If nothing else, aviation is all about rationalization. The Wright Brothers thought it rational to abandon a lucrative bicycle business to leap off sand dunes in North Carolina; Lindbergh considered it perfectly sane to head for Paris without the benefits of GPS or even a windshield. And if you glance into the bathroom mirror, you may see the latest generation of flying dreamer look back. Thats good, because we need more romantics willing to grasp at whats wonderful simply for the pleasure of discovery.

The trick then becomes to rationalize this pursuit of flight into something practical so your family wont think you completely nuts. To do so requires that you weigh your anticipated pleasure against the often-overwhelming cost of aircraft ownership.

Once rationalized – and its up to you how thats handled – you need to consider just what youre trying to accomplish and how safely you can achieve your dream. But the first order of business is to please yourself.

Forget the spouse and kids and run away from well-meaning chums with their good advice. You dove into aviation because something grabbed at your soul and thrust you toward the clouds. There are 280 million people in this country and only about 600,000 are pilots, a more exclusive club is tough to find.

Feeding this aviation community is a wide range of aircraft with choices limited mainly by affordability. Unfortunately, as accident histories have shown us with devilish clarity, merely possessing financial ability doesnt translate into aviator savvy. If you can afford a Cessna 421 or brand-new Cirrus SR22, then you can also afford to attend Flight Safety for advanced individual training in your choice of high performance aircraft.

For many however, flight is a penny-scraping endeavor, the money vanishes faster than exhaust in the propwash. The temptation is to skimp on maintenance, training, or even flight itself. Sadly, those are three things that you shouldnt trim. The real savings are found in your choice of aircraft. For this article, well concentrate on the single-engine crowd.

What pilot doesnt dream of purchasing a new aircraft, fresh off the assembly line with a personalized registration number, a rack of Garmins, and that new leather smell? If you can afford the dream, go for it.

But perhaps that quarter-million dollars for a four-seat single could be better spent elsewhere. You could buy a new Husky A1B or American Champion two-seater with all the options for around $150,000 and save the other $100,000 for sales tax, hangar, and divorce lawyers. But if you base your aircraft selection solely on price, youre on the wrong path. You must first decide what your anticipated mission will be: Travel, excitement, or shameless machismo arrival factor? If you chose Travel, its time to examine your answer.

Four seats are a must for a decent traveling machine, right? Before you answer, apply the 3/4 Rule, which says that more than three-quarters of aircraft owners fly their four-seat aircraft with three of those seats unoccupied more than three-quarters of the time. In other words, too many seats cruise around fannyless. So, do you need a four-seater? If not, think smaller but not so small that you look silly.

Unless youre ready to devote your life to EAA, skip the homebuilts. Yes, you can find many cheap, single-seat mini-screamers on the used aircraft market. But, remember that when you buy a homebuilt, youre on your own. The designer is probably dead, deranged, or bankrupt, and the builder isnt named Cessna with a toll-free number for advice.

Instead, its a guy named Ed in Nebraska, who spent 12 years welding and gluing in his garage and after scaring himself half to death on the test flight decided to sell. If you choose the used homebuilt market think, caveat emptor.

Youre better off with used production aircraft, and your insurance agent might agree. That said, my first airplane was a homebuilt-it was fun to fly and cheap to fix after I broke the gear off on the first landing.

A four-seat airplane is usually roomy and comfortable and if you prefer the legroom, the longer cabin is great. Plus, you can buy a four-seater and remove the rear seats to create a truly useful hauling machine. Have your mechanic delete the seats from the weight and balance sheet and you may be able to convince your insurance company to lower your liability costs – fewer seats lowers exposure to dead passengers suing.

Assuming you cant visit your Raytheon dealer for a new $700,000 Bonanza, you can find an array of used production four-seaters ranging in price from $30,000 to, well, anywhere, frankly, but lets cap the upper end at $150,000. Somewhere in there is a used four-seater with a decent set of avionics. For the dollar-conscious youll be looking at antiques or classics and whatever you get will require constant attention and sharp flying skills.

Familiar Can Be Simpler

Familiar names such as Cessna, Piper, and Beechcraft are common among the lower-priced aircraft. The Cessna 172 is the most ubiquitous, and you cant beat the venerable spamcan for reliability and factory support. Just about anything beats it in speed, but for economy, 172s are proven. Now choose the model.

Roughly divided the 172s fall into two groups – those with Lycoming engines and the older models equipped with six-cylinder Continentals. Which is better? Its a question of personal taste and myth. Lycomings are reliable four-bangers – with annoying oil pump ADs – that can be repaired anywhere in the world. Parts are readily available. Personally, I love the smooth sound of the six-cylinder Continental and wouldnt hesitate to buy one.

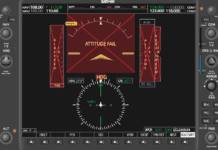

The major difference between the older and newer 172s is in the airframe. A 1950s Cessna looks and feels old. The panel does not conform to modern instrument layout, expect gauges and radios to be scattered helter-skelter. For serious instrument flying put your sights on the newer models.

Older models had manual flaps, a sloped cowling, and you sit a little taller in the seat – all features I like. The difference in flying characteristics between the older and newer models isnt enough to declare one better than the other. Both are 172s. Both go slow and work well from short fields. Neither will scare away your insurance agent. Old Cherokees are like old 172s: common, reliable, reasonably priced. Both are easy to fly.

Now take that docile 172, remove the nose wheel, and put it under the tail where it belongs. Youve crossed over to the dark side of taildragger flying where myth thrives on ignorance, and ignorance of how a tailwheel aircraft works will cost you a bundle.

Time was real airplanes sat with their noses pointed toward the sky, and tails sat on the ground. Then, someone made them ugly and easy to fly by installing a nosewheel. By shifting the CG forward of the mains the airplane became a bit more docile on the ground and generations of pilots have thrived without any exposure to tailwheeling.

Fine, but to limit yourself to tricycle geared airplanes is to restrict your personal growth and miss some bargains. If that sounds like rationalizing, it is, to a point.

Those of us who fly tail wheels do so because we love them. Generally speaking, they are trickier than nosewheels, but so what? One of the points of flying is to expand horizons, not to find a safe niche and quietly molder. So, rediscover that grab-at-the-clouds feeling and check out the possibilities in such four-seat tailwheel classics as: Cessna 170, 180, 195, Maule, Stinson, or the Piper Pacers and Clippers.

This group comes with a range of powerplants from the smaller Franklins, Lycomings, and Continentals up to the 260 and 300-hp radial Jacobs on the 195. Let your heart decide which one calls to you but be aware that the larger tailwheel classics, such as the Cessna 195 are real brutes to move around the hangar. Think smaller to the more modern Cessna 180 – essentially a tailwheel 182 – and you have a fast, heavy-hauling, four-seater that commands a good price.

Cessna 170s are bargains. You can find a good IFR-equipped 170A for $40,000. Theyre not fast, but they are graceful and easy to fly. Maules are everywhere. Avoid the Franklins unless you really enjoy working on rare engines. The same applies to the smaller Stinsons. Maules are loosely considered STOL, but performance is often in the mind of the seller.

Still, Maules are simple and sound – although somewhat homely (especially the tricycle versions) – four-five seaters that can be had at a reasonable price. The staff at Maule factory in Moultrie, Georgia is extremely friendly and helpful.

Alternatives to the Maules are the short-winged Pipers – Pacer and Clipper. If you dont like tailwheels, consider the Tri-Pacer; theyre increasing in value but still good bargains. Both the Clipper and Pacer are quick, economical four-seaters wherein passenger comfort was never a design consideration.

Both are delights to fly. The Clipper has joysticks while the Pacer was upgraded with control yokes. Neither had much in the way of instrument panel space.

Two-seat tailwheel airplanes abound. From Piper J-3 Cubs, Vagabonds and Cruisers through Luscombes, Taylorcrafts, Interstate Cadets, Porterfield, Aeroncas, and into the older Citabrias, the buyer has serious homework to do before plunking down cash.

Economy is the game here. While Piper Cubs are eternally overpriced – you can get better performance and more comfort in an Aeronca 7AC at half the price – this group is the entry level for the antique and classic airplane enthusiasts. Despite being built between 1941 and the early 1960s, these airplanes have readily available parts.

Although you can buy an old Taylorcraft, Porterfield, or Luscombe relatively cheaply and maintain it without too many tears, these older tailwheel airplanes demand solid flying skills. Theyll bite you in the wallet if you dont fly them correctly.

Thats the bad news. The good news is theyre not hard to learn. Sadly, finding a good tailwheel instructor is tough. Until a few years ago I enjoyed teaching tailwheel, but when Avemco unceremoniously bailed out of the commercial insurance market, many small time operators couldnt survive. Who got screwed? You, the pilot stepping up to tailwheels.

There are still flight instructors giving dual but you may not find one at your local airport, plus you really wont know if the instructor you hire is competent until he snatches a bad landing away from you in time to save the wing tips.

You cant learn to fly tailwheel from any article, and when you buy your dream tailwheel classic you must remember why the FAA issued you feet. If youve been lazy on the rudders for the past 20 years of flying a Cherokee, then be prepared to re-awaken your feet to coordinated flight before you feel comfortable with a tailwheel.

Old airplanes demand respect for the basic elements of flight. Their fuel systems are often convoluted, making it easy to run a tank dry at inopportune moments. You may have to learn to hand-prop to start the engine. Instrument panels are rarely in line with todays IFR scan, and amenities such as cabin heat, ventilation, and adjustable seats are the stuff dreams are made of.

Older airplanes are often uncomfortable, noisy, and cantankerous. You may have your head turned by a low-priced older Bonanza only to discover that while its fast and a delight on the controls, it can be a maintenance hog that gobbles up parts with new Bonanza prices.

One of the overlooked high-performance classics is the Navion. Made by several manufacturers over the years, it vaguely (real vaguely) resembles the P-51 Mustang – and could cost about as much to maintain. Navions are stout airplanes that ride turbulence beautifully and are so easy to land its embarrassing. But when you look for a mechanic to work on it, make sure hes a member of the local plumbers and steam fitters union and can handle all the hydraulic plumbing in these birds.

A third bargain in this high-performance group is the Bellanca Viking. You may be attracted by the low initial purchase price of a 300-hp retract, but these hand-crafted wood, steel, and fabric beauties can be nightmares if they havent been properly maintained.

Classic airplanes demand advanced skills from both pilot and mechanic. Many have wood spars. Great stuff, trees. Theyre strong, easy to shape, and bend instead of fatigue. They also crack and rot.

Both imperfections are easy to hide, so bring along your magnifying glass and a mechanic who knows wood. The problem is that such a mechanic is tough to find.

New spars, or spar materials, are available from several sources such as Aircraft Spruce (877-477-7823) or Safe Air Repair (507-373-7129). One IA mechanic who knows old wood-and-fabric airplanes is Tom Burmeister, owner of Return To Service (515-961-4787).

Nice Threads

Many older airplanes are fabric-covered. Originally cotton, most have been recovered in some form of polyester fabric. Forget the baloney sales pitches about lifelong fabric. All fabric wears out and needs to be replaced. Twenty years is about the limit, less time if its been parked outdoors.

Recovering an airplane is not that tough, anymore than dry-walling your kitchen is hard. Doing a good job however, takes talent and many expensive hours of labor. If youre paying a shop to recover an airplane, plan to spend a bundle. Some shops will encourage you to help with the grunt work such as sanding or stripping paint. It saves you money and gives you an appreciation for the process. Is an aluminum skin better than fabric? No. Aluminum corrodes and fabric rots; take your choice.

A thorough pre-buy inspection by a knowledgeable mechanic might save you grief down the road. And while youre in the pre-buy process be sure to do a title search. For around $75 several firms can dig through the FAA records to uncover any 50-year-old liens on your dream machine.

Dont be surprised to find old airplanes with incomplete logbooks. Things get lost over the decades. Finally, when looking for your dream machine if you see the phrase Mechanic Owned, realize that it means nothing. If you see the phrase No Damage History (or NDH), laugh and assume that every old airplane has had damage, especially tailwheel types. No damage history means it just isnt logged.

When you turn to the classics and antiques you set off on an adventure that requires your active participation. The factory that made your 60-year-old airplane probably went belly-up years ago. New Piper doesnt like the old Pipers. Cessna might not have the part you need for your new Cessna 195.

Luckily, there are good type clubs for most classic airplanes, an incomplete list includes: The Cessna 120/140 or 170 clubs, Short Wing Piper Club, Comanche Society, American Bonanza Society, and the National Aeronca Association. An Internet search will unearth gobs of others. Or join the Antique Airplane Association (641-938-2773) to gain access to a central source of information on the lot.

Whatever you decide – four seats or two seats, tailwheel or nose gear – search for the airplane that meets your dreams and then do your homework to see if its reasonable to maintain and insure. Find a qualified instructor to get you through the transition.

And, finally, when all the logical steps are complete itll be up to you to decide just how to rationalize your choice. My guess? It wont matter, because youll be in love and theres nothing rational about that.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Concealed Reality.”

-by Paul Berge

Paul Berge owns a 1946 Aeronca Champ and, perhaps ironically, is editor of Aviation Safetys sister publication, IFR.