There’s no question cockpit automation has made pilots’ lives easier. Moving maps, autopilots, GPS and automatic sequencing have altered the ways we humans ensure precise navigation and aircraft operation. The attraction is simple: Twirling a knob and pushing the right button at the right time usually requires less effort than hand-flying, especially during a gnarly approach. But there’s no free lunch.

One of the downsides of automation is that the pilot often is removed from the control feedback loop. In other words, he or she isn’t sensing what the airplane’s control feedback is saying. When manually making a certain control input, the pilot receives instant feedback—through the control system and the instruments—on whether the airplane is responding as expected. All that is lost when Otto is flying, even though the instruments may tell us everything is nominal.

When ATC or the airplane itself throws us a curve, we may not be ready to take control. Even if we are, punching off the autopilot can present an airplane significantly out of trim, or heavy with a coat of ice, something we would have noticed and resolved if we had been hand-flying in the first place.

Another downside of automation is we may forget that not everything in the panel is tied together: Just because we tell our magic panel to take the airplane around doesn’t mean it’s all-knowing and all-capable. We might still have to add power, retract landing gear and/or flaps, and manually drive through at least the initial maneuvering required to change the airplane’s trajectory. And the worse the weather, the greater the temptation to let Otto do it.

We’ll never know for certain if that’s what happened in the accident we’re about to look at. But it all adds up.

History

On February 4, 2015, at 1930 Central time, a Piper PA-46-500TP Malibu Meridian collided with a television tower guy wire and terrain near Lubbock, Texas. The solo private pilot was fatally injured and the airplane was destroyed. Instrument conditions prevailed; an IFR flight plan had been filed and the airplane was operating under an appropriate clearance.

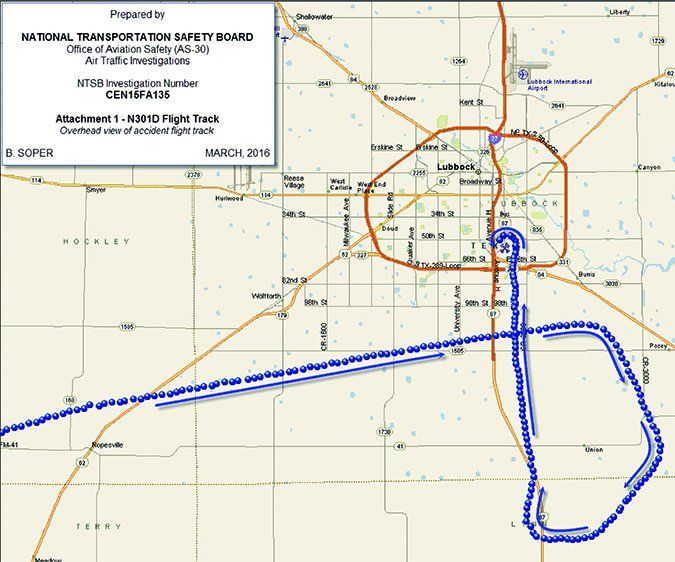

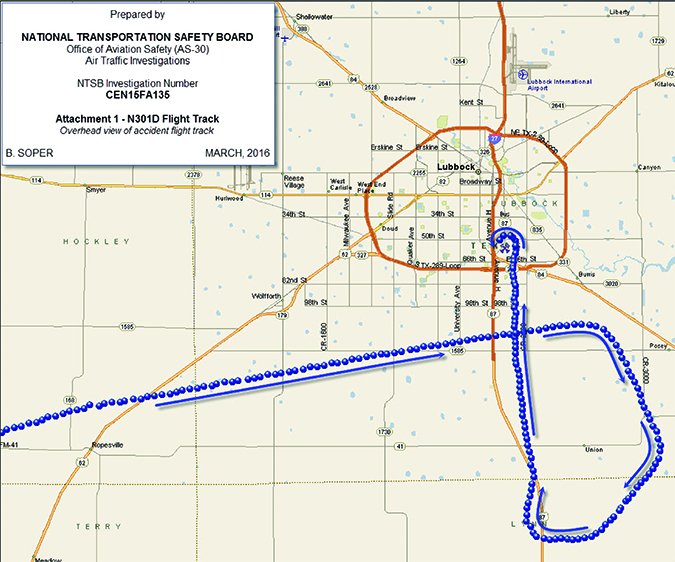

The pilot was executing the RNAV (GPS) Y instrument approach to Runway 35L at the Lubbock Preston Smith International Airport (LBB), and was about 10 miles south of the facility. The controller canceled the pilot’s approach clearance for spacing and issued a heading change off of the approach course. The airplane started a left climbing turn and then descended. It was lost from radar and attempts to contact the pilot were unsuccessful.

Investigation

Seventeen minutes after the accident, a special weather observation at LBB reported wind from 040 degrees at 18 knots, gusting to 27 knots. Visibility was seven miles, under an overcast 700 feet agl. Surface temperature was 28 degrees F, with a dewpoint of 25 degrees. The facility recorded peak winds from 030 degrees at 31 knots.

Prior to the accident, a pilot report (Pirep) was issued for moderate rime ice at 5200 feet msl, or 1918 feet agl, about 10 miles south of the airport. The pilot acknowledged receipt of this report. There was no history of the pilot contacting Flight Service on the date of the accident.

Earlier, at 1918, the pilot reported he was having a little trouble getting set up for the approach and wanted to circle until he could get things worked out. At 1921, the pilot requested a turn to the south, direct to the approach’s initial fix.

By 1925, ATC cleared the flight for the approach but the pilot had “trouble understanding the remainder of the controller’s instructions.” At 1929:29 ATC cancelled the accident pilot’s approach clearance for traffic and instructed the pilot to climb to 7000 feet and fly a heading of 275 degrees for re-sequencing. The pilot acknowledged and then confirmed the turn, which the controller amended to 270 degrees.

After ATC cancelled the approach and vectored the flight to turn west, radar data indicate the airplane began a left climbing turn from 5600 to 5800 feet msl. The turn continued through the assigned heading. The airplane then descended rapidly. The final recorded radar return showed the airplane at 5100 feet msl, or about 1900 feet agl. Surveillance videos from two different locations showed the airplane in a steep descent prior to striking the television tower, which was 814 feet tall.

The fuselage came to rest upright on a general heading of west. A propeller blade tip separated and exhibited scoring consistent with contact with a metal wire. The propeller nose cone displayed striations consistent with a large gauge wire similar to the downed guy wire. Post-accident examination found no evidence of structural icing on the airplane and no signs of ice were reported by first responders. There were no pre-impact anomalies which would have precluded the engine from producing rated power prior to the accident.

Probable Cause

The NTSB determined the probable cause(s) of this accident to include: “The pilot’s loss of airplane control due to spatial disorientation and light ice accumulation while operating in night, instrument meteorological conditions with gusting wind.”

The airplane was equipped with Garmin G500 flight displays, two Garmin GTN750 touchscreen navigators and an upgraded S-Tec 1500 autopilot computer. Earlier in the flight, the pilot requested delaying turns while he set up his panel to execute the approach, perhaps signifying he wasn’t proficient with his equipment, although it had been installed more than three years earlier. The pilot also had difficulty reading back the approach clearance.

There’s never a good reason for a perfectly good aircraft to enter what appears to be a spiralling turn and descend until it hits something. Although first responders did not notice ice adhering to the airframe, any accumulation could have been broken loose during the accident sequence. Reconfiguring an iced-up airplane for a go-around may have been too much for this pilot, especially if he didn’t know it had picked up ice.

I suspect the pilot kept the airplane on autopilot, changed the heading bug and commanded a climb. Ultimately, it could be the pilot simply forgot to add power while transitioning into the go-around, a climbing left turn, and the airplane flew itself into an iced-up stall. Bottom line? The pilot likely wasn’t in the feedback loop and couldn’t recover quickly enough.

AIRCRAFT PROFILE: Piper PA-46-500TP Malibu Meridian

Engine: P&WC PT6A-42A

Empty weight: 3436 lbs.

Max gross to weight: 5092 lbs.

Typical cruise speed: 250 KTAS

Standard fuel capacity: 170 gal.

Service Ceiling: 30,000 ft.

Range: 1000 nm

Vso: 60 KIAS