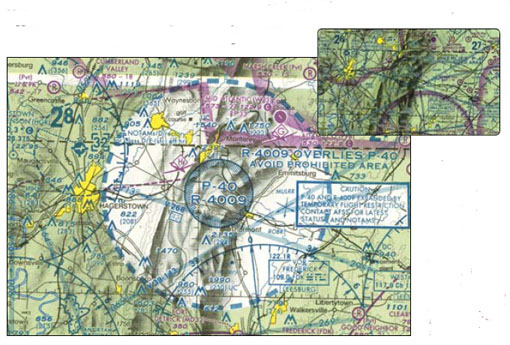

The word “airspace” is a relative newcomer to our lexicon, and when first coined in the early years of the previous century probably seemed suspiciously redundant, not to mention anathema to the individualists of the era. Times have certainly changed since then, and our national airspace system has gotten more complicated. Given the “mission creep” so characteristic of todays bureaucracies, we can presume the rules under which we fly will not revert back to being less restrictive. With all the exposure given to airspace security and inadvertent entries into temporarily restricted airspace, this is a good time to review the various types of Special Use Airspace, otherwise known by the autocratic acronym SUA, with an emphasis on the different ways they are charted. Whats So Special About It? What is SUA? Its any airspace of defined dimensions, having a base and (in most instances) an upper altitude wherein activities must be confined because of their characteristics or wherein limitations may be imposed upon aircraft operations that are not a part of those activities. (There is always going to be a base, by the way, but not always a ceiling: For example, the area to the east of the Kennedy Space Center has no upper limit.) There are about a half-dozen types of “formally defined” SUA, which are summarized in the sidebar on the opposite page. From a bureaucrats viewpoint, there are basically two types of SUA: regulatory (in the sense they are defined by formal rulemaking) and non-regulatory. Prohibited Areas and Restricted Areas (as well as Class A, B, C, D and E airspace) are regulatory. These two regulatory SUAs are implemented by FAR Part 73, but MOAs, Warning Areas, Alert Areas and controlled firing areas (CFAs) are non-regulatory. Special use airspace (except CFAs) are charted on Sectional and en route charts and descriptions include hours of operation, altitudes, and the controlling agency. In addition, Military Training Routes (MTRs) certainly qualify as special use, although they arent officially considered SUA. (Anything moving at 400 knots within 1500 feet agl qualifies as “special” in our book.) There are also two other types. If you fly within an Air Defense Identification Zone, or ADIZ, which is usually along coastal waters, you get to file a flight plan that isnt VFR or IFR, but Defense VFR, or DVFR. We lucky souls in the Washington, D.C., area get to file an ADIZ flight plan. For the offshore version, you need to file periodic position reports and identify yourself before returning to or entering domestic airspace. Otherwise, you might have a new wingman sporting all kinds of neat pyrotechnics. In Alaska, these areas are known as Distant Early Warning Identification Zones, or by the acronym DEWIZ. 388 Prohibited Areas First, lets talk about the oft-dreaded Prohibited Area. Although over half of the currently 10 or so separate parcels of fixed and charted prohibited airspace are presidential in some way, not all are. Theres the Pantex nuclear assembly plant in Amarillo, Texas, home of P-47, and the Boundary Waters Canoe Area in northern Minnesota, where youll find P-204, P-205 and P-206. Then theres the relatively new P-50 over the U.S. Navys submarine base in Kings Bay, Ga., with its newest sibling, P-51 (still in gestation at this writing), brewing over another submarine base in Bangor, Wash. 388 Someone is sure to point out that any Temporary Flight Restriction (TFR), which wed hear about via a Notam, can invoke a prohibited area, at any time and anywhere, and thats true. If President Bush threw out the opening pitch in Yankee Stadium, you can bet there would be one in place in the Bronx that day. Restricted Areas The second most common-and the other type of “regulatory” SUA-is the Restricted Area. Like most other SUA, they are marked on VFR charts by blue “combed” boundaries. Unauthorized entry can be bad for your health, although ATC will allow IFR and VFR flights to use an inactive Restricted Area without any specific clearance through it. An identifying number (such as R-4009, which is associated with P-40 and charted on the opposite page) will be listed near or within the area. A listing on the bottom of the aeronautical chart identifies the area by number and indicates the location of the area, its altitude limits, times of use and the name of the controlling agency. Unlike Prohibited Areas, Restricted Areas usually have specific hours of operation. Referring again to the chart excerpt on the opposite page, did you notice how two Victor Airways V268 and V39) go right through R-4009? If you looked on an IFR chart youd see that the Minimum Enroute Altitude (MEA) for V268 is 5000 feet MSL. Well, R-4009 extends from 5000 feet up to and including 12,500 feet. First, just because V268 goes through R-4009 doesnt mean you can automatically go through it whenever you want. Second, a VFR pilot on V268 below 5000 feet would actually be inside P-40, and even if an IFR pilot did legally traverse R-4009 along V268, say if he flew east right at 5000 feet, it wouldnt take much to get him in hot water, as you might imagine. Military Operations Areas As you may have noticed from perusing your various charts, MOAs are the most prevalent and widespread type of SUA. They consist of airspace of defined vertical and lateral limits established for the purpose (as they say) of separating “certain military training activities” from IFR traffic. By definition, a MOA can exist from the surface up to 17,999 feet. (Anything starting at FL180 up in Class A is known as an “ATCAA” or Air Traffic Control Assigned Airspace.) Whenever one is in use, IFR flights may be cleared through it if ATC can provide separation. Practically, however, ATC rarely exercises this option and will usually route IFR traffic around it. Pilots operating under VFR should exercise extreme caution while flying within a “hot” MOA. Contact the local AFSS to get the latest information, and prior to entering an active MOA, contact the controlling agency for traffic advisories. Dont forget that most military aircraft are painted in a low-visibility camouflaged paint scheme or color, which only makes them more difficult to see-even for each other-at any time. Although they are using on-board sensors as well as their eyeballs to watch for traffic, things happen very, very quickly for the military pilot and they may miss seeing you. If you see one military aircraft, keep looking! Its quite likely that one or more additional aircraft are in the vicinity. Alert And Warning Areas Alert Areas are depicted on aeronautical charts to inform nonparticipating pilots of areas that may contain a high volume of pilot training or an unusual type of aerial activity. The biggest difference between this type and a MOA is that all parties involved must obey “the FARs.” Warning Areas may contain hazards to nonparticipating aircraft in international airspace, though most military operations in these areas are not weapons related. A Warning Area is the least restrictive of the various classifications. Military Training Routes Now if you thought that was all, there are still more. Military Training Routes may be associated with a MOA. To be proficient, the military services train in a wide variety of airborne combat methods. One phase of this training involves “low level” tactics and MTRs have been designated in an attempt to let everyone know where these operations might occur. There are a few nuances, though. One is that charting of MTRs leaves something to be desired, since they can be up to 55 miles wide in some parts of the U.S. The sidebar on the opposite page goes into more detail. By the way, if I ran NACO, Id see to it that these MTRs had additional charted data; instead of just “VR1754” Id like to see something like “VR1754 7N/10S 100-1300 AGL.” Other Stuff There are other types of routes that may also be encountered. They are SR (Slow Routes) and LATN (Low Altitude Tactical Navigation Areas). Slow Routes are designed for use at or below 1500 feet agl, with airspeeds at or below 250 knots. There are about 200 of them. The LATN areas are different in that they have specific boundaries. They can extend to 1500 agl, with bases down to 300 feet agl, and are flown at speeds not to exceed 250 knots. They are designed to allow crews to practice tactical navigation and flying in areas of simulated and varied threat potential, without being limited to flying a standardized, published route. Sadly, LATNs are not published on aeronautical charts. Some other military airspace structures include National Security Areas (shown by a broken magenta line, in which avoidance is voluntary, but strongly advised); Cruise Missile Routes (or “unmanned aerospace vehicle routes;” youd see them near Los Angeles and around Florida); and Aerial Refueling Routes (of which there are about 100). Finally, even though Instrument-rated pilots are less likely to run afoul of SUA, we all must keep track of where we are and where were going. That includes not only the directions in which we choose to fly, but complying with where ATC says we must fly (or taxi), as well as adherence to assigned altitudes. Not all busts involve airspace, after all; a significant portion involve deviations from an ATC clearance.