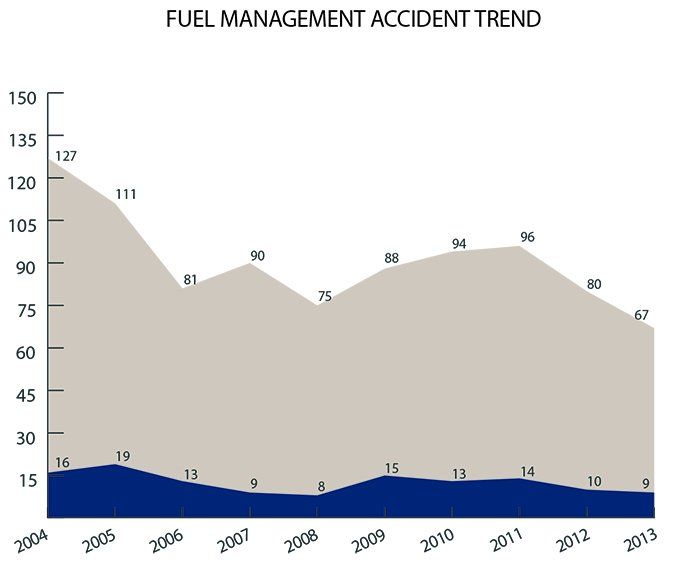

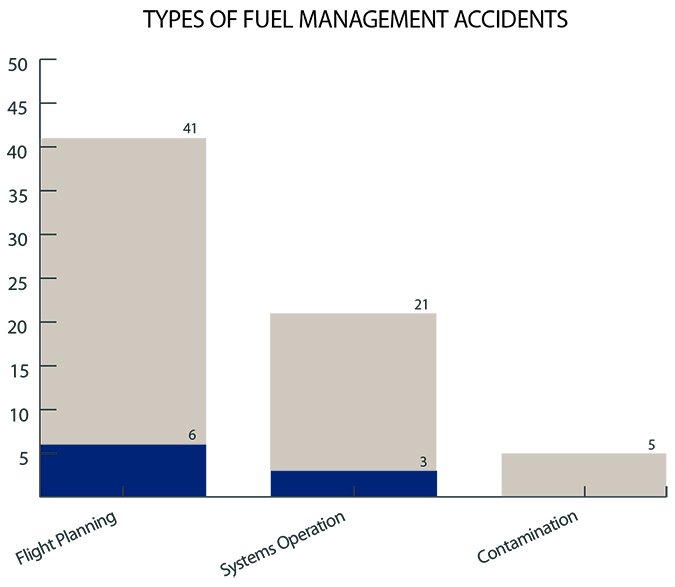

The good news about fuel-related accidents is they seem to be stable in occurrence year over year, and perhaps trending slightly downward. It’s a bit too soon to tell if a recent downturn is an aberration or the new normal, but we’ll know more in a couple of years. The bad news is they continue to be preventable. In fact, a thorough understanding of the fuel system for the aircraft you fly is critical to further minimizing these kinds of accidents. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the three basic categories of fuel-related accidents—planning, systems operation and contamination, according to the AOPA Air Safety Institute’s 25th Nall Report—seem to occur more frequently as aircraft system complexity increases.

According to the Nall Report, “Retractable-gear and multiengine models made up 45 percent of the airplanes involved in fuel-management accidents. This is more than one and a half times their proportion of non-commercial fixed-wing accidents overall, in which they accounted for less than 30 percent.” In other words, when an airplane is equipped with multiple fuel tanks, multiple engines, boost pumps, transfer pumps and switchable gauges, the opportunity for mistakes grows. Let’s see if we can simplify things.

How Fuel-System Accidents Happen

The best example of the kind of complexity I’m thinking about comes from flying an early Beechcraft Model 35 Bonanza on a short VFR night cross-country. I thought I was familiar with the Bo’s fuel system, but I was proven wrong. This particular aircraft was different—it had tip tanks and an additional, separate fuel selector valve. Unless modified, early Bonanzas reroute excess fuel that is not consumed by the engine to the left main tank, regardless of which tank is selected to feed the engine during operation.

While flying over mountainous terrain about 25 miles from my destination late one night, I noticed the fuel pressure needle bouncing off zero, followed quickly by the low fuel pressure light. I also noted the left tank’s fuel gauge showed it was full, so I switched tanks from right to left and expected to regain engine power momentarily. Out of the corner of my eye (long before Loran or GPS was available, with their “nearest” button) I saw a rotating beacon and turned toward an airport several miles away.

I set up for best glide, pulled the prop into low RPM, checked the fuel selector position and went for the checklist. Unfortunately, the flashlight in the seat back pocket didn’t operate and the lamp designed to illuminate the fuel selectors also was inoperative. As I neared the airport, I lined up on final, put the gear down and landed.

After moving the plane to the ramp and finding a working flashlight, I discovered the left main tank was indeed full, but the selector I was positioning from left to right was the selector for the empty tip tanks. Meanwhile, the main fuel selector was selected to right main tank, which was empty. I learned a lot of lessons that night, the most important of which is to know how the fuel system operates in the plane you fly. Modifications such as tip tanks require further knowledge to prevent what happened on this flight.

Fuel System Design

The fuel systems incorporated into all type-certificated aircraft are required by regulation to include items like fuel system drains, filters or screens, properly marked fuel valves with positive detents and a positive shut off. Additionally, the system must incorporate fully functional fuel vents and fuel caps designed to operate in all phases of flight without loss of fuel.

Fuel quantity gauges are required equipment for each fuel tank along with accurate indication when the tank is empty. Each fuel tank is required to be properly marked with the minimum fuel grade and quantity. Modified aircraft may have additional requirements with which you must comply, and airworthiness directives may impose additional limitations.

Regardless of all the safeguards built into an aircraft’s fuel system—and perhaps because of them—flight planning is still a necessary task even if you are just off for a $100 hamburger. How much fuel is required for your flight, what are the reserve fuel requirements, what weather should you expect along your route of flight and at your destination?

Are there any Notams issued for your intended flight, including anything on fuel availability at your lunch destination? Winter is here and conditions can change quickly. For example, an airport may report VFR conditions but the only runway may be closed for snow removal. Even in good weather, an aircraft may become disabled on a runway requiring you to hold or divert to another airport. Play it safe and always have an alternate and/or backup plan and carry extra fuel to ease the pressure of getting there.

Preflight Notes

While there are vast differences among types of aircraft, we cannot overemphasize how important it is to be familiar with the aircraft you are operating and the fine points of its fuel system. The sidebar on page 8, with detailed fuel system schematics, can help us understand how your airplane stores and distributes fuel to the engine(s).

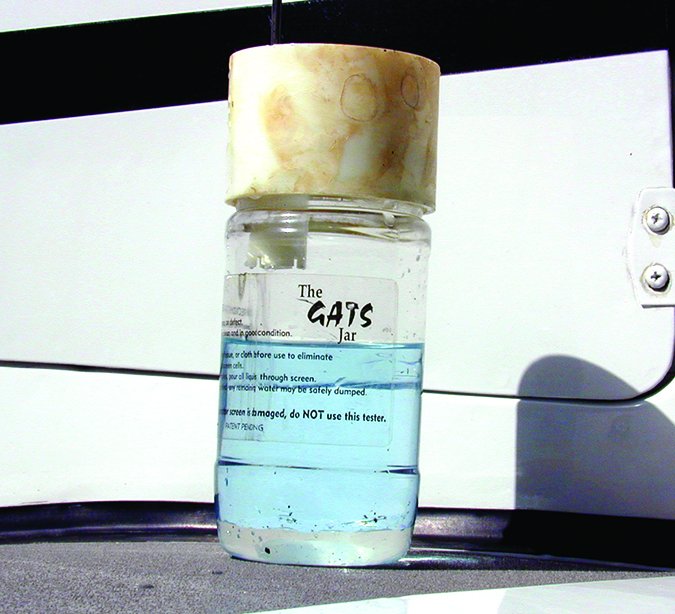

But there are some other basic information we all should know. For example, when checking fuel for contamination using a clear container, what should the sample look like. Is it the proper color for the grade of fuel required? Does the sample pass the smell test? Avgas mixed with other fuels (such as jet or diesel fuel) will not retain the proper color and requires further investigation prior to flight to prevent engine failure. Water in the fuel will settle to the bottom of the sampling cup, and often looks dirty—not something you want flowing to your engine.

With winter and associated cold weather, a frozen quick drain discovered on preflight is an indication of water in the fuel system. It needs to be cleared before flight. Ice crystals mixed with fuel can accumulate in fuel filters, impeding fuel flow causing fuel starvation during flight. Fuel vents are another item checked on preflight that must be free of obstructions such as bugs, mud, snow or ice. Blocked fuel vents can cause fuel starvation and engine failure.

Fuel caps should be checked not only for security but for any deficiencies such as cracked or missing gaskets, plus fuel stains on the wing aft of the fuel filler area indicating corrective action is necessary to resolve poor sealing. Fuel caps can be of the vented or non-vented type; always install a fuel cap with the type required for the exact application.

When filling fuel tanks to the maximum capacity on some aircraft, it’s necessary to ensure the aircraft is level. More than one accident has occurred when pilots “filled” their tanks on a sloping ramp and came up short at the end of the flight. In extreme situations, it may not be possible to completely fill the tanks.

And if that weren’t enough to worry about during your preflight preparations, some aircraft have special fuel draining procedures that must be followed. Fuel quantity indications for many general aviation aircraft are not very accurate, so a wise pilot will visually check the quantity of fuel in each tank. A calibrated fuel check rod or stick can be used to come up with a good estimate of the fuel quantity in each tank.

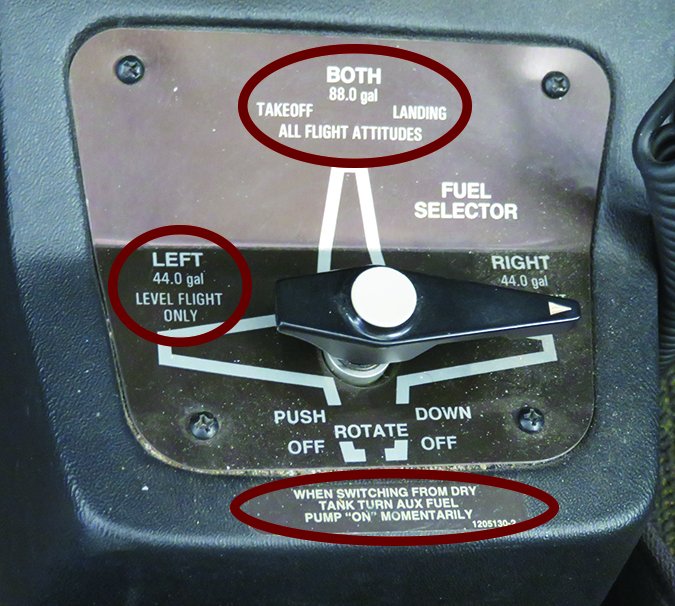

As part of your preflight action, you should ensure the fuel valve is free to operate in all of the intended positions, that the handle is tightly fitted to the shaft and that there are positive detents in each selected position. All aircraft must have a positive fuel shut-off position to be considered airworthy.

And don’t forget to check that the engine primer is locked closed after using it—fuel can be drawn through the primer valve and have a detrimental effect on fuel burn and associated range.

Operational Considerations

Spend some time studying the pilots operating handbook or flight manual to review the fuel system on the aircraft you fly and check the procedures concerning the fuel system. As aircraft become more complex, there are reasons why the fuel system is to be operated a certain way and the written procedures should always be followed.

Some questions specific to the aircraft you operate that you should be able to answer can include:

• What fuel tank position should be used for takeoff and landing?

• What is the usable fuel quantity for each fuel tank?

• Can you expect a center of gravity change as fuel is consumed?

• What is the ideal sequence of fuel tank usage to efficiently operate the aircraft?

• Can you use all the fuel in every fuel tank if I have an electrical system failure?

• What is the procedure to follow concerning the use of the auxiliary fuel pump? Is it to be on for takeoff, landing or only in an emergency?

• Is there any restriction on fuel tank unbalance during flight and during fueling?

• What should you do in the case of a fuel leak and where in the fuel system is the fuel shut off valve?

• Can you use auto fuel and, if so, what are the restrictions on its use according to an STC or other approval?

• Is there a minimum fuel quantity for takeoff?

Aircraft Fuel System Maintenance Issues

Proper maintenance of an aircraft fuel system helps ensure a continuous supply of clean, vapor-free fuel without leaks. As aircraft age and are used infrequently, fuel system components can fail. Flexible materials can become brittle and do not retain their designed elasticity, which can lead to leaks or complete failure. Fuel bladders, fuel pump or carburetor diaphragms, O-rings and flexible hoses all are subject to failure over time.

An important consideration is not only that leaks reduce the amount of fuel available. They also allow air or vapor to enter the fuel system. Fuel systems are designed to operate on liquid fuel, not vapor. Flexible fuel hoses are recommended to be replaced at five-year intervals and, while not mandatory for most privately operated aircraft, it certainly is a good idea to replace hoses that are no longer flexible or indicate signs of stress, cracking or heat damage. When replacing hoses, be sure to route the new one exactly as the one it replaces.

Fuel caps are another area of concern as a cap that leaks fuel externally can also allow water or other contaminants to enter the fuel supply. Some fuel caps are prone to leak and possibly can be replaced with an improved design.

No matter how simple the fuel system or how familiar with it you may think you are, it pays to review the system and procedures once in a while. Especially important is to thoroughly understand the system before operating an aircraft for the first time. Accidents relating to fuel can almost always be prevented by performing the preflight by the book and checking carefully for contamination, while ensuring there’s enough of it in the fuel tanks to safely complete your intended flight.

Mike Berry is a 17,000-hour airline transport pilot, is type-rated in the B727 and B757, and holds an A&P ticket with inspection authorization.