It’s that time of year again in the Northern Hemisphere, when the average cross-country flight is going to have to deal with thunderstorms. Where I live, in Florida, this time of year each mid-afternoon brings with it the rumble of thunder, usually followed by some hard rain, then cooler temperatures. That’s on the ground, of course.

Aloft is a different story, but predictable nonetheless. Even though Florida thunderstorms can be relatively benign when compared to the behemoths that march across the Great Plains in advance of cold fronts, they all feature torrential rain, icing, hail and airplane-shredding turbulence. They are to be avoided, if necessary by executing a 180-degree turn, landing before they arrive at your location or by circumnavigation. Period. How you handle thunderstorms depends greatly on the tools you have available—how you’re equipped. Generally, you’ll always have ATC and your Mk. 1, Mod. 1 eyeball, and that can be enough. A recent trip I flew highlighted for me how those and other tools can be used to avoid some relatively nasty weather but still get to your destination with unruffled feathers.

Planning

This wasn’t a pop-up trip—I had several days’ warning and knew that the time of day I wanted to fly—late afternoon—was the worst possible choice when it comes to thunderstorm avoidance. Still, my schedule dictated a late-afternoon launch. I’d have to make the best of the situation.

I did have a golden out: Wait until the afternoon’s thunderstorms died out along the route, then depart. That was my Plan B, and would have meant departing around dusk and arriving at my intended destination—KPDK, Atlanta, Ga.’s Dekalb-Peachtree Airport—well after dark. That wasn’t a logistical problem for this trip, but I did want to get there and get settled in. Plan C would have been to depart the following day early enough to make a first-thing-in-the-morning appointment.

The great thing about Plans B and C was that I could implement them at almost any time. How? By landing at the nearest airport, of which there were scores along my intended route.

And, since I had known about this upcoming trip, I started paying attention to relevant weather a few days ahead. Thankfully, there were no fronts or tropical weather approaching. If there had been, I would have considered additional options, like leaving a day early, or drastically altering my route. As it was, my planned route fell apart as soon as the wheels were in their wells.

Broken-Field running

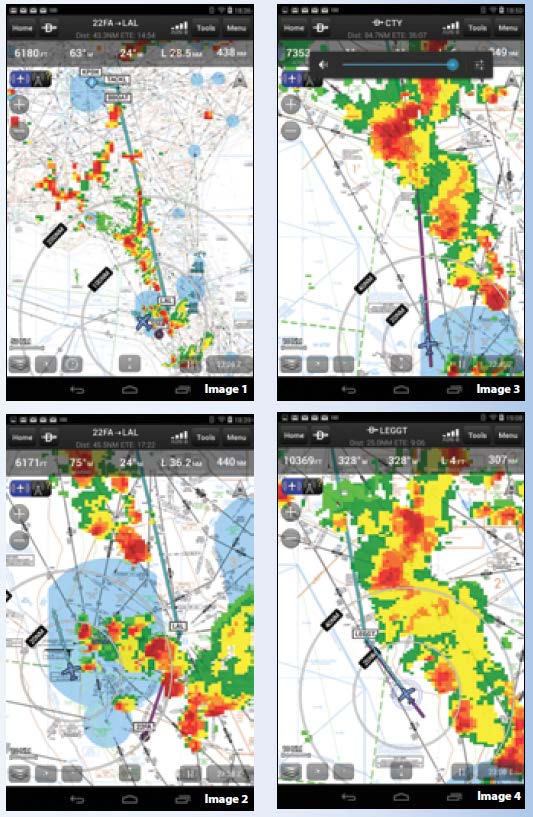

That route is depicted in Image 1, on the opposite page. Heading north out of the private strip where I base always means dealing with the Tampa Class B, and filing over Lakeland keeps me clear of that airspace. I’ve never seen that facility’s controllers fail to do everything they can to work with various flights, even FLIBs like me. This day was no exception.

Tampa Approach had its hands full, with an evening push and the weather. Going east meant coordinating with Miami Center, and probably sweeping around Orlando to the northeast. The good news is the storms weren’t moving quickly; in fact, they weren’t really changing much at all, either in intensity or size. (They were moving slowly west, toward the Gulf of Mexico, which isn’t normal thunderstorm movement elsewhere in the U.S.)

Their stability made them predictable, and easier to see and avoid. Ducking around to the west, out over the Gulf of Mexico, was the best option. This is relatively normal routing for IFR FLIBs moving up and down the coast in Tampa’s airspace. It took ATC a few minutes to work me into the local flow, but soon we both settled on a plan. Image 2 at right shows the airplane icon well within Tampa’s Class B and having turned the first big corner.

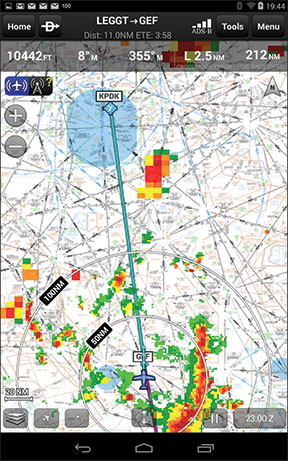

Eventually, Jacksonville Center worked out routings for me and everyone else in the sector that avoided the weather to the east, but put us out over the Gulf of Mexico. Initially, they had everyone going to the CTY (Cross City, Fla.) Vortac (Image 3) but quickly figured out that wasn’t going to work. Shortly, we were rerouted over LEGGT intersection, Image 4.

From there, things got better, and I motored the rest of the way to Atlanta with minimal deviations. Along the way, I tallied four different full-route clearances and two different transponder squawk codes.

Tactical or Strategic?

There’s long been an argument among pilots on whether Nexrad is a strategic or tactical tool in dealing with thunderstorms. The safest way to think about how to use Nexrad in the cockpit is strategically: Use its information to develop, implement and monitor a strategy for thunderstorm circumnavigation, from a distance. And that’s a solid way to use the data, especially since latency can make it some 20 minutes old by the time it appears on your in-cockpit screen. Meanwhile, the scene outside will have changed—sometimes significantly—in 20 minutes. But, yes, Nexrad also can be used tactically, just not by itself.

Ideally, of course, we wouldn’t be needing any of this in the first place: We’d either be at home watching it all on the Weather Channel or the skies between us and our destination would be clear and blue, with tailwinds. Since that’s not likely to happen all the time, at least to me, we need to develop tactics for dealing with thunderstorms. One of the first things to do is have multiple detection systems available, to ensure you don’t miss anything. On this flight I had three detection systems, not counting a panel-mounted Strike Finder (see above).

One of them is obvious from the images: In-cockpit Nexrad, courtesy of ADS-B IN. Its availability and utility really is what makes a flight like this easy and predictable in the first place. Airborne weather radar would be nice, but piston singles like mine typically can’t mount a large enough radar antenna to be useful in all situations. Airborne weather radar also can’t see 250 miles ahead, or to either side of the airplane, so Nexrad wins out on those features.

The second weather detection system I used on this flight was ATC. The men and women at the Tampa Tracon and Jax Center have seen all this before, and have substantial institutional and personal experience on how to make things work. Rather than try to vector flights through “weak spots” or inflexibly denying deviation requests, they tend to work proactively to reroute flights away from the weather. All of which is good.

The final thunderstorm detection and avoidance system I use is one referred to earlier: the Mk. 1, Mod. 1 eyeball. In fact, remaining visual with convective activity—i.e., not entering clouds or areas of reduced visibility when thunderstorms are about—is pretty much my Number One avoidance technique. Once you abandon the ability to see the storms, you also forfeit one of your best tools for avoiding them. In fact, the only real issue with visual thunderstorm avoidance is at night.

My bottom line on the tactical vs. strategic argument? First, it’s a silly argument, if for no other reason than there’s no clear point at which we cross the line from being strategic to being tactical. If we must draw a line, I’d suggest any kind of deviation from an on-course heading is tactical while rerouting and rescheduling a flight is a strategic move.

I’d also suggest the distinction is of little consequence, especially when the storms invade a terminal area encompassing your departure airport or destination. That’s when everything becomes tactical. While en route, at altitude and 100 miles away, you can think strategically. But at the end of the day, the argument boils down to the tools you have for detection and avoidance, and how you use them.

Air Mass Vs. Frontal

In my admittedly limited experience, there are two basic kinds of thunderstorms: those generated by frontal activity and those that aren’t. The latter kind are generally thought of as “air-mass” thunderstorms, meaning they get their energy from heating of the air mass instead of the temperature differences and lifting of air associated with a front or trough. Since both types can be extremely dangerous and always are to be avoided, it can be a distinction without a difference. But how you avoid them does differ.

For example, frontal storms usually are moving in lines or clusters, sometimes at 30 knots or more. Their movement helps them develop, and they can cover quite a bit of territory in an afternoon. That movement also is something you can use to your advantage: Don’t like where the storms are right now? Don’t worry; in an hour or so they won’t be there anymore. Delay your departure, or land, and wait them out. Then you can motor on your way.

But that very movement also can be a problem, especially when trying to avoid or circumnavigate them. Depending on what you’re flying, the storms easily could be moving at 50 percent or more of your groundspeed. Trying to circumnavigate them while flying into headwinds affords fewer options. Instead, try to get past them, then turn and use their own movement to help distance yourself from them.

Air-mass storms, on the other hand, can be almost stationary for hours at a time, especially in their dissipating stages. That makes them predictable, but also means they can park over your destination and make an on-time arrival problematic. When that happens, the solution isn’t rocket science: Wait them out.

The storms I was dealing with on this trip were the air-mass type, which are the most common over Florida in the summertime. They’re usually smaller and less violent than their frontal-variety cousins, but that doesn’t mean they’re any less dangerous. It does, however, mean they’re not moving quickly, so getting around them or keeping an appropriate distance isn’t that hard, even for a slow-moving FLIB.

The Bottom line

Even if you’re armed with only your eyeballs, you still have one of the best tools available for avoiding thunderstorms. Stay in visual conditions, orient yourself so you always have an out (a 90-degree or 180-degree turn, for example, toward a downwind divert airport with solid VFR) and simply refuse to fly through any clouds or visibility-reducing rain. If you must fly into a cloud or rain shaft, be absolutely sure you know what’s on the other side: Cloud formations in and near thunderstorms can magically be roughly the same color as blue sky, but you don’t want to go there.

Meanwhile, you probably have other tools available, including ATC. Use them, and benefit from the “big-picture” ATC can provide. These days, in-cockpit Nexrad probably is the gold standard when it comes to helping understand what’s going on around you. Airborne weather radar also is good, but requires skill and experience to interpret correctly, and still can’t “see” to either side of the plane.

Staying visual with thunderstorms always is your best option. If you do, you’ll never fly into one.

Sferics vs. Nexrad: The Sad, Awful Truth

My airplane had an Insight Instrument Corp. Strike Finder when I bought it. The unit has worked well, never required maintenance, and rarely fails to light up, as pictured at right, when thunderstorms are about. It’s called my attention to weather some 250 nm away but it’s also failed to alert me to too-close storms at night. On one memorable evening, I snuck up on a small storm off St. Augustine, Fla., which advertised its presence next to my right wing with a bolt of lightning. The Strike Finder showed nothing, unlike my shorts.

Sferic devices like the Strike Finder and competing Stormscope models work by detecting and plotting lightning strikes. They can discern the direction quite well; distance is difficult, however, because there’s no triangulation. So they guesstimate the distance based on strength of the lightning. Most of the time, they get it close enough.

But with either satellite-based or ADS-B IN-delivered Nexrad in the cockpit, an sferic device immediately shows its age. It never was a tactical tool: You don’t want to get up close and personal with a storm using an sferic device as your only detection tool because its resolution isn’t good enough. Compare the two images at right, which were captured at roughly the same time, and tell me which you’d prefer. It’s really no contest.

An sferic device does have one thing going for it, though: Its data is free. There are no subscriptions to forget renewing, no ground stations to fail and no need to re-boot if the software soils the bed. (Performing a reset via its circuit breaker has come in handy, however.)

In their day, sferic devices like the Strike Finder were valuable tools, but only offered a big-picture, “there be dragons” view of convective weather. We have better tools now.