There is a fundamental reason we perform preflight run-ups and engine checks before takeoff: It is a whole lot better to find problems at 1G, 0 feet agl and 0 knots airspeed than it is while airborne. Making sure a powerplant will work as we intend before taking off is just good airmanship. A good run-up doesn’t mean everything is perfect, however, and we train for airborne engine problems, including full use of its controls and instruments.

Sometimes, though, the problems we’re looking for don’t reveal themselves when it is convenient for us, and we have to diagnose engine issues in the air. Urgently. And fly the airplane at the same time. It is not a comfortable experience. I was recently reminded of this while flying with a fellow pilot, whom I’ll call Roger, who simply needed some instrument dual in his Cessna 182.

“DID YOU FEEL THAT TOO?”

After a very clean and thorough run-up—Roger consistently impresses me with the best checklist discipline of any pilot I know—we took off to intercept the nearby VOR to do a few holds and then head outbound to log the requisite simulated instrument time. As we climbed, I briefly took control of the plane so my fellow pilot could don his hood. We both felt a momentary engine hesitation somewhere along the way, so brief it was barely noticeable. Maybe Roger bumped something while reaching for the ungainly plastic view-limiting hood.

Looking a bit like a dog returning from the veterinarian, Roger took back the controls, and we completed the climb to 7000 feet msl with the engine sounding smooth. We did a few turns in the hold and proceeded outbound. Then things got interesting.

On reducing power and configuring for cruise, the engine started missing…a lot. We weren’t in actual clouds, but they were nearby and relative humidity was high. It was a cold winter day, and the previous day’s weather had been quite rainy and snowy. From inside his dog-collar-hood-of-shame, Roger shared a story from a few years earlier of a pilot in a rental 182 who did a precautionary landing due to carb ice. Cessna 182s of the vintage of Roger’s plane are notorious for forming carb ice, so we both agreed it was a reasonable suspect. He applied carb heat and, sure enough, as the carb-temperature gauge’s needle climbed from the yellow zone into the green, the engine smoothed out. We congratulated ourselves we had the problem licked.

ARE YOU SERIOUSLY DECLARING AN EMERGENCY FOR A FOULED PLUG?

When you aren’t 100-percent confident the engine will continue running, doesn’t it seem reasonable to just be the center of attention for a little bit? I learned this lesson in my Cub. I had just departed the airport, and was a few miles out, when the engine starting running very rough and losing power.

D. Miller/Creative Commons

I tried carb heat, but was losing altitude. I called the tower, told them I had a rough engine, couldn’t hold altitude and would be returning to land in the opposite direction on the runway I just departed. That meant landing with a tailwind, which was the least of my problems because for a mile or so, I wasn’t sure I would make it back.

Despite my Cub’s power loss and inability to hold altitude, once I had the field made, I asked for a clearance. But I didn’t declare an emergency. That turned out to be one of the stupider decisions I have ever made, because when I looked at the other end of the runway, I saw a jet ready to take off.

If the tower had cleared me to enter downwind to let the jet depart, I would have had to accept a plowed field rather than a runway. Fortunately, telling the tower I had a rough engine and needed to land opposite direction clued them in. However, after that experience, I won’t ever hesitate declaring an emergency again.

At a non-towered airport or en route, it may not matter if you declare an emergency over the radio—if no one hears you or can do anything about it, does it matter? There’s nothing in the FARs saying you have to declare an emergency to have one, just that you can deviate from them enough to resolve the emergency.

DIAGNOSIS

After a few minutes with carb heat in, we decided we could resume our trip to the next VOR. Upon taking the carb heat out, however, the engine started coughing again, even worse than before. For a moment, it made no sense. If it was carb ice, the dose of carb heat should have done the trick.

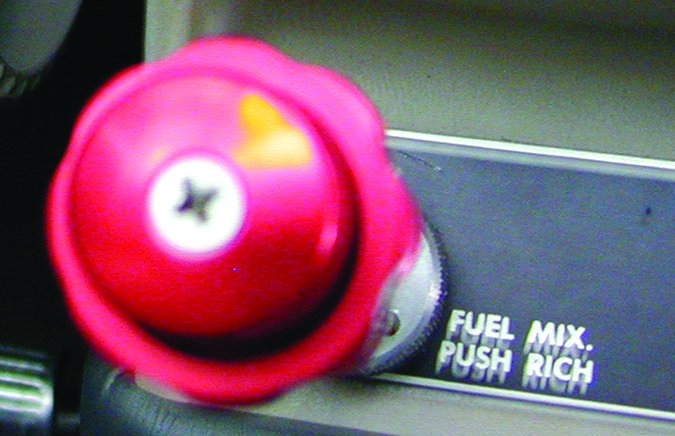

We discussed it briefly and decided perhaps we now had a fouled plug that was worsened by running over-rich with carb heat. So we adjusted the mixture settings. Repeatedly. But no red-knob position seemed to resolve the issue. Every time we returned to cruise settings, the engine was rough.

Finally, we did a magneto check. This is one of those tests where having an engine monitor is well worth the relatively small investment. On one magneto, the engine smoothed a bit. On the other, it got much rougher and the EGT on cylinder 3 dropped precipitously. Our final diagnosis: We had a spark plug issue on cylinder 3, likely a fouled plug. But a reasonable diagnosis that fit all the facts we had was only part of the challenge. We still needed an action plan.

DECISION TIME

As I write this now, in the comfort of my office chair, our diagnosis was pretty solid. Despite the data and positive diagnosis, confident is not the word I would use to describe the way I felt at the time. Even though we had excellent data telling us the number three cylinder had a bad spark plug, the one powered by a certain magneto, a rough engine while in flight is not something promoting confidence. Instead it provides a great deal of concern and skepticism. I also know that whenever you choose to ignore something unusual, whether it is in flight or on the ground, it starts a chain of events leading to an unforeseeable conclusion. I could imagine the opening statement of an NTSB report, “After experiencing a rough engine and determining it was a fouled spark plug, the pilots continued….” The best way to break the accident chain is stop any escalation of events.

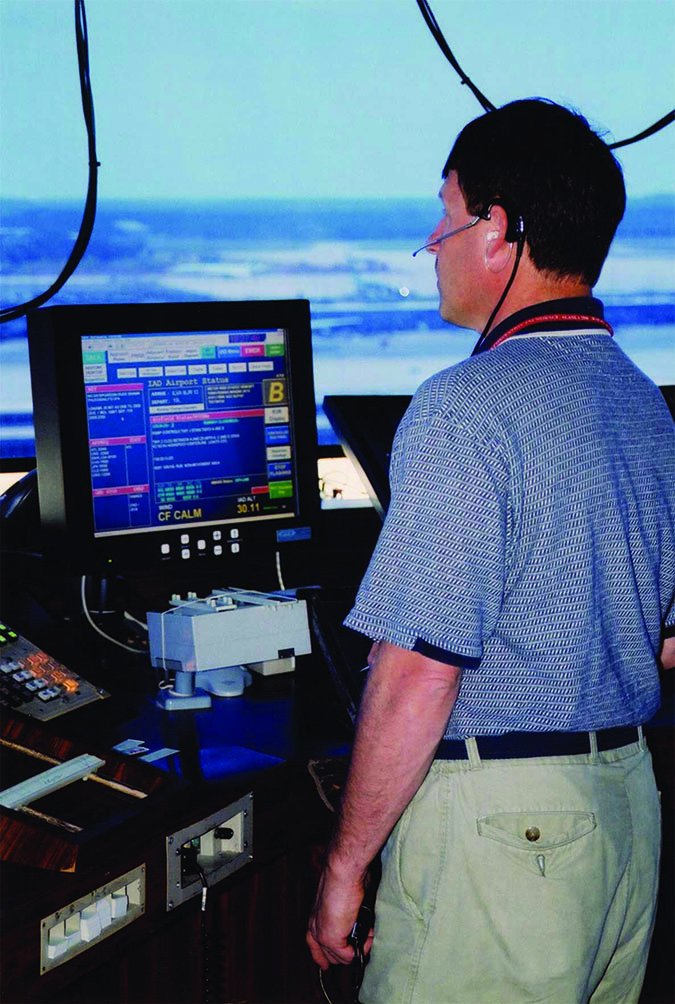

We both agreed it was time to return to the airport. The engine wasn’t so rough it was losing power, but it was sufficiently rough we did not feel warm and fuzzy. We called the tower to let them know we would be returning to the airport with a rough engine. And, more importantly, we declared an emergency.

Technically, when coming into an airport, you follow normal procedures and get to pattern altitude to ensure smooth flow of traffic. But by declaring an emergency, we gave ourselves clearance to land as well as permission to stay as high as we wanted throughout the approach. As we did our 180 back to the airport, there was no rush to descend. We had no need to get to pattern altitude until we were 100 percent confident we were in gliding distance of the runway.

PLANNING FOR NO POWER

With the runway in gliding distance, all that was left was pulling power to descent. The engine was sufficiently rough that I questioned whether it would continue running at all after a power reduction. With no choice, and a great deal of trepidation, we started down…and everything went like clockwork. We landed a little longer than usual due to the higher starting point for our descent and naturally, the engine ran smoothly, as though any problems were all in our head.

It was amusing to have a fire truck escort us all the way to the hangar, but that’s usually what happens when you declare an emergency at a towered airport. All in all, it was a smart move. You are always better safe than dead, and the fire crews can use the practice to get the cobwebs off their fire-retardant suits.

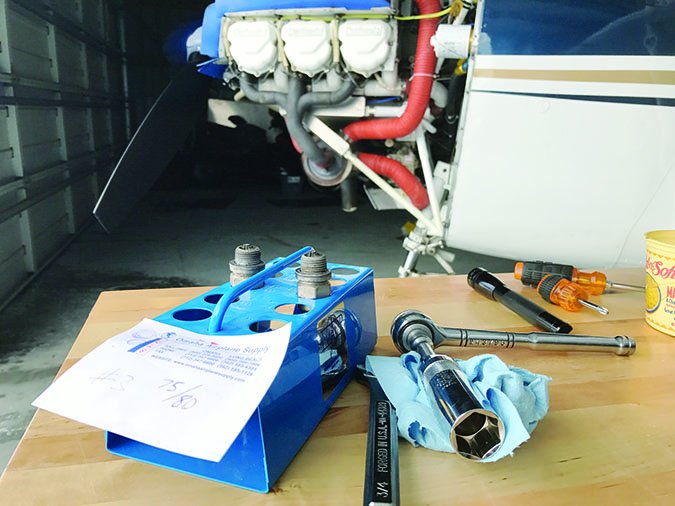

In the end, our diagnosis was correct. The plugs needed to be changed. Roger and I agreed that while fouled plugs are a very minor thing, they can sure grab your attention in flight. Moreover, they provided us with some great experience on how to handle a real emergency. A rough-running cylinder 3 could just have easily been on the verge of eating or flinging a valve.

It was instructive to have experienced the event together and then afterward have the opportunity to reexamine it from a distance. When the engine was misbehaving, we tried to make it run smoothly. When it didn’t cooperate, and even got worse, we returned to the airport with an emergency declared in case the engine quit. Taking the most conservative approach to completing our flight was the right choice.

PREVENTING LEAD FOULING

Avoiding prolonged low-power operation is key to avoiding lead fouling. The two coolest places inside the cylinder are the point of the spark ignition and the exhaust valve outlets, which creates the optimal conditions for vaporized lead oxides to condense as a liquid and cool to a solid. These conditions tend to occur at startup, descent and taxi after landing.

After startup, operate your engine at 1000-1200 rpm for the initial warmup period and not at idle speeds. The higher pressure helps rings seal, which reduces corrosive combustion byproducts going past the rings and into the oil. This reduces both corrosion problems and the amount of lead being pumped into the oil. At idle rpm, lead deposits are more likely to form because of the low combustion temperatures. This is where aggressive leaning on the ground can help. At taxi power settings, lean the mixture as much as you want—you won’t hurt the engine.

Rotate low spark plugs to top position, and remove, inspect and clean spark plugs that might be suspect. Lower plugs in an engine run dirtier than the top plugs. If the engine is running massive-electrode spark plugs like the one pictured at right, changing to (admittedly more-expensive) fine-wire plugs may help cure lead-fouling problems.

Smooth application of power during takeoff reduces chances of lead fouling, which tends to make itself known at high power settings.

Engines that have been involved with long, low-power descents, or have taxied for some distance, may have low cylinder temperatures that lead to lead fouling.

Engine manufacturers often have specific recommendations, but it is a good practice after landing, and once the temperatures are stable, to briefly increase engine speeds to 1800-2000 rpm for a count of 10-20. This should be enough temperature rise to burn off lead deposits. Then reduce power to 1000-1200 rpm once again before shutdown using mixture control.

“BURNING OFF” A FOULED PLUG

A lot of people these days are surprised to learn aviation gasoline contains lead. The current fuel, 100LL (or low-lead), in fact contains much less lead than the aviation gasoline it replaced, 100/130 octane (green gas). But engines designed for 80 octane fuel (red), which is no longer available in the U.S., and operated on 100LL (blue), can experience lead-fouled spark plugs. The Continental O-470 variant in Roger’s Skylane is one of those engines. So was the O-200 in the Cessna 150 I trained in

Primary students flying trainers back then were told to put the mixture control into the full-rich position and leave it there until shutting down, at least until they began to fly cross-countries. So lead-fouling was an occasional issue.

I don’t remember the first time an instructor taught me to “burn off” a fouled spark plug. But we likely had a slightly rough magneto during the run-up. With feet firmly on the brakes, the instructor boosted the engine’s rpm up to 2000, and slowly leaned the mixture. At the point the engine began to stumble, he stopped leaning and let it run like this for maybe 15 seconds. By then, it had smoothed out. Then he reduced rpm back to the checklist’s 1700 and repeated the mag check. Everything was good to go.

Leaning the mixture to near peak EGT at a high rpm—but not a high enough power setting to risk damage—increased both exhaust gas and cylinder head temperatures enough to melt the accumulated lead from the spark plug(s). If you’re running a relatively low-compression engine and occasionally have a less-than-perfect mag check, it might be due to lead fouling, and burning off the lead by increasing the cylinder’s temperature can help. — J.B.

Mike Hart is an Idaho-based flight instructor and proud owner of a 1946 Piper J-3 Cub and a Cessna 180. He also is the Idaho liaison to the Recreational Aviation Foundation.