By any measure, the Experimental Aircraft Association’s just-concluded AirVenture fly-in was a success. According to online sister publication AVweb.com, official attendance was “approximately” 677,000—a new record handily blowing past last year’s count of 650,000. According to EAA CEO and President Jack Pelton, “We had record-setting totals of campers, exhibitors, volunteers, and more. It was also a challenging year at times with weather, logistics, and other factors, which makes me even more proud of the efforts by our volunteers and staff to organize an outstanding event.”

Also according to AVweb, more than 10,000 aircraft flew into KOSH and other nearby airports for the show. The FAA logged 21,883 aircraft operations at Wittman Field in the 11-day period from July 20 to July 30. That’s an average of some 148 takeoffs/landings per hour when the airport is open, according to EAA. Other stats include 3365 show planes on display, including 1497 in the vintage aircraft parking area (a new record), 1067 homebuilts and 380 warbirds.

This year’s AirVenture was my first since 2019, thanks to the pandemic and other factors. I can verify the huge crowds, the nonstop activity schedules and sheer immensity of the thing. If AirVenture didn’t exist, we’d all be worse off.

Was there a revolutionary new app, or a 300-knot, four-seat single using tap water for fuel? Nope. In fact, except for some niche markets, there were few clean-sheet airframe designs; those that did appear are kits and won’t be flying for a while. But there were lots of evolutionary announcements, like adding autothrottle and autoland capability to in-service King Airs, for example. There also were new gadgets, of course, and the usual smattering of “how did they do that?” variations in design and modifications, especially in the homebuilt aircraft arena. New avionics offerings were slim as well.

Fisking

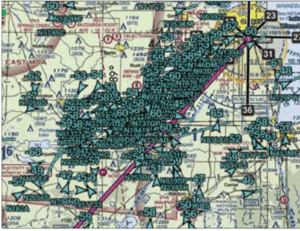

I usually arrive at the show a few days early, in part to watch the show site emerge from seemingly nowhere, like a Brigadoon in the so-called heartland, and in part to watch the arrivals, which are always a hoot. This year, however, commitments conspired to delay my arrival until the day before the show opened. I flew the Fisk arrival with many of those 10,000 aircraft, some of which were up close and personal. Despite my penchant for arriving early, I’ve flown the Fisk arrival before and knew what to expect. I wasn’t disappointed.

If you will permit me the small rant, this year’s Fisk arrival was the worst I’ve experienced. One problem is the sheer length of the conga line of airplanes trying to get to the airport, which in my case extended from Endeavor, Wisconsin, 43 nm from KOSH.

The FAA apparently wants to put arrivals in-trail with each other as far out as possible, presumably to give them plenty of time to establish spacing and settle down, hopefully leading to stabilized approaches at the airport. This is the “put them together to keep them apart” strategy. It wasn’t working the morning I arrived.

Some pilots don’t seem to understand what the “90 knots and 1800 feet” parameters for light airplanes mean in the real world. By the time I was about 10 miles out, I was behind a Cherokee that had slowed to 80 knots or so. I was eating it up, so I had to fly at about 75 knots to try putting some space between us. It wasn’t working, and I got into an uncommanded, wake-induced roll once, then twice. Enough.

I peeled out of the line and motored back the way I came, getting to do it all over again. The second attempt worked a lot better, but not without its own drama. It’s well-understood that flying a procedure like the Fisk arrival is done mostly by pilots who aren’t as proficient as they were on checkride day, but the lengthy arrival procedure is prolonging the opportunities for both mayhem and agony. Requiring arrivals to get in line, and maintain an airspeed and altitude over such a distance, is doing more harm than good. No, I don’t know what the solution is.

Now Under New Ownership

There’s a new logo on our masthead. This magazine and other aviation titles previously published by the Belvoir Media Group are now part of the FLYING Media Group, the parent company of FLYING magazine. It’s clear that CEO Craig Fuller has big plans for this magazine and his other new outlets. I look forward to what comes next. You should, too. Θ

— Jeb Burnside