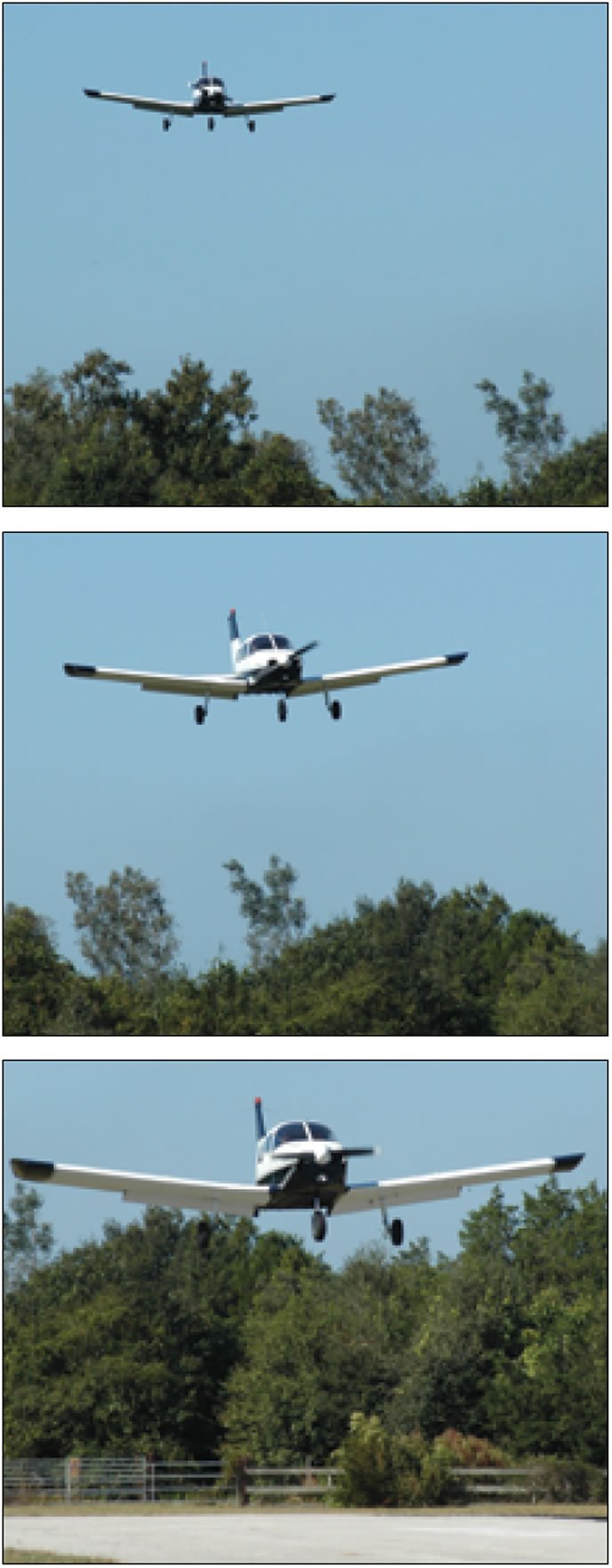

The ideal flare results from one continuous motion, beginning with raising the airplane’s slight nose-down attitude to arrest the descent, all the way through touchdown on the mains in a nose-high attitude. Few of us are that good—or that lucky—so we fall back to doing it in stages:

pitch slightly up to slow the descent rate and begin decelerating, wait for the effect to be known, then add more nose-up. Rinse, repeat. The timing and rapidity with which we pitch up the second time depends on everything that’s happened before on this approach: How high are you? How fast? How much power are you carrying into the flare? How heavy (or light) is the airplane? How stiff is the headwind you’re flying into, if any? Based on the answers to these questions, we’ll either add more nose-up input or hold what we’ve got. Then we do it again until establishing the desired nose-up pitch attitude, right above the runway at stall speed.

Unless we’re very high at this early stage of the flare, we should never lower the nose beyond a level attitude to descend to the runway. Doing so risks touching down first on the nosewheel, presuming your ride has one, but even if you’re herding a taildragger, you don’t want to lower the nose very much. Doing so changes the airplane’s trajectory back toward the runway; if you’re lucky, it’ll only bounce. If you’re not, it could be the first cycle of a pilot-induced oscillation, which is a whole ‘nuther topic.

Instead, a ballooning event—or simply pitching up too high—is better corrected by establishing a shallower pitch angle, usually done by relaxing nose-up pitch input and allow the airplane to continue decelerating.