Back in the day, the formal risk management techniques applying to contemporary general aviation hadn’t been invented yet, so most pilots were on their own. How did they survive? Here are the main factors the author attributes to his success.

Flight Planning

I am a planner. As I began using GA airplanes for more and more of my travel, I found I needed to begin the flight planning process about 10 days ahead of time to avoid cancellations. Tending to the airplane’s maintenance needs, trip logistics and, above all, the rolling 10-day weather forecast were crucial to making schedule. If the weather trend was really poor for flying a non-ice protected airplane, I had time to make an airline reservation or reschedule meetings.

Caution

I became a chicken. I tended to add extra margins to almost any threat situation, even when a proper risk analysis would have shown I added excessive protection. Like most of us who had no formal risk management training, I learned this the hard way early on, as a result of situations like scud-running, flying in icing conditions and other “unwanted adventures,” as my friends John and Martha King would say.

Flexibility

I adapted to conditions. It was not unusual for me to leave on a Sunday or even a Saturday, rather than Monday, when the long-range weather forecast indicated the approach of a deep winter low or other no-go condition. I would also add hundreds of miles to the trip route at the drop of a hat, if it allowed me to avoid weather, fly in smooth air or avoid other hassles.

Technology

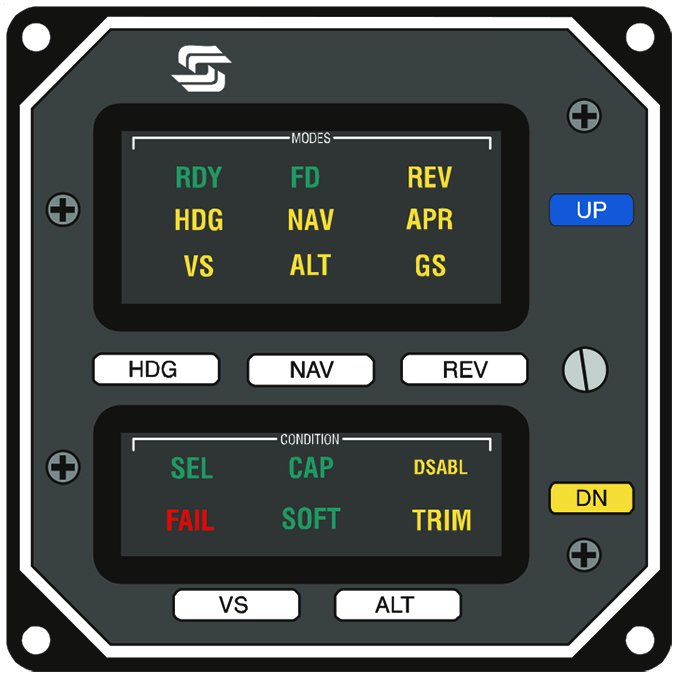

Ongoing conversations about automation certainly affirms that it can be a double-edged sword. However, I wouldn’t own or fly a high-performance GA airplane without an autopilot. I had them on the Mooney and both Bonanzas and they are both essential safety tools and range extenders, by greatly reducing fatigue. I was also among the first to use graphic weather devices in the cockpit, in an FAA test program in the mid-1990s. Given my abundance of caution, the weather devices mostly added to my utility, but I will also make the case that they have become important safety features on new and old aircraft.

Discipline

Your best intentions are only as good as your willingness to carry them out. Your ability to conduct effective risk management and safe flight operations depends on good, timely decisions at the tactical level. In 52 years of flying, I can only recall a few instances where stick-and-rudder skill was influential in saving the day or avoiding risk. The majority of those instances occurred while I was giving instruction and the student was unintentionally trying to kill us. In the few instances where I applied stick-and-rudder prowess, it usually was because I made a bad decision or still hadn’t learned the nuances of effective risk management.

If all of the above points sound suspiciously like sound, effective risk management, it’s because they are. It’s just that it took me a large part of the past 52 years to realize that I was using crude risk management all along.