We bow to no one in our willingness to reject ATC clearances and forcefully but politely seek what we want and need from a controller. Since our chair usually is moving faster than their’s, we cop the attitude that our needs are more important than ATC’s. At the same time, we certainly understand controllers often have little flexibility in responding to our needs, whether due to their own requirements, conflicting traffic we know nothing about or high workload.

288

But they also need things from us: basic airmanship, concise communication and the ability (willingness?) to follow instructions. To put it another way, both sides of the pilot/controller relationship have expectations. We know what ours are; What are their’s? To find out, we asked a controller-friend working in an ARTCC in the Midwest U.S. to share with us his top five pet peeves. Here’s what we learned.

Concise, Confident

Voice is the primary means with which pilots and ATC communicate. It’s an imperfect technology, except when compared to all the others, although the day is coming when pilots and ATC will simply text each other. Until then, we’re stuck using the existing VHF party line that is airborne communication. And, as with anything else, there are right and wrong ways to use it.

The Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM) agrees: “Radio communications are a critical link in the ATC system. The link can be a strong bond between pilot and controller or it can be broken with surprising speed and disastrous results.”

Just as if we’re speaking to someone in person or on a telephone, our inflection, cadence, what we have to say and the words we use all convey an image. When we’re dealing with ATC and, especially, want or need something, the image we project can have a lot to do with whether and when we get what we request. Again, the AIM: “All pilots will find the Pilot/Controller Glossary very helpful in learning what certain words or phrases mean. Good phraseology enhances safety and is the mark of a professional pilot. Jargon, chatter, and “CB” slang have no place in ATC communications.”

Our ARTCC controller also agrees. “Anytime you push that PTT button and speak, you should already know exactly what you’re about to say,” he told us. “Thinking on frequency or sounding uncertain slows everyone down.” In our experience, wasting time or sounding unprofessional often also is guaranteed to put you at the end of the line for service when you have a problem, question or request.

There is a flip side, of course. Frequently, controllers and pilots “think” they know what the other wants and expects, but it’s not always true. The sidebar on page 14 presents two common examples involving when to perform a course reversal before crossing a final approach fix inbound. In both instances, it appears the pilots were correct in their interpretation of the AIM, despite ATC’s expectations.

Situations like this have simple solutions: If you’re not sure, ask. That can be problematic when the frequency is jammed or you’ve already been handed off to the next controller from the one who cleared you.

Still, seeking clarification makes sense, according to our ARTCC controller: “But if you’re not sure what to say or are confused, don’t hesitate to ask for clarification. Controllers aren’t cops, but they definitely want to make sure you got it right and will usually welcome the inquiry.”

Readbacks, Callsigns

Any time the topic is communicating with ATC, issues with reading back clearances come up. Spend much time on a frequency, and it’s again apparent that voice communication in a party-line environment leaves something to be desired.

The issues associated with reading back clearances are well-understood. A summary of “readback” and “hearback” problems identified by analyzing what controllers and pilots themselves say about the problems is in the sidebar at right. As the analysis highlights, expectations—hearing what we want and expect to hear—can be a major problem on both sides of the mic.

“If a controller gives you a command, don’t abbreviate it any less than they did when they gave it to you. Everything is stated for a reason and we need to hear it all said back to us,” the ARTCC controller reminded us.

Of course, readbacks have two purposes. First and foremost is so ATC can verify the clearance was received. How many times have you heard a controller issue a clearance only to be greeted with…silence, forcing him or her to repeat it, slowly and firmly, eating up valuable time on the frequency. In extreme cases, the flight’s gone NORDO, of course, but most of the time it’s a matter of someone not paying attention.

But another reason for readbacks is what we’d call double-secret verification. By listening to the pilot’s readback, the controller can verify the correct information was transmitted. Added our ARTCC controller, “That’s not just so we know you got it right, but so we know that we said it correctly to you in the first place.”

A final point about communicating with ATC involves callsigns and duplication. Especially when operating near an airline hub, airline flight numbers and registration number-callsigns can get confused. A Cessna with a callsign ending in 152 easily can be mistaken for a Southwest 737 with the same flight number. And similar registration numbers—51E and 15E, for example—are easily confused. In our experience, ATC frequently notifies both aircraft on the frequency with similar callsigns to be alert for the challenges. That said, transposing callsign numbers happens with great regularity in our experience.

One solution comes courtesy of our ARTCC controller. “Also, don’t forget to include the ‘November’ in your tail number, even if the controller abbreviates it to the last three digits. Many airlines have three digit flight numbers, and the ‘November’ helps separate you from them,” he added.

Situational Awareness

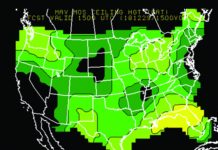

On numerous occasions, we’ve seen ATC issue us revised routings designed to keep us away from jet traffic descending into or climbing away from a busy hub. For example, cruising north- or southbound at or between 10-15,000 feet msl southeast of CLT is busy airspace. From experience, we know similar conflicts exist at similar locations and altitudes near any Bravo airspace in the U.S. We usually don’t like re-routings, but they’re a fact of life.

Even when—perhaps especially when—we’re VFR, ATC doesn’t like flibs to be there. We’re relatively slow, unpredictable and can be very difficult for jet crews to spot, even with their TCAS equipment.

“If you’re flying within 50 miles of a major airport (ORD, DFW, JFK, etc.) and below 15,000, keep your head on a swivel and eyes out the window looking for traffic. Staying out of the Class B airspace keeps you safe of Tracon’s traffic—mostly. But what many pilots don’t consider is the arriving and departing aircraft transitioning between Tracon and Center,” the ARTCC controller emphasized.

“These aircraft pass through arrival and departure ‘gates’ depicted on most terminal area charts. Whether you’re IFR or VFR, those are busy places to be if you’re just flying by.”

VFR Flight Following?

One way to ensure we stay out of the way of faster-moving traffic, at least when the weather allows it, is to go VFR but with ATC-provided flight following. Such thinking is heretical to those who go anywhere, everywhere, anytime in the IFR system (you know who you are…) but can be a real time- and fuel-saver when weather and airspace considerations allow it.

Of course, flight following is no guarantee ATC will point out all potential traffic, since it’s offered on a workload-permitting basis. Still it gets and keeps us in the system and simplifies things if we encounter IMC and need a clearance or our destination is within/under Bravo airspace.

A widespread perception among pilots is that flight following isn’t popular with controllers. Not so fast says our ARTCC controller. “Personally, I like it when I’m talking to the VFR aircraft that are in my airspace. There have been too many times where I have given airliners traffic calls for merging VFR aircraft that I have no idea what they’re doing. At least if I’m talking to the VFR aircraft, I will have a general idea of their flight plan, and I can give them a traffic call so they are at least aware of the merging aircraft.”

Just remember flight following is and will always be a workload-permitting service ATC offers. Don’t become dependant on it or complacent about nearby traffic. When it gets busy, ATC may or may not point out traffic conflicts for you. When it gets really busy, your service can be summarily terminated, leaving you no one to talk with even as you pedal full-speed toward active SUA or Bravo airspace.

Listen First, Then talk

As noted earlier, the party-line atmosphere of ATC communications has numerous drawbacks. But it also has some benefits, not least of which is the ability to grab the big picture involving traffic, weather and other operational challenges. Coming onto a new frequency after a handoff is one occasion when it pays to listen first, then use your microphone—if you don’t you easily can interrupt a conversation or even step on someone, earning everyone’s ire. Generally, it’s a bad idea to annoy ATC.

A great example of listening to gain information instead of outright asking for something involves ride reports. Even if you’re flying a flib IFR in what we call Indian Country—below, say, 8000 feet, where the Cherokees are—it’s likely you’ll be forced to listen to overhead airliners seeking and giving ride reports. Spend much time in the en route IFR environment over and near the U.S. Rocky Mountains and you’ll swear half of the communications you hear involve them. What’s going on?

Cabin service, for the most part: Airline crews want their customers to be free to move about the cabin but doing so in turbulence risks injuries and lawsuits. From an operational standpoint, however, knowing where the turbulence is and how strong it might be is useful information, even for a flib driver

“We as controllers understand that flying in bumpy air is no fun for you pilots and we will do what we can to keep you out of any turbulence,” our ARTCC source said. “If the frequency sounds busy, wait for a break in the chatter before asking for a current ride report. Sometimes while you wait you may even hear a relevant report given to another pilot along your route of flight, saving you a call.” The same is true regarding re-routes, weather avoidance and other operational issues confronting crews aboard aircraft of all sizes.

Thanks to technologies like GPS and advanced electronic instrumentation replacing steam gauges, operating personal aircraft in today’s IFR environment is arguably simpler and safer than ever before. Understanding how ATC works and what controllers expect goes a long way toward ensuring a smooth flight, with everyone on the same page throughout. Look for additional details on interacting with ATC in future issues.