aviation Safety was being finalized. She added, “Thus far we determined the F-16 pilot did not violate any existing military practices or procedures for operation of a military aircraft in the MOA.”We also contacted the FAA regional public affairs office responsible for Gladden 1. That office confirmed an investigation of the near-miss complaint filed by the Pilatus pilot was completed and its results were forwarded to Luke AFB. The FAA has no jurisdiction over military operations, however, and cannot control what happens next. Maj. Gilloon confirmed the Air Force received the FAAs report “and is using the information provided as part of our ongoing investigation.”

Whos right?

There are almost as many opinions on this episode as there are N-numbers. Some say the Pilatus/Premier drivers got what they bargained for. Others say the F-16

288

pilot was irresponsible. A few decided they will never again venture into a hot MOA. Whos right? Whos wrong?

Everybody. The TCAS-equipped Pilatus and Premier apparently responded to warnings as they should have. And until the FARs are changed, its perfectly legal for the Pilatus/Premier to have been where they were. However, along with using the option of transiting a hot MOA, one must accept the ensuing increased risk. Whether all pilots know and understand the risk includes being “played with” by an F-16 is open to debate. Wed argue they dont.

In fact, we specifically asked the FAA whether it has any guidance for civilian operators of TCAS-equipped aircraft regarding operations within active MOAs. In response, we were simply referred to that portion of the AIM which states: “Pilots operating under VFR should exercise extreme caution while flying within a MOA when military activity is being conducted.”

While only two people really know how close the F-16 got to the Pilatus, the F-16s actions raise a question: Does the military have

carte blanche to get in close formation with us in an active MOA? Pretty much, yes.Whether the F-16 acted appropriately is arguable. Wed suggest the kind of aggressive maneuvering reportedly engaged in by the F-16 isnt necessary to accomplish the stated objective: identifying the “intruding” aircraft. Wed also suggest the F-16 did more harm than good by countering the Pilatus avoidance maneuver.

So far, however, the USAF is unapologetic, explaining the F-16 followed procedure. Maj. Gilloon again: “Our pilot did

not employ combat tactics against the civilian aircraft. This was a controlled maneuver to ensure that neither aircraft was placed in any danger.”Conclusions

Its clear to us the Pilatus/Premier legally transited a hot MOA under VFR and were targeted for interception by the F-16 pilot. Its equally clear the lone F-16 went out of its way to conduct the intercept, countering the TCAS-related evasive maneuvers in which the Pilatus engaged.

Despite the USAFs contrary statements, we feel the F-16s reported actions were irresponsible and created unnecessary increased risk for the two civilian aircraft. The F-16 pilot had no way to know what was going on aboard the “targeted” aircraft or how it would react.

A high-performance military aircraft performing what can only be considered counters to avoidance maneuvers and then flying formation with a civilian aircraft, regardless of where, when or the perceived justification, isnt appropriate. Demonstrating the ability to perform such an intercept on a Pilatus PC-12 attempting straight and level flight at 16,500 feet doesnt impress us. We question the F-16s need to perform the kind of maneuvers the PC-12 pilot reported.

All of that said, its equally clear VFR operators in a hot MOA must accept an increased risk level. That risk includes fighter aircraft “operating at supersonic airspeeds and rapidly changing altitudes,” according to Maj. Gilloon.

Lets all be careful out there.