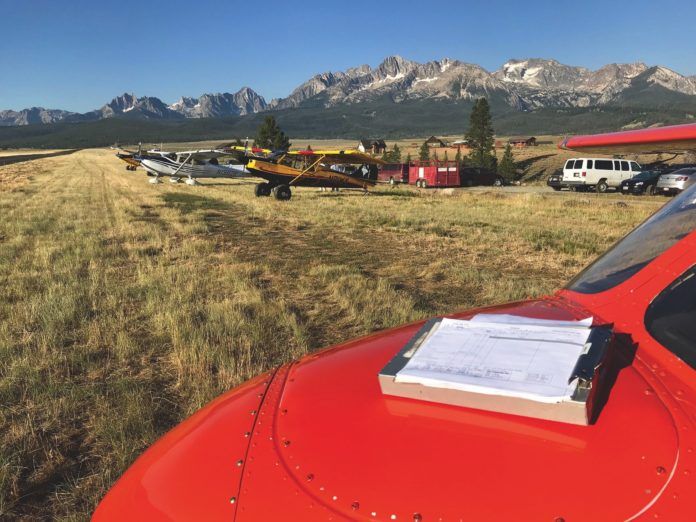

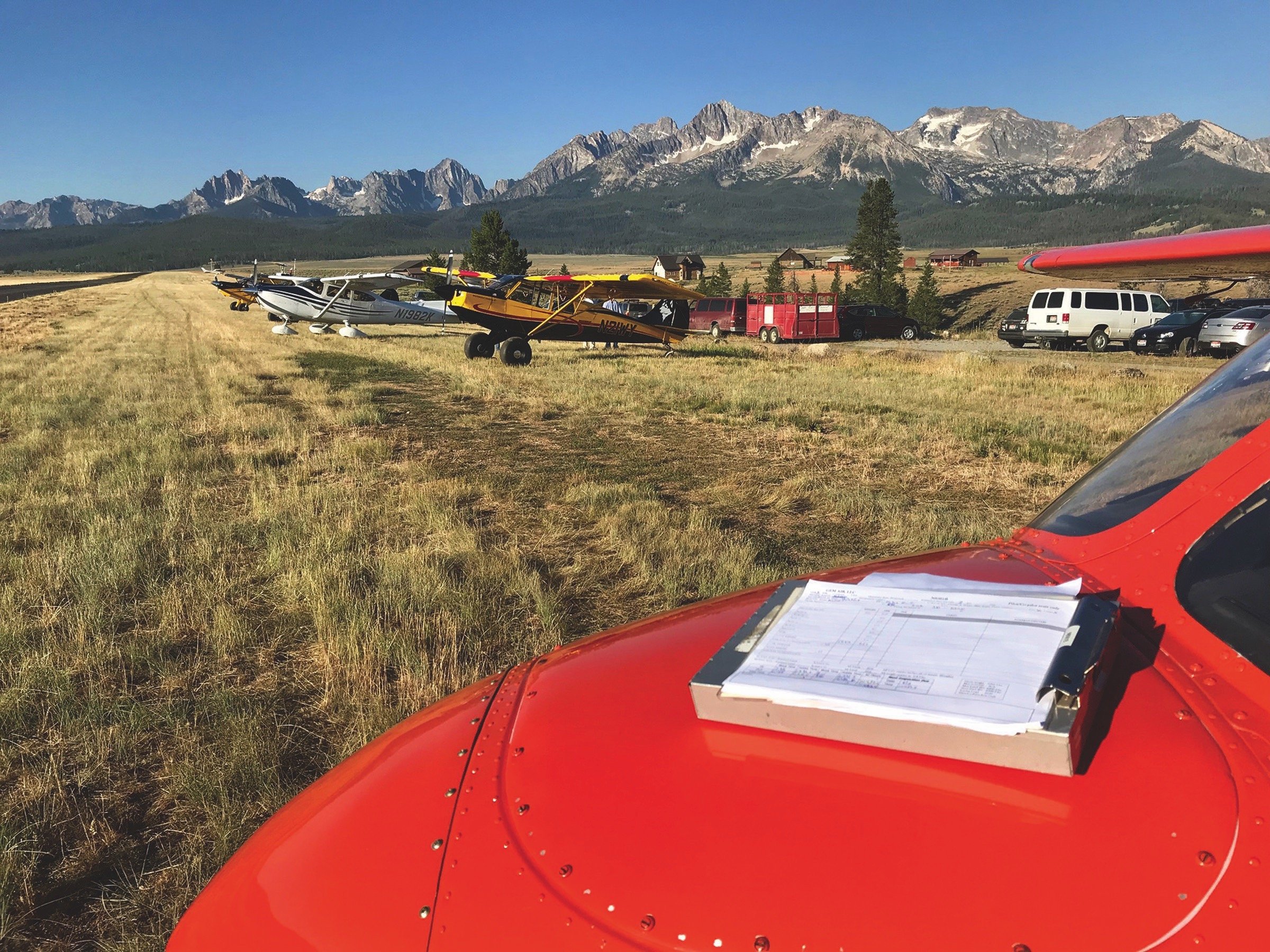

Thanks for Mike Hart’s article on all the goings-on in the backcountry flying environment (“Backcountry Safety Culture,” September 2018). I knew pilots engaged in flying those areas were a tight-knit group but I had no idea how organized their culture seems to be, and how important active communication is to reliable flight operations in rural, mountainous areas.

How can pilots flying over more-forgiving terrain and in busier airspace adopt some of these techniques?

Bruce Klaine

Via email

Good question! As you noted, communication is key. The good news in busier airspace is it usually results in a greater ATC presence. To maximize your communications, that means listening to the frequency and understanding what’s going on with the weather, with the number of aircraft headed for the same airport and with the traffic around you. Listening is a skill pilots don’t use enough.Another communication tool is the FBO’s pilot lounge or coffee pot. While a lot of what you hear around them will be propwash, occasionally you can pick up some real nuggets of solid information, especially once you figure out who to listen to closely and who to discount. Those of us with a life may find it inconvenient to spend all our free time at the FBO, so think about different ways of socializing with local pilots, including online forums, FAASTeam events, EAA chapters and other opportunities.

Required Maneuvers

I appreciate David Jack Kenny’s take on the value of keeping up with performance and ground-reference maneuvers after the checkride (“Maneuvers,” September 2018). I’ve found that they definitely help me to build confidence when I’ve been out of the left seat for a while, and can quickly restore the “feel” of the airplane. The same is true when confronting an unfamiliar type or when assessing skills of a new pilot-acquaintance.

One question: How can I self-assess the quality of my maneuvers without an instructor aboard critiquing me? How do I know I’m doing them correctly when I’m by myself?

David Aaron

Via email

One answer the old-timers might give you is, “If you’re not doing them right, you’ll know.” But that’s rather dismissive. Without being in the airplane with you, we can only suggest a complete understanding of the maneuver, what it’s used to achieve/demonstrate and how it’s evaluated. The relevant ACS document and its performance tolerances, plus referring to appropriate training materials during the planning process, should be enough. For confirmation, schedule a ride with your instructor.

Smart Than Direct

Your August article on IFR routings (“Smarter Than Direct,” by Tom Turner) highlighted for me the need to perform more flight planning than simply drawing a line in my EFB from my departure airport to the destination, filing “direct” and accepting whatever comes back from ATC in the way of a clearance. A couple of questions:

How can I know what approach to expect at my destination? And how much faith should I put into the FAA’s list of preferred routes or those generated by an EFB?

Thanks in advance!

Alan Gentry

Via email

As Tom described in his article, picking the approach you’ll be using before even taking off is directly related to the weather and a host of other variables. For example, you’re more likely to get it right on a short hop within the same facility’s airspace than you are on an hours-long cross-country. That said, having a good grip on the weather you can expect and the approaches available well before beginning the descent gets you halfway there. What else do you have to do with your time while cruising at altitude?Controllers always like it when you have a clear idea of your desired approach and communicate it to them early, perhaps with a request to fly directly to an initial approach fix. You can always use your ADS-B In weather and traffic tools to check the weather and surface winds at the destination and to watch as arrivals fly the approach in use.