In the beginning, airborne lightning detection was a bug, not a feature. Older radios, especially the automatic direction finder (ADF), tended to fall down when thunderstorms and associated lightning were about. Communications became filled with static and the ADF needle pointed to the lightning, not the desired station. Soon, enterprising pilots figured out the ADF was pointing at a dangerous part of the thunderstorm and used it as an avoidance tool, coarse though it was. Then, weather radar become small and light enough to routinely be fitted to transports, relegating the ADF to pointing at outer markers again.

Later, small, light and inexpensive thunderstorm detection devices known as sferics—the 3M Stormscope and Insight’s Strikefinder are examples—began finding their way into GA panels. The plotted azimuth was relatively accurate and an algorithm estimated range, giving pilots ample opportunity to detect storms along their route and divert if necessary. But the underlying technology used to detect lightning’s electrical discharge remained much as it was when the ADF needle was doing the work.

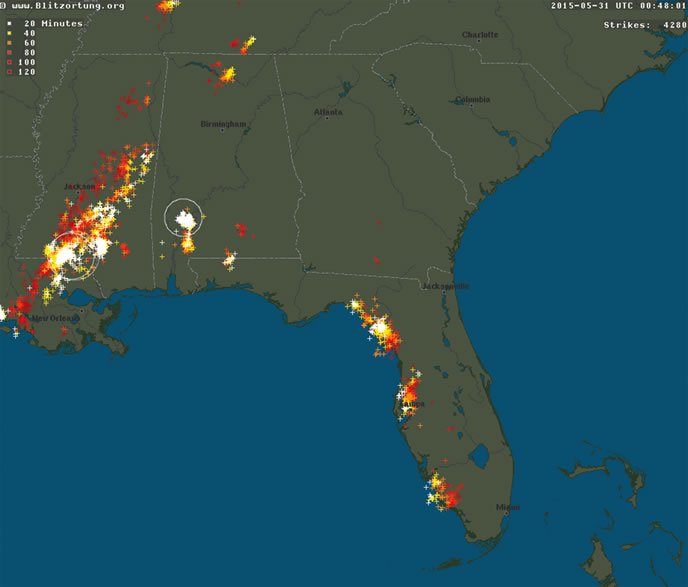

Thanks to today’s more sophisticated detection technology, pilots of even the lowliest piston single can access near-real-time lightning information and plot it on an electronic map overlaid with the flight’s course. It’s one of many tools—including the Mk. I, Mod. 1 eyeball and datalinked Nexrad weather radar—we can use to detect and avoid thunderstorms and the lightning giving them their name.