By the time you read this, it’ll be late September or early October. In some regions of the U.S., that means leaves changing color, frost on the pumpkin and winterizing the house, the vehicles and the airplane. In other regions, like where I am, it means shutting off the air conditioning, opening the windows and putting a final close cut on the yard. Cooler, better flying weather, along with some seasonal challenges, likely will confront us all soon.

For many, it may mean installing a winterization kit on the airplane’s engine, to help keep the oil and cylinders warm at low power settings. It also could mean installing new door or window gaskets to keep out the coming cold air, or even switching floats for skis. For those parking their airplane outside, it may also mean a few trips to the airport to sweep off snow before it freezes and hardens, making removal more of a chore.

Around here, I haven’t had to block off some of my oil cooler in recent winters, and the airplane resides in its own hangar. If I head north over the winter—why?—I have some covers and plugs that will keep the engine and cabin clear of snow. Not so much the wings and tail, however. Instead, the major aviation challenge I’ll likely face this winter in Florida will be the influx of additional traffic as snowbirds and vacationers shrug off the cold.

In addition to airplane storage and preparation, the actual conditions under which we fly may also change. The good news is the air will be colder and denser, enhancing performance, even though we’re wearing warmer clothing and have stashed some heavy coats in the back. It’s not likely your weight and balance will be affected, but you never know.

The bad news is that colder air will place us closer to temperatures at which airframe ice may form. It also means frozen precipitation—snow, sleet/ice and freezing rain—conditions for which few personal airplanes are well-equipped.

From my experience, that first winter trip of the season can be magical, especially if there’s snow on the ground illuminated by a full moon. It can also be a rude awakening to discover icing at an altitude too warm for it only weeks before. So it might be a good idea to take an extra minute or two when planning your first few flights this season to give icing and other winter weather considerations some thought. By April, you’ll be a pro.

The PAFI Debacle

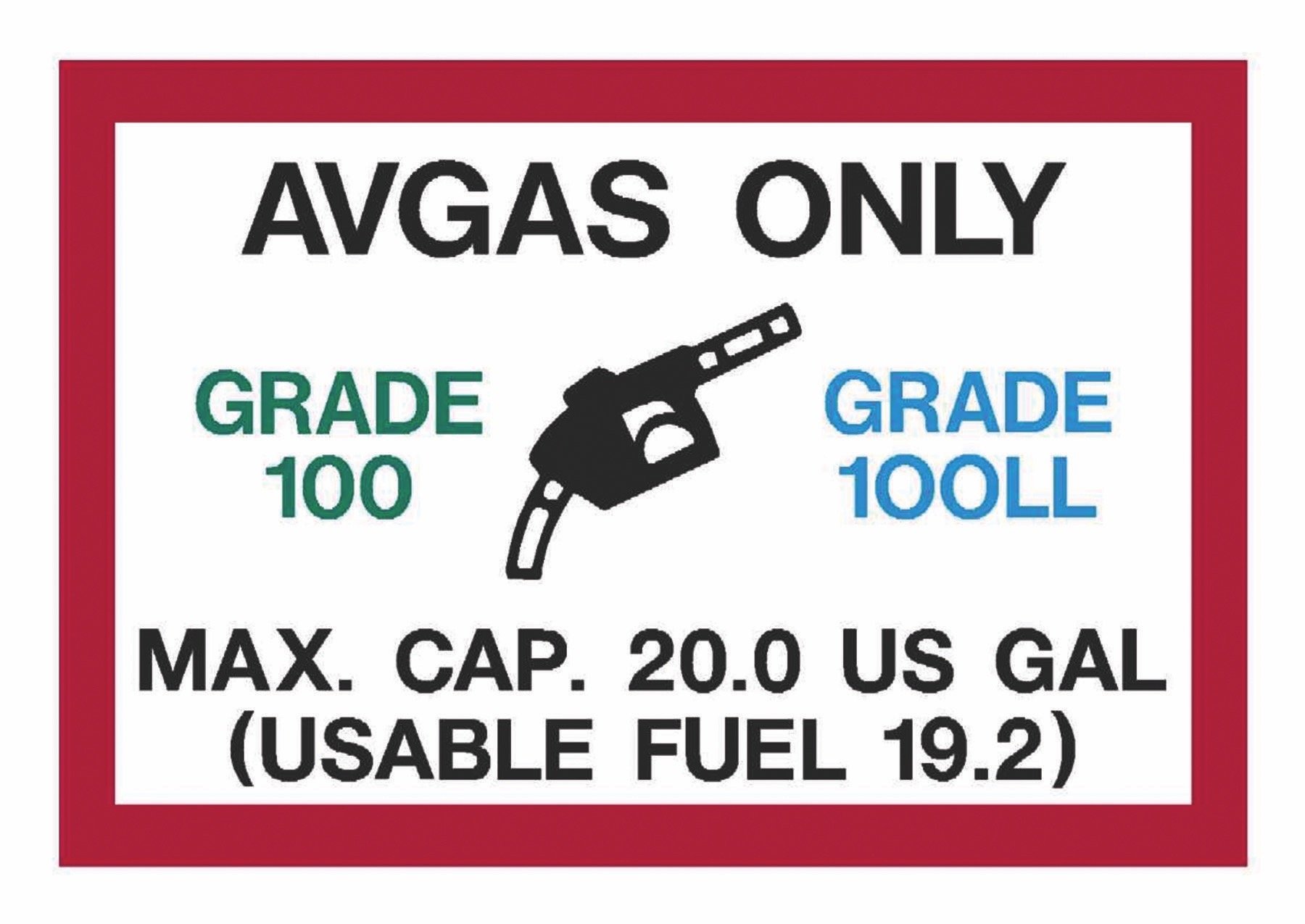

In this month’s Quick Turns department, beginning on page 22, we spend some time dissecting recent developments associated with the PAFI (Piston Aviation Fuels Initiative) program. As we note, it’s not at all clear whether the program has any life left in it and, if so, who’s going to participate. Also unclear is why things are in the state they appear. We have questions.

One answer I’d like to hear involves details on what apparent problems PAFI’s Phase II testing of engines and aircraft fuel systems may have uncovered. The lab testing of Phase I was concluded a couple of years ago and the overall program is running at least a year late. We readily understand how delays and slippages occur, but this isn’t rocket science, after all: it’s gasoline, one of the most abundant commodities on the planet. Sure—it’s complicated and stuff, but that’s why PAFI was created, to establish a level playing field and—perhaps above all else—ease the industry into new, uncharted territory armed with the facts, figures and test results creating a consensus demands. That that apparently didn’t happen deserves an explanation we hope will be forthcoming.

Another answer I’d like to hear is how an STC-based approval process for unleaded fuel would work. The actual STC part I readily understand but not the distribution and delivery logistics, especially if more than one unleaded fuel hits the market. And how would an STC’d fuel or two affect any decision to cease manufacturing 100LL? What kinds of assurances will there be that Uncle Jeb’s Backyard Avgas will be available when and where I want/need it, or even if the company holding the approvals for it will be in business next year? And generally, no matter the approval process, what happens if the new unleaded avgas is determined down the road to have long-term incompatibilities with certain airframes or fuel systems? Who’s going to pay to replace my fuel pumps and wing bladders with new, compatible components? I know the answer already, but the question merits attention.

There’s no question an unleaded avgas is something whose time has come. General aviation needs to get past this hurdle and accept the potential harm posed by one of the last leaded fuels available. Meeting the needs of all operators and aircraft comprising the in-service fleet is a huge component of this challenge, if for no other reason than economics: Some 30 percent of the aircraft, which typically are powered by engines with characteristics most likely to need high octane fuel burn approximately 70 percent of the 100LL.

Count us among those hoping this situation works itself out sooner rather than later.