Most IFR operations don’t require an alternate airport. That’s because the advertised weather often is better than required to select one and list it in a flight plan. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t at least have something in mind as an alternative place to land if, say, some nummy lands gear-up at your destination or, as we saw in December 2017, an entire major airport finds itself without power.

For those occasions when an alternate is required, there are some rules that apply. And some of those rules are directed at the equipment we carry or the planned destination. Although this isn’t that complicated, there are a couple of ways to screw it up. Deciding whether we need an alternate is where we start.

When We need An Alternate

There are two basic scenarios in which we need to select and file an alternate airport. The easy one is, well, easy: If your filed destination does not have a published (standard) or special (unpublished but available to you) approach procedure, you must file an alternate when submitting your IFR flight plan. That’s because of the way the pertinent regulation (FAR 91.167, fuel requirements for flight in IFR conditions), is written. If the destination doesn’t have an approach, we must file an alternate, full stop.

If the destination airport does have an approach, we need to research the forecast weather. That should be part of our preflight planning, anyway, so that part’s not hard. What may be difficult, however, is parsing the weather data. Helpful hints can be found in the so-called 1-2-3 rule, explained in greater detail in the sidebar below.

If the destination has approved weather reporting, read and understand it, along with the forecast, then act accordingly. If there’s no weather reporting, you may use “appropriate weather reports or weather forecasts, or a combination of them,” per the FAR. In effect, this means we can use the area forecast, recently replaced in the contiguous 48 U.S. states by the graphical area forecast.

Alternate Minimums

Presuming we’ll need to file an alternate due to the weather forecast, hang on to that Duat session for a bit longer: Our next task is using available weather information to ensure our chosen alternate airport is a legal alternate. To be a legal alternate, the airport must meet the criteria specified in FAR 91.169, as detailed in the sidebar above. But that’s not the full story.

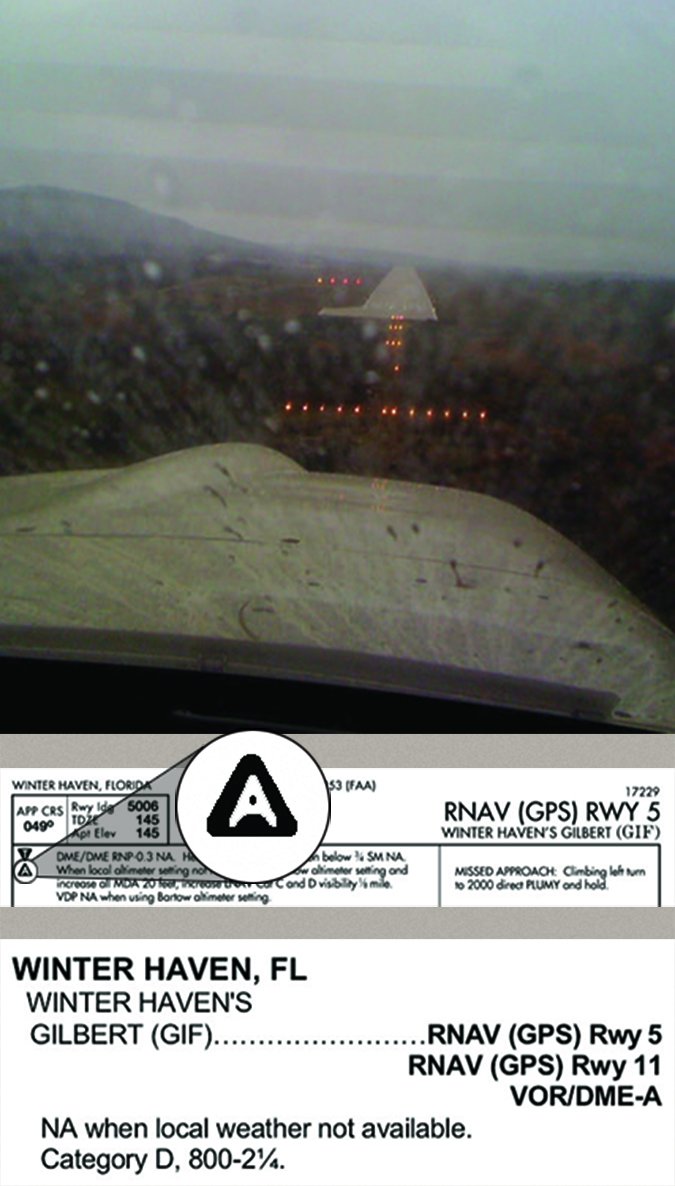

The second bullet in the sidebar above hints at the reality: Many airports and the approach procedures serving them have alternate minimums different from the 600/800 ceiling and two miles of visibility specified in FAR 91.169, or other conditions with which you must comply are imposed. The approach procedure excerpts at right give an example, involving local weather reporting.

Note that the RNAV (GPS) Rwy 05 procedure at Winter Haven’s Gilbert Airport (KGIF) in Winter Haven, Fla., carries the triangular symbol with an “A” in it, denoting a different set of alternate minimums exist. Diving into the alternate minimums portion of our favorite terminal procedures publication, we find the entry for Winter Haven. In this instance, presuming we’re not approaching in a Category D airplane, the only restriction to filing Winter Haven as an alternate is that doing so is not authorized when the airport’s local weather reporting system is not available.

The GPS Catch

A final note about GPS. A new policy adopted by the FAA in 2013 did away with prohibiting a plan to fly a GPS approach procedure at an alternate airport. Under the old rule, you could fly halfway across the country, miss a GPS approach and navigate to your alternate with GPS but you couldn’t plan to shoot a GPS approach. In fact, that’s still the case—the catch, if you will—but there’s a difference.

The new policy allows planning to shoot a GPS procedure at the original destination or at the alternate, but not both. The key word here is “plan.” As long as the plan includes a destination and/or an alternate airport served by a non-GPS approach your airplane is equipped to use, you can file the alternate. Once you get to the alternate, executing a GPS approach—even if you just missed one at Plan A International—is legal.

The 1-2-3 Rule—Other than helicopters

The so-called “1-2-3 rule” is part of FAR 91.167. Presuming weather at the planned destination (“the first airport of intended landing”) meets the 1-2-3 rule, no alternate is necessary. Let’s unpack this.

• First, it’s important to remember that the rule is based on “appropriate weather reports or weather forecasts, or a combination of them.” If the destination does not feature approved weather reporting, then the area forecast may be used. Note that the text-based area forecast (FA) has been replaced by the graphical area forecast product.

• 1: “For at least 1 hour before and for 1 hour after the estimated time of arrival….” This is fairly straightforward. Whatever your ETA is, if the forecast an hour before and an hour after doesn’t meet the “2-3” portion of the rule, you need to file an alternate.

• 2: “…the ceiling will be at least 2000 feet above the airport elevation….” Using the appropriate weather forecast, the ceiling (broken or overcast) must be at least 2000 feet.

• 3: “…and the visibility will be at least 3 statute miles.” Should be self-explanatory, but the same weather data used to determine timing and ceiling is used here as well.

IFR Alternate Airport Weather Minimums—Other Than Helicopters

Subsection (c) of FAR 91.169, IFR flight plan: information required, determines what weather forecast must be available before naming a destination airport as an alternate when one is required. Here’s what it says:

• To be a legal alternate, “appropriate weather reports or weather forecasts, or a combination of them, indicate that, at the estimated time of arrival at the alternate airport, the ceiling and visibility at that airport will be at or above the following weather minima:”

• “The alternate airport minima specified in that procedure, or if none are specified the following standard approach minima”

• For a precision approach procedure (ILS, GCA): Ceiling 600 feet and visibility of two statute miles.

• For a nonprecision approach procedure (LPV, LNAV, VOR, etc.): Ceiling 800 feet and visibility of two statute miles.

• “If no instrument approach procedure has been published…for the alternate airport, the ceiling and visibility minima are those allowing descent from the MEA, approach, and landing under basic VFR.”

Two Alternates?

Is one alternate enough? The FARs require only one, and it must meet the criteria outlined in the two sidebars here and as discussed in this article’s main text. But that doesn’t mean we have to go to the alternate if our original plan soils the bed. For one thing, if we have the fuel, we can turn around and go back where we came. We also can pop into the nearby VFR-only field that’s closer to our ultimate destination. Or we can go somewhere else entirely.

The rules on IFR alternates merely require that we consider an alternate airport meeting the described criteria. We don’t have to go there.