The U.S. air traffic control system is a living, breathing thing, one borne from necessity. As the system has matured, new procedures and technologies have been implemented, and many of those developments have impacted our cockpits. Even so, the men and women who staff the ATC system today perform many of the same basic tasks their predecessors tackled 50 or more years ago.

288

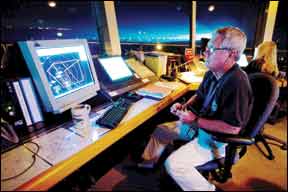

Air traffic continues to grow—the airlines are doing okay, even as GA activity remains relatively flat—so plans are in place for even greater system automation, the Next Generation Air Transportation System, or NextGen. Meanwhile, the controller workforce also is undergoing changes, some of them self-inflicted, but all of them having an impact in our cockpits. Generally, the controller you work with has less experience and time on the job than ever before. The average controller’s experience level isn’t likely to change much in the near future, which has implications for safety—yours and mine.

Defining The Problem

More and more these days I’m feeling like one of aviation’s little old ladies. It’s not my creaky knees when I step up on the wing of my airplane that’s convincing me. Instead, it’s that little glance to the left we pilots all take when we step on an airliner, especially a commuter airliner, peeking into the cockpit, our own comfort zone, just to see who is up there. More often than not who I see these days are a pair of kids hardly older than my own and, well, the flight instructor in me starts to wonder…who was their flight instructor, and what did she teach them? And…was it enough to conduct the flight safely?

Fortunately, I don’t fly commercially that often. Most of the time I take the big step up onto the wing of my own bird, and then slide into the much more comfortable front left seat. I operate out of an uncontrolled airstrip, but often venture into crowded Class C and B airspace, and into IFR conditions. Eventually, I’ve got to talk to someone, and—yep, you know where I’m going with this—about the time I hear the ATC voice respond back with non-standard phraseology or an absurd command, I get that queasy feeling again, just like on the airliner, and I wonder, hey kid, how long have you been at this? And, do you have any idea what it’s like up here, how my aircraft works and what it (and I) can do?

I’m not alone. An airline friend of mine related a recent outtake from the Los Angeles Tracon: Airliners are routinely asked to fly a looped departure out of LAX, climbing to cross the vortac climbing through 10,000 feet. Apparently the young controller on duty was so stymied by a Lufthansa heavy jet’s refusal of the clearance that he refused the refusal, blurting out on the frequency, “Oh come on; Southwest can do it!” Perhaps he wasn’t taught the not-so-subtle performance difference between a Boeing 737 loaded with enough fuel for Las Vegas versus a fully-loaded 747 bound non-stop for Frankfurt.

Now, I’m perfectly willing to give anyone, any day, his or her due, age regardless. Ours is a skills-based industry and if you’ve got the moxie and the skill you can stay, but aviation is notoriously unforgiving of incompetence or even just inattention, and when I detect either from a green pilot or air traffic controller, well, then the educator and safety advocate in me gets all fired up.

And if it happens when I’m sharing airspace with them? I’ll argue if I can. I’m not afraid of the very standard term “unable,” either. And once I’m on the ground then I whip out the computer and file a NASA form with the Aviation Safety Reporting Service (ASRS). Perhaps I’m earning my little old lady stripes, after all.

A friend tried to tell me all of this was just an age-ist fantasy, so I went on the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Web site and looked it up. Turns out, we’ve been churning through air traffic controllers in this country recently. In the past four years, the U.S. government has hired upwards of 5000 new controllers. That’s better than a quarter of the entire cadre of ATC workers. It also translates into that same proportion of the ATC workforce having less than four years’ on-the-job experience. Oh, and it takes at least three years to produce a fully qualified controller, according to the FAA. Another call to an old friend, a retired FAA controller now working as an ATC safety inspector, confirmed that the turnover of practically the entire working FAA air traffic controller staff is imminent. Why?

ATC History 101

Let’s have a quick poll and a short history lesson. How many readers were flying in 1981? I was. Yep. I was working on my instrument rating. And then President Reagan got into a labor dispute with the air traffic controllers, who were unionized. He said they could not strike. He said that if they struck, he’d fire them all. And then they did. And he did. And it was not a fun time to be trying to fly IFR in the U.S. Supervisors ran the towers and Tracons on skeleton staff. Demand for ATC services far outstripped the supply, so much so the agency put in place a general aviation reservation system, GAR, which required non-scheduled operations to obtain a slot for their proposed flight a day or so ahead of time. It was similar to the traffic management programs in place today for special events, but applied to all U.S. airspace.

Reagan, true to his word, did not rehire a single controller who participated in the walk-out. Instead of rehiring seasoned veterans, we raised a whole new crop of air traffic controllers right from scratch. More than 10,000. And it was hard, dangerous work for pilots, all of us. Within two years I had two near misses, both while on instrument approaches. And both my airplane and the other aircraft were operating in radar coverage, on IFR clearances. Pilots had to listen up, and you better believe that we learned to look outside the cockpit, even when in the clouds.

288

In that time period, however, we employed some great IFR shortcuts that were labor-saving for both pilots and air traffic controllers. Tower-to-tower IFR clearances—known as tower en route, or TEC—became common, as did “cruise” clearances, allowing a pilot the discretion of starting his descent and approach without further input from ATC when traffic was light and the destination was uncontrolled.

How about the “VFR-on-top” clearance, allowing pilots to provide their own separation from traffic and fly VFR altitudes while in VFR conditions, on an IFR clearance, above the clouds. That gave IFR pilots “direct” navigation long before /G and GPS-direct clearances became de rigueur.

Deja Vu All Over Again?

Thirty years have passed. Air traffic controllers must retire from active controlling at age 56, and can retire with full benefits anytime after 25 years of service (or 20 years of service and 50 years of age). National Air Traffic Controllers Association (NATCA) President Paul Rinaldi said in a speech last year to his membership that, “When the current fiscal year began, more than one in six controllers was eligible to retire. By 2014, 25 percent of the workforce will join them in becoming eligible to retire.”

The result? Some days I swear I think I’m back in 1982, trying desperately not to spit nails while explaining again to clearance delivery that I want my clearance before I start my engine so that I don’t have to sit there, burning expensive avgas, while he searches the system for it, or telling him that there really is a clearance he can issue that just gets me through the fog layer (called an IFR-to-VFR clearance; it contains the classic line “if not on-top by 2000 then….”).

The government insists that NextGen will lower the workload of both controllers and pilots, which will allow ATC staffing to drop without endangering lives. But if NextGen doesn’t materialize, or doesn’t materialize on time…yeah, you get where I’m going with this.

Some Good News

My recent research did uncover some good news. Rinaldi says, “Experienced controllers are electing to stay on the job longer to improve the safety of the system and to safely develop and deploy NextGen. These veterans are also working with and teaching the more-than-4000 trainees, passing along their experiences and wisdom.” The association also is working hard on its own to welcome and nurture the newest controllers, with its NATCA Reloaded program. The program provides a contact person for the fledgling at each designated ATC facility, as well as a Web site and social network for these newbies to hook up and support each other. “We try to reach them while they are still at the Academy in Oklahoma City,” says Garth Koleszar, the national training representative for NATCA. “We are also creating a professional standards program for air traffic controllers, in collaboration with FAA, and already have 14 professional standards committees staffed. We’ve developed an ATC code of conduct. And we hope to have classes for young controllers in professional standards in the 31 collegiate ATC programs around the country, and at the academy,” he says. “Peer-to-peer training on professionalism is really the best path to facilitating change.”

NATCA was also key in renegotiating and restarting the FAA Fly-a-Controller program, which provides ATC with limited jumpseat privileges throughout the USA. The program, started in 1998, was discontinued after September 11, 2001, citing security concerns. It was known for having had controllers who abused the program, using it as a way to fly the system for free. Today’s program is much tighter in its execution, according to Koleszar. “We’re really a team—the air controllers and the pilots. It’s critical for ATC to understand that,” says Koleszar. To date, more than 40 ATC have shared a cockpit with airline pilots in the system. That’s hardly a dent, but then, the new program is barely a month old as of this writing.

Fly Defensively

How can you make a difference? Double-check your clearances to make sure they make sense, and refuse those that simply don’t. Yes, this will take longer. Yes, it will slow down your trip. It may also save your life. And if you feel hassled? Wronged, even? File an ASRS NASA form at asrs.arc.nasa.gov right away. Explain the issue. ATC will get the message, and you’ll protect yourself from FAA enforcement in case the controller decides the issue was you, and files a report.

If you’ve got the time and the inclination, don’t be afraid to offer a controller a ride, as well. It certainly won’t hurt for him or her to discover what the world (and his requests) look like from inside your cockpit. You might learn a few things, too!

Like the controllers themselves, we’ll probably have to have a little patience as things get rolling, and give them time to understand life from our side of the radarscope. In the meantime, watch your back.

Amy Laboda is a freelance writer, CFII-MEI and a National Lead FAAst Team representative. She holds an ATP and flies two experimental aircraft, one that’s sweet and slow, and one that’s pretty and fast.