The emergency locator transmitter, or ELT, has long been one of the most problematic devices regularly carried aboard general aviation aircraft. When first mandated in the early 1970s, there weren’t enough of them available to equip the fleet, and replacement parts and batteries were scarce. Nevertheless, the FAA was interpreting the law mandating them to mean an aircraft without a working ELT wasn’t airworthy. Hilarity ensued.

Those first ELTs, produced under FAA technical standard order (TSO) C91, failed to activate in a crash more than 75 percent of the time. When they did activate, according to AOPA, 97 percent of the time it was a false alarm. By 1985, when the FAA revised the standards and came up with TSO-C91a, a lot of the bugs had been worked out, but the ELT’s troubled history painted it with a mostly deserved reputation for unreliability. Those earlier devices still meet the FAA’s requirement to carry an ELT (see the sidebar on the bottom of the opposite page), but it perhaps is time they were retired in favor of newer technology.

Today, TSO-C126b is the current FAA benchmark for ELTs, having gone into effect in 2012. It’s a big improvement over earlier standards and increases the likelihood of the ELT itself remaining intact in an accident, thereby improving the chances pilots and their passengers will be located and rescued much more quickly than before. But that’s not all you need to know about ELTs.

False Alarms

As noted, false alarms have plagued ELTs since they were developed and mandated. In fact, they still occur, even with the latest standards. According to the FAA’s Information for Operators InFO 18007, released July 2, 2018, ELTs generated 8786 false alerts in the U.S. during 2017. The agency says the majority of 406 MHz ELT false alerts occur during testing and maintenance. There’s a reason for that.

Early, non-406 MHz ELTs are relatively easy to test during a required inspection: Wait until the first five minutes after the hour, then turn on the ELT and listen on a nearby receiver for the telltale sound for no more than three sweeps. If you heard the ELT’s audio output, the test is complete and the device passed. That kind of test isn’t appropriate for a 406 MHz ELT, however.

An ELT meeting TSO-C126x transmits a digital, encoded signal at much higher power than its older, analog predecessors. That signal is monitored by an array of satellites which can sense it more readily and alert authorities on the ground much more quickly than the old technology. In other words, even if you’re doing your test in a hangar and only allow one or two sweeps, search-and-rescue assets may still be alerted. That’s wasteful of resources and can endanger first responders. Instead, 406 MHz ELTs should only be tested in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Time To Upgrade?

When 406 MHz ELTs first hit the market, many in the U.S. felt it should be mandatory to replace those meeting older standards. The NTSB got involved, as did the Federal Communications Commission. Ultimately, Congress settled the issue by stating that older ELTs still satisfied the mandate to carry one. In 2012, meanwhile, the FAA canceled TSO-C91a, with the effect that no new 121.5 MHZ-only ELTs can be brought to market and only previously approved products may be bought or installed. Today, it’s rare to find an older ELT available for retail purchase.

There’s no doubt in our mind that 406 MHz ELTs are the better mousetrap. They transmit a higher-powered signal, identify the aircraft and owner, and can narrow a search area from 12-15 miles to yards. Their batteries last longer and most are designed to be easy, painless replacements for an installed, older ELT. The only real downside is the expense of buying and installing them. Is it time to upgrade? Absolutely. When your bird is in the avionics shop for ADS-B, have a 406 ELT installed. You won’t regret it.

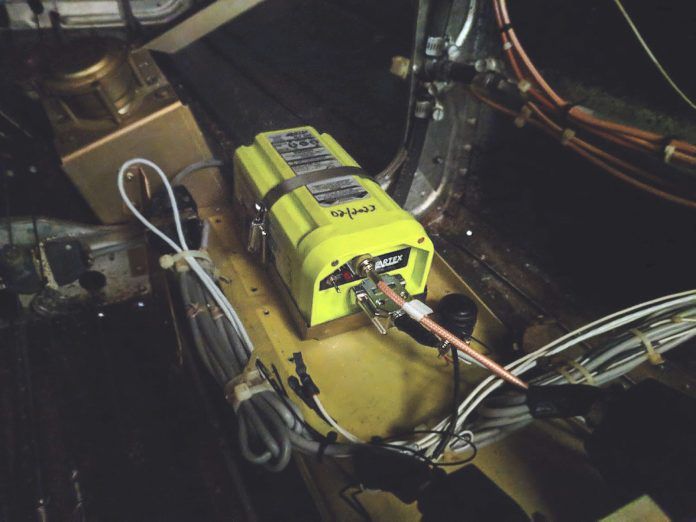

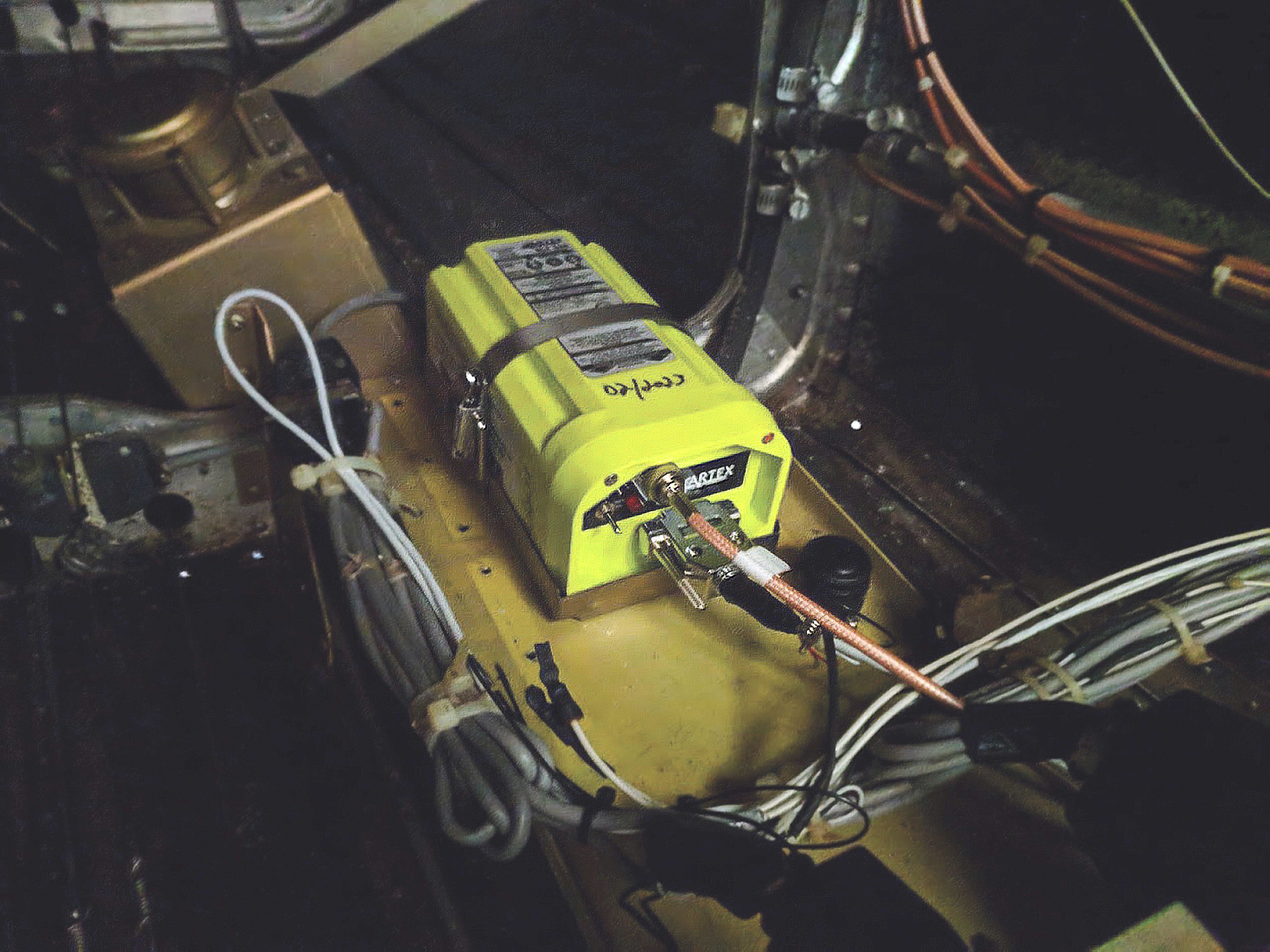

The Artex ELT 345, shown here installed in the tailcone of a Beech Debonair, is one of the latest ELTs on the market. It features easy retrofit installation, a long-life battery and a built-in GPS receiver to help pinpoint an accident site. It’s a 406 MHz device, though it also transmits on 121.5 MHz, in compliance with FAA TSO-C126b.

What’s An ELT?

The emergency locator transmitter is a mostly self-contained device engineered both to survive most aircraft accidents and, when triggered by deceleration forces, to begin transmitting a “whoop, whoop” audio signal (homing beacon) on 121.5 (and formerly on 243.0 MHz) MHz. Modern ELTs produced under TSO-C126x transmit a digitized signal including the beacon’s unique identification on 406 MHz and the non-digital audio signal on 121.5 MHz.

An ELT mainly consists of a G-switch to activate the device, a transmitter, an antenna and a battery to power the thing. If they’re not mounted within easy reach of the crew, ELTs usually are installed with a remote switch, allowing ON/OFF/ARMED/TEST functionality. They’re required to be tested/inspected during an annual inspection and their battery is to be replaced when 50 percent of its useful life has expired, as established by the manufacturer.

When Are You Not Required to Have an ELT?

The FAA’s FAR 91.207 is the rule on ELTs. It says every aircraft must have one, except when they’re exempt. And that list is lengthy. FAR 91.207 exempts:

– Scheduled flights by scheduled air carriers;

– Aircraft used in training operations within a 50-nm radius of the departure airport;

– Flight operations incident to aircraft design and testing;

– New aircraft prior to delivery;

– Aerial application operations;

– Aircraft certificated for research and development purposes;

– Aircraft used for showing compliance with regulations, crew training, exhibition, air racing or market surveys;

– Single-seat aircraft;

– For up to 90 days, when the ELT has been removed for inspection, repair, modification or replacement; and

– Aircraft with a maximum payload capacity of more than 18,000 pounds, when used in air transportation.

In other words, just about every aircraft is exempt from carrying an ELT except your basic Part 91 operator: you and me.