After living on the U.S. East Coast, I have now lived in and enjoyed the Pacific Northwest for 14 years. Along the way, I’ve learned to respect the limitations of flying single-engine piston airplanes for business and personal travel. It’s much different than on the East Coast, with its own set of hazards and associated risks from weather, terrain, airspace and isolated geography.

The Pacific Northwest, for the purposes of this article, includes the states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and parts of Montana and Wyoming. That’s a huge hunk of territory and comprises more than 250,000 square miles for Washington, Oregon and Idaho alone. The region includes two major mountain ranges—the Cascades and the Northern Rockies—and many smaller ones, as well as several major river basins. There are major cities in the region, such as Seattle, Portland and Boise, but also thousands of square miles of largely empty land and wilderness.

The Mission

Your specific mission will dictate how you operate in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) and how you will identify, assess and mitigate risks. Both local and cross-country flights come with their own sets of hazards and risks. If you are using your airplane for business or personal transportation, you will find that schedule flexibility is one of your best risk mitigation tools.

Local flights in the Puget Sound area are both visually rewarding and somewhat easier to manage with respect to risk, since you are essentially operating from near-sea-level airports. If your mission involves traveling within the region but beyond Puget Sound, the nature of your planning and risk management will change.

You’re likely to be affected by multiple changes in weather, terrain and airspace, and face some complex risk analysis. The aircraft you operate will greatly determine the level of all-weather, go-anytime utility you can achieve. A pressurized, ice-protected turboprop gives you many more options than would a non-ice-protected, non-turbocharged piston single. It’s likely your mission can be accomplished with the piston single, just perhaps not on the schedule you want.

When your mission is to depart the region, then most roads lead east or south. Sometimes, you will need to follow a complex route to avoid hazards, greatly adding to total trip distance and time. The ability to change your schedule, even at the last minute, is your biggest mitigation tool. The sidebar on the opposite page explores this in greater detail, including alternatives if icing or other weather conditions make going due east problematic. The sidebar on page 6, meanwhile, highlights the issues with following one of the popular VFR routes, the Columbia River Gorge.

Weather

The are two major weather generators in the PNW, the Pacific Ocean and terrain, specifically the two major mountain ranges and especially the Cascades. These influences will often generate risks that affect small aircraft operation all year long.

To oversimplify, the PNW’s weather is largely governed by what happens in the Gulf of Alaska. In the summer months, there’s often a high-pressure area sitting out there that brings fabulous weather to the Northwest, including weeks on end of clear skies. During the winter months, low-pressure systems bring low ceilings and drizzle, and occasional heavier precipitation. Convective activity is rare west of the Cascades, but not to the east. However, unlike the Midwest, convection doesn’t often occur as a line of thunderstorms but generally as individual cells.

The main risks from weather hazards in the Northwest is icing, and it can be a year-round hazard for piston-engine non-ice protected aircraft. The main issue when operating IFR in the region is that the minimum en route altitudes (MEAs) usually are above 10,000 feet, which often means a constant threat of airframe icing. It can be especially aggravated by upslope conditions on the western side of the Cascades, which can produce especially heavy icing conditions.

Terrain

The PNW’s terrain generates several hazards for general aviation operations. The high MEAs required to operate over the mountain ranges can prevent a challenge to low-performance aircraft, even without the icing. Another hazard involves operations at high-altitude airports. ThePNW has quite a few airports above 6000 feet, especially in Idaho, western Montana and Wyoming. In the summer, this can produce density altitudes approaching 10,000 feet. Non-turbocharged aircraft will be faced with lengthy takeoff distances and anemic climb rates. This can also affect operation during IMC conditions, since many of these airports have IFR departure procedures with minimum climb gradients.

Another hazard is the isolated, heavily forested terrain. All the PNW states have large, sparsely populated wilderness areas and airports are few and far apart. In some cases, they’re very limited. Aviation Safety contributor Mike Hart gets paid to fly in the PNW’s backcountry, and his writing often explores backcountry airstrip operations in great detail.

Mitigating these terrain hazards may require you to deviate from straight-line routes in favor of operating through valleys or away from poor or wilderness terrain. Departing the Seattle area under IFR, there is one airway that crosses the Cascades at an MEA of 8400 feet. Alternatively, you can fly further south and fly through the Columbia River Gorge at an MEA of “only” 7000.

Departures from high-altitude airports should take place early in the morning, when temperatures are lower. You should also consider carrying survival gear and make sure your ELT is operational.

Airspace

Unlike some areas in the U.S., the PNW has very little congested airspace. Seattle is the only Class B, but it can present transit problems since it’s wedged between the Cascades and the coastal Olympic range. There is Class C airspace at several other locations.

A bigger issue may be military special use airspace, especially military operations areas (MOAs). The MOAs are ubiquitous in the western U.S., although the PNW seems to have fewer of them than other areas, such as the Midwest and the South.

Mitigating airspace and airport hazards is best accomplished through meticulous pre-flight planning. Most of these hazards don’t represent go/no-go decisions but rather demand careful analysis of Notams and aircraft performance. The Mooney 201 is generally not considered a bush plane, but I safely operated my previous 201 out of several isolated unpaved runways in Montana. I advise getting training before attempting to fly to any of these locations.

Pilot and Aircraft

The environment is certainly a huge area of potential risks when flying this area, and the pilot and aircraft risks can be an adjunct to the environmental hazards. Let’s examine the delta for these factors: the risks that are aggravated by PNW operations. Pilot risks can be analyzed in two separate buckets: qualification issues and aeromedical factors.

Qualification issues come into play when a pilot desires to operate from wilderness airstrips or those at high density altitudes. In some cases, such operations will call for skills that were never acquired or are rarely practiced. These risks must be mitigated by careful preflight planning and perhaps a course in mountain flying.

Any aeromedical issues may be magnified by the higher altitudes needed to operate safely in the region. You will find yourself flying at 10,000 feet and above on many operations, even flying VFR. When flying above 10,000 feet, you should use supplemental oxygen if you are not operating pressurized equipment. This would include carrying and using a pulse oximeter.

Aircraft risks in the PNW can be aggravated if you are operating non-turbocharged piston equipment. If your mission is transportation, you should choose an aircraft with good operating characteristics above 10,000, including the ability to climb there in a reasonable amount of time.

External Pressures

External pressures sometimes generate the most insidious risks for pilots, and this is especially true when operating in the PNW. Some conditions in the region, when combined with aircraft and sometimes pilot limitations, can simply mandate the cancellation of a trip due to unacceptable risk. In my own operations, I mitigate risk by planning way ahead on a proposed trip, so I can make other transportation arrangements or reschedule or cancel upcoming events.

My mitigation strategy is best illustrated by how I managed a recent six-week business trip with 18 stops covering the entire U.S. in my Mooney 201. The trip had four core stops with meetings or events that I really needed to get to. I added 14 more stops to visit current or potential clients. I have up-front understandings with these clients that my meeting date would be subject to change. Starting in early September, the departure weather was fine, so I began on schedule. The rest of the trip mostly stayed on schedule also, despite having to dodge two hurricanes in the Southeast—the opposite of the PNW in more ways than I can possibly describe. On the return legs, I spotted an incoming low-pressure area on the prog charts several days in advance. I canceled my last two stops, so I could return to home before the arrival of the low and its attendant icing conditions.

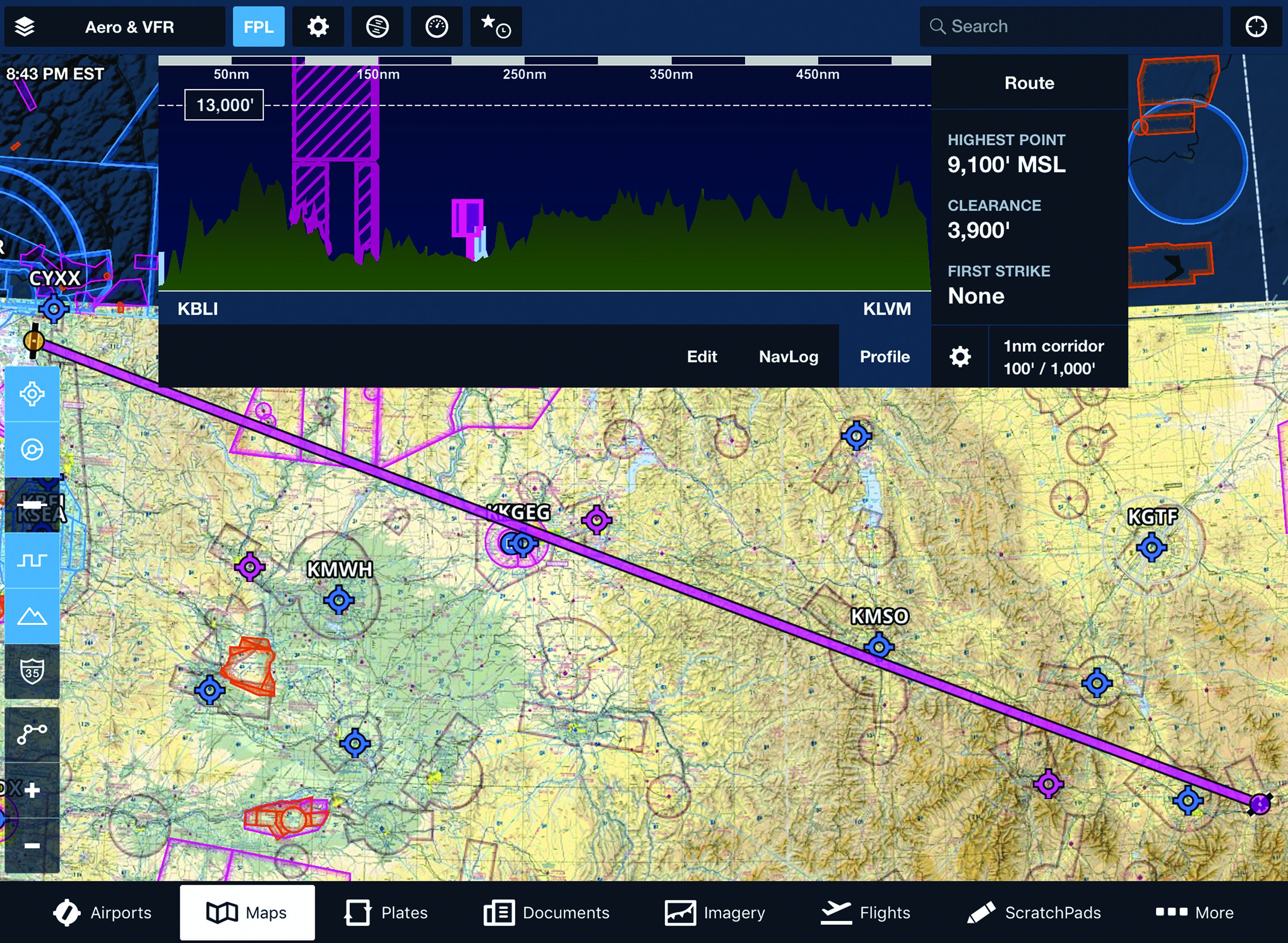

The screenshot above depicts a hypothetical flight from the west end of the Pacific Northwest to the east end. That would be from Bellingham, Washington (KBLI), to Livingston, Montana (KLVM). That’s a 527 nm flight I have made several times in my current aircraft, a Mooney 201, and the V35B Bonanza that preceded it. The terrain itself and the weather it generates creates hazards and risks that must be managed.

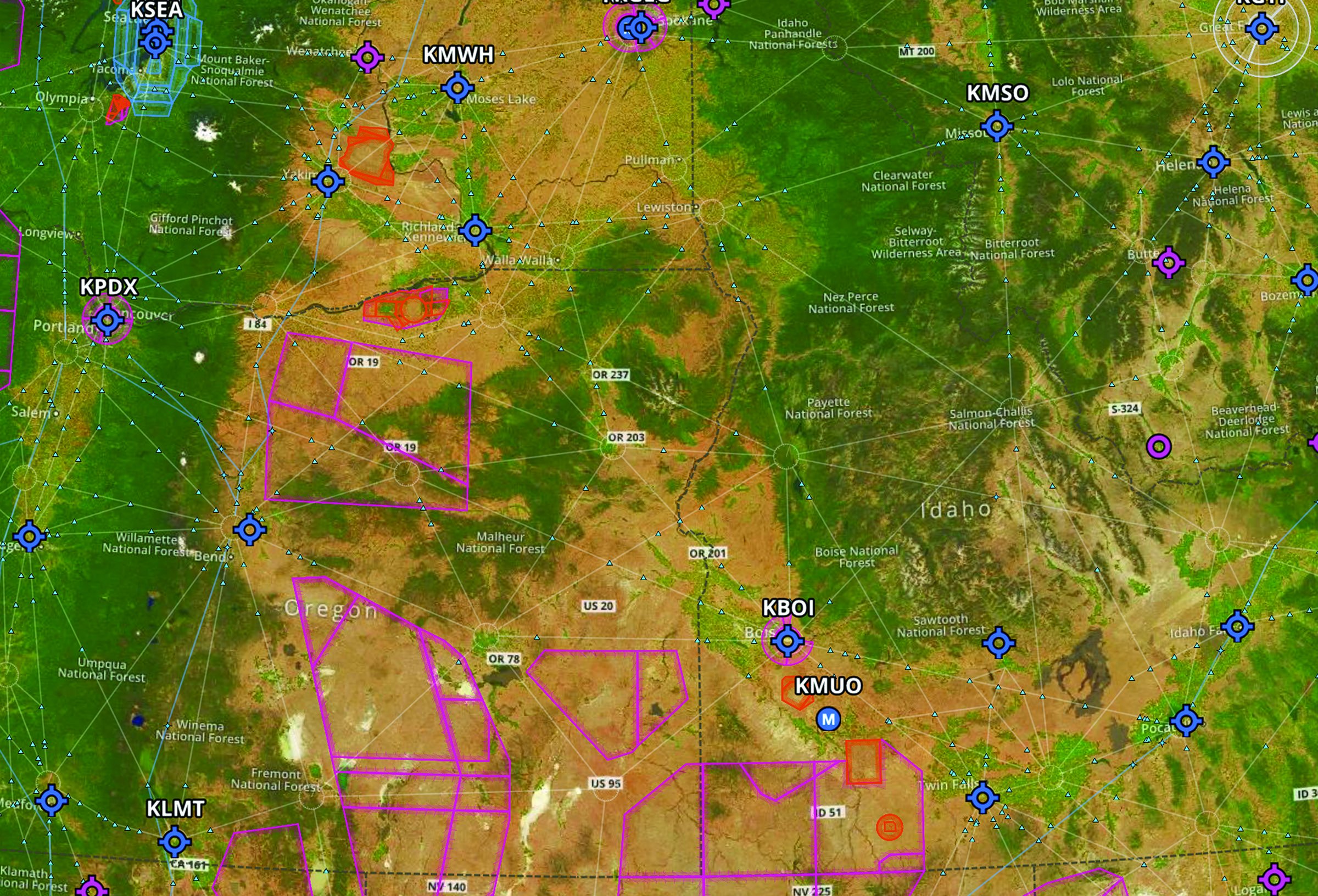

The screenshot below shows the Pacific Northwest terrain with Bellingham nestled in the upper left corner in the shadow of Seattle. Crossing the mountains to go east is fine when there’s no icing and you don’t mind going IFR. Otherwise, you’ll head south first, before going east, perhaps along the Columbia River Gorge, east of Portland (see the sidebar on the next page). If your destination is off to the southwest, there is an obstacle course of special use airspace over eastern Oregon and southern Idaho.

Single-Engine Profiles and Routes

My own rule of thumb for operating a non-icing-approved piston single in the Northwest is to conduct all flights, other than purely local flights, on an IFR flight plan or with VFR flight following from ATC. Rarely will I file a VFR flight plan, since ATC already knows where I am. I also try to use routes that keep me away from rough terrain, unless I can fly high enough to glide to airports or suitable landing areas.

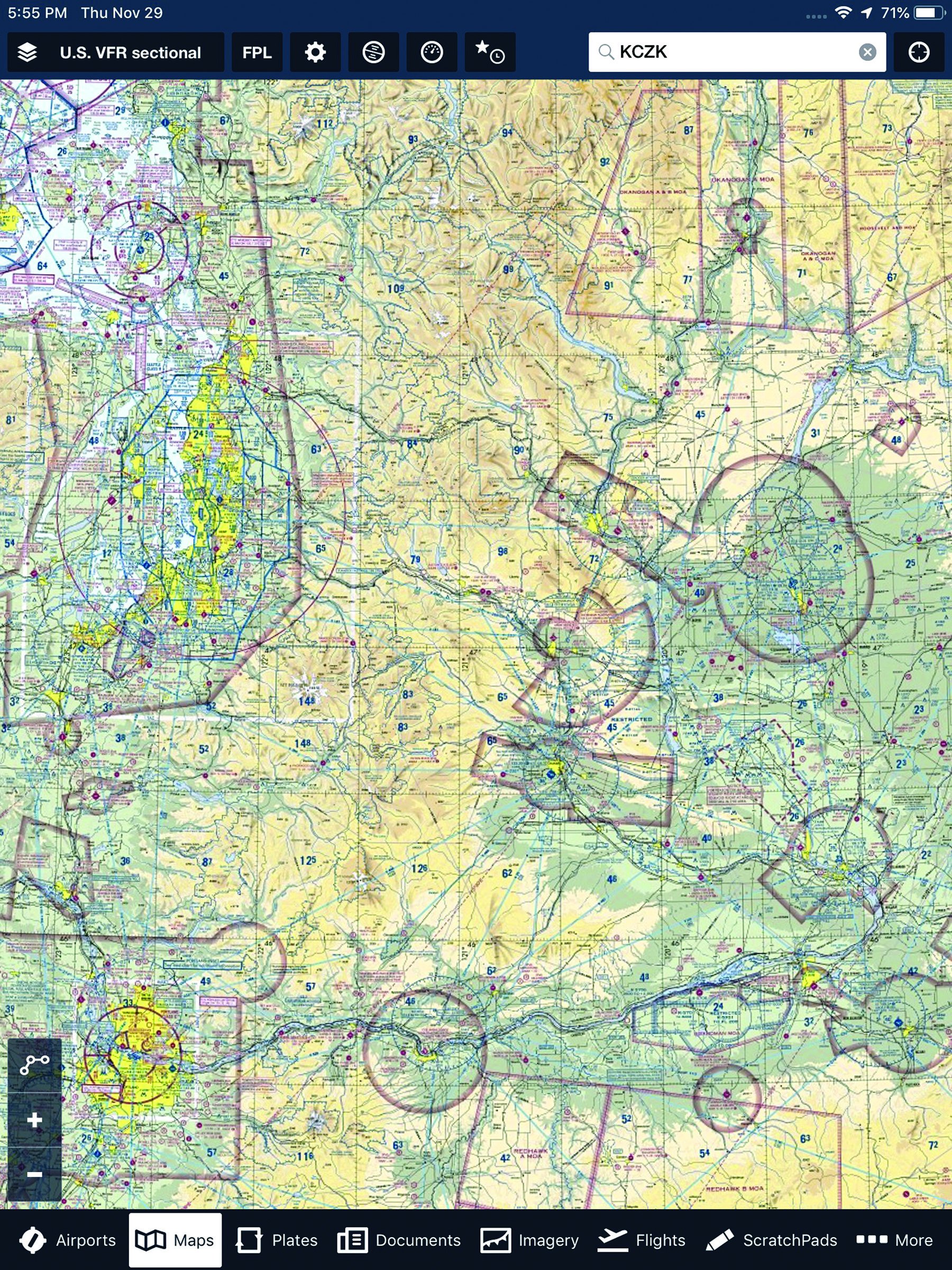

Sometimes, I will fly even further south before heading east. I can then cross the Cascades through the Columbia River Gorge IFR at 7000 feet and lower under VFR. “Shooting the gorge” has been a time-honored practice since Lewis and Clark. However, if you do it at low altitude under VFR, to stay under an overcast, examine the sectional chart excerpt at right. There is high terrain on each side of the river. In marginal conditions, you might want to reconsider. When the Cascades are totally obscured and icing begins at 6000 feet, it’s sometimes possible to head even further south to Northern California before heading east. This could be practical, if your destination is the Southwest or Texas. However, be advised that you will still have to cross the Siskiyou Mountains in Southern Oregon and Northern California, where the IFR MEA is 10,000 feet.

The Prog Is Your Friend

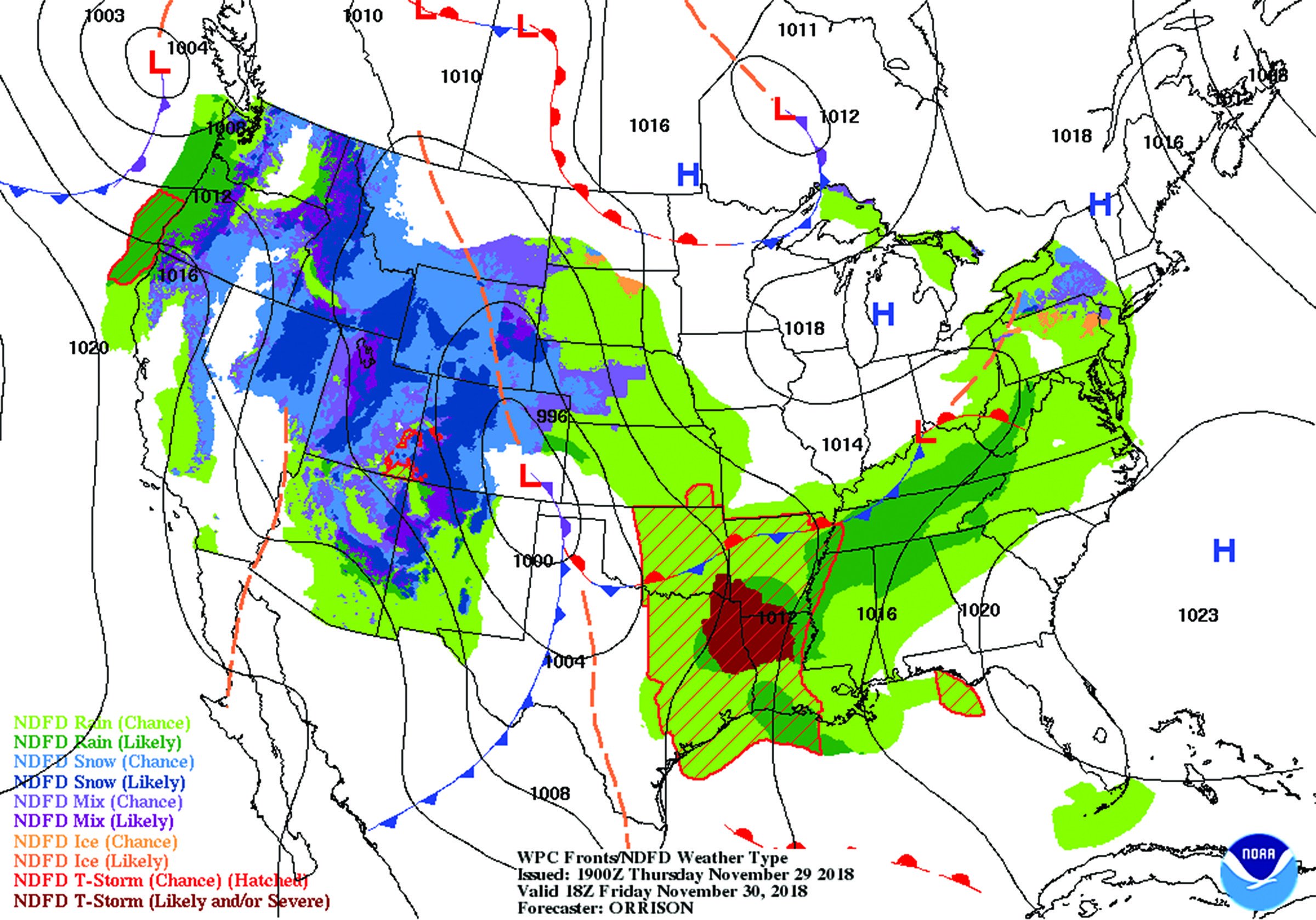

When trying to mitigate icing hazards and risks in a non-ice-protected piston single, your most effective mitigation is avoidance. In other words, you must take a different route, change altitudes, or accelerate or delay your departure. In my own case, I begin this analysis days before a planned flight as I watch prog charts. Here’s an example of one you probably want to work around when flying in and around the Pacific Northwest in a piston single with nothing but a warm pitot tube.

Implementing Mitigations

If you plan to fly the Northwest, but are not based here, do not be intimidated by the conditions I have described. Consider the following three main points:

• Always practice effective risk management and identify, assess and mitigate all risks to acceptable levels before departure and while in flight.

• Remember that schedule flexibility is your best mitigation tool. It’s okay to cancel or reschedule a flight.

• Consider taking some training before arriving. This could include a risk management course or a mountain flying course.

Those steps, at a minimum, will help you enjoy your flights and most likely enable meeting your mission requirements, whether they are for transportation or to just enjoy the region.

Robert Wright is a former FAA executive and president of Wright Aviation Solutions LLC. He is also a 9900-hour ATP with four jet type ratings, and holds a flight instructor Certificate. His opinions in this article do not necessarily represent those of clients or other organizations that he represents.