Instrument flying is a challenging combination of rigid rules and a flexible operating environment. When changes occur, threats present themselves. Staying ahead of the aircraft and managing the flightpath is critical to ensure a safe outcome and avoid potential deviations.

I try to find inspiration for safety topics in my day-to-day flying. While I try to squeeze as much general aviation flying in as I can, airline flying vastly outweighs my logbook entries as of late. So, when I find myself in a situation where I could imagine any pilot being tripped up, I attempt to turn on the ole mental tape recorder and see where the threats lie, and what went right and what went wrong while we worked through it. Such an event occurred to me recently. The names and locations have been changed to protect the innocent.

Hurry Up And Wait

During the aforementioned flight, we were eyeballing the weather at the destination before we even departed. It was a race against thunderstorms and the traffic jams they created. Before we even began the descent, there were four route changes. It got to the point where we stopped briefing the changes because as soon as the changes were plugged in and we talked about it, like clockwork, another reroute popped up.

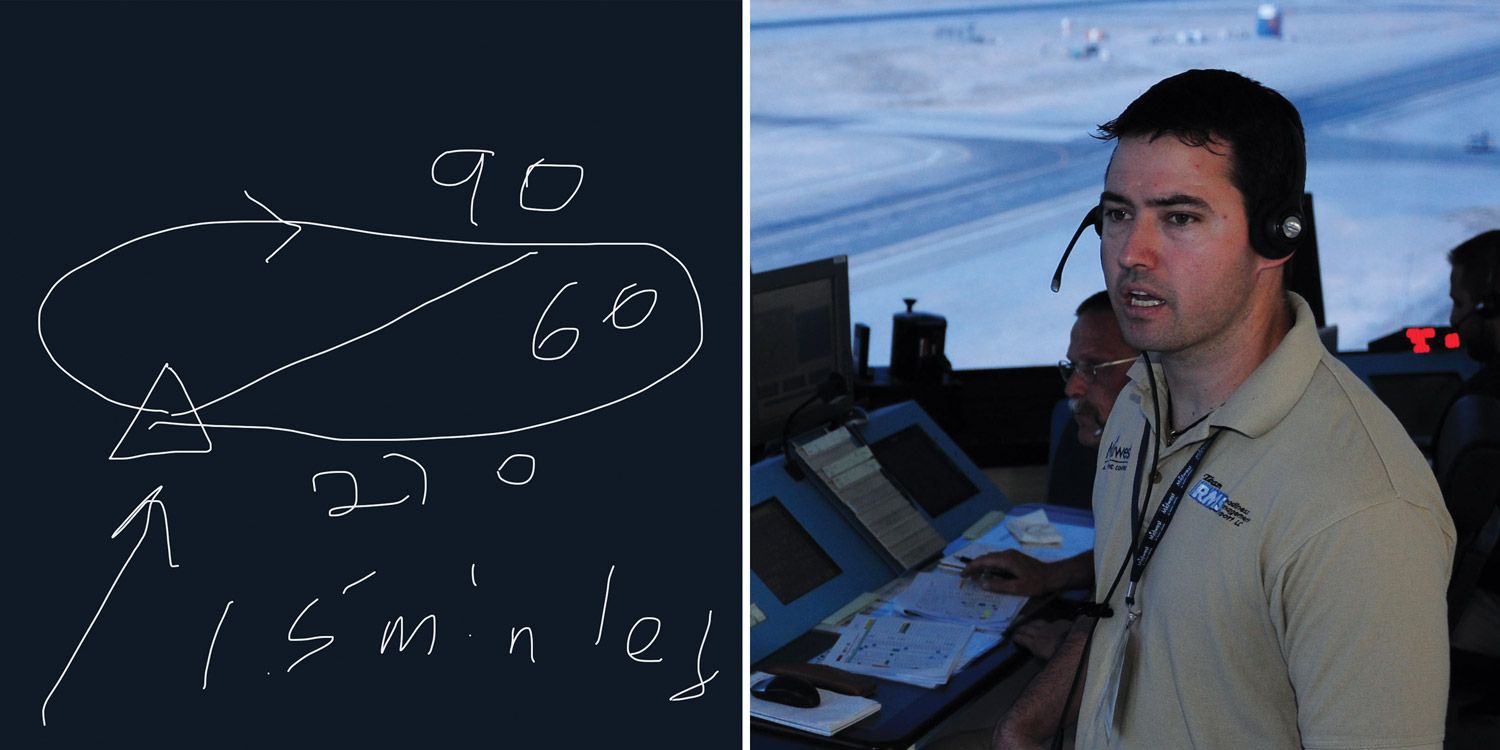

Mother Nature won the race that day, and we were sent north of the airport to hold and wait out the weather. The thunderstorms were moving southwest to northeast, so they issued another reroute in the hold to the southbound arrival. The runway normally associated with that arrival was congested with traffic actually coming from the south, so we were given a different runway. Feeling some relief that a plan was coming together before we faced a diversion, we trucked on. We exited the hold…and were immediately cleared to return to our hold. The winds shifted and they needed to turn the airport around. Windshear (probably the reason for the shifting winds in the first place) was reported on the field, so the airport closed briefly.

It sounds like hyperbole, but before we eventually worked our way toward the airport, we had set up at least 15 different approaches and arrivals. Yes, there were repeats. Get approach 2 set up and then forget it; back to approach 1, expect vectors. You get the idea. The proverbial icing on the cake was when ATC finally turned us in, the clearance involved rocketing toward the airport at 300 knots. So, with our heads full of approaches, arrivals, minimums, runways, taxiways…we were asked to go as fast as we could possibly go. Talk about adding links to the chain.

Instead, we told ATC “unable” and settled on a slower speed. After we safely completed the flight, we debriefed what went well and what could be improved for next time. Here are some of the tools that helped me manage the flight with more changes than I have ever experienced.

In this article, I urge avoiding distractions, but that’s just about impossible when actually navigating a new clearance or a diversion. It’s tantamount to remember that priority one is flying the aircraft and that the distraction itself is the biggest threat. Beyond that, here are some additional tips.

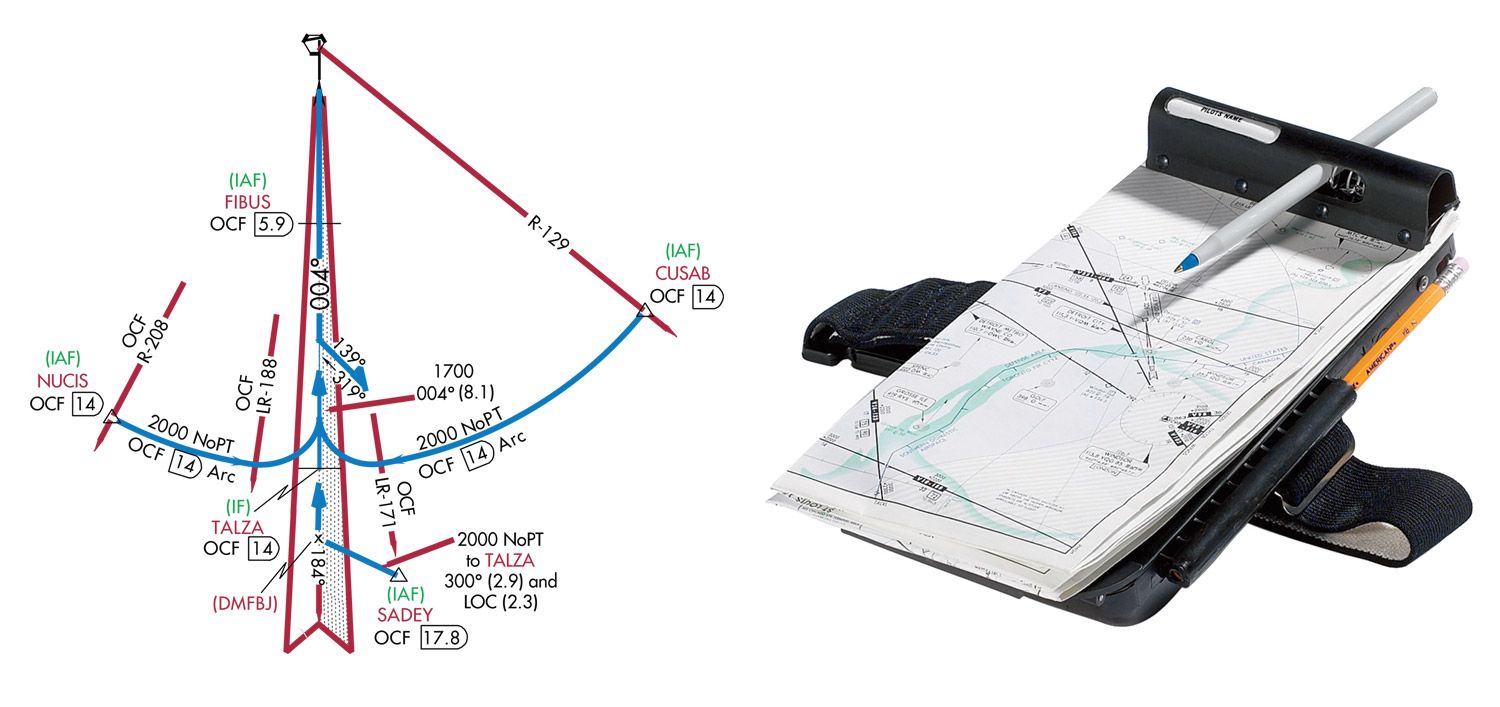

Write it Down

I am always impressed when at a restaurant and the server takes eight orders and does not write a single thing down, but it’s not a technique I recommend when dealing with ATC. Additionally, this is a great way to remind yourself to complete a task or check something down the road. I have been halfway through a checklist or studying Notams when interrupted by something more pressing. Leaving myself a quick note is my trick to remind myself to come back to whatever I was doing before.

Slow it Down

While I think it is inadvisable to fly around in slow flight, there is no reason to go screaming around at max cruise in a holding pattern or on a vector in the wrong direction. While ATC pushes traffic as efficiently as they can, it’s on us to advise them if we need to slow things down or change the plan.

Set Gates

A gate in this case is a line in the sand where certain criteria need to be met in order to continue toward the next phase of flight. Most commonly for this, we reference the stabilized approach criteria, but when dealing with non-standard situations, it’s better to move the line up. For example, I will not proceed past the final approach fix if the aircraft is not configured to land and all checklists are completed. Not only does this stop a chain of events before it begins, but it also turns a high-workload go-around into simpler delay vectors. Other examples for gates would be top of descent, or 10 minutes from landing. Setting reminders throughout the flight can help alleviate distraction and pull us back into the most important tasks.

Back To Basics

The most prevalent initial threat when a substantial change pops up is distraction. Speaking from experience, this can be challenging even in a crewed aircraft with a functioning autopilot. I often reflect on airline-style flying where it would be a cardinal sin to be “heads down,” meaning not actively monitoring the aircraft’s flying path while completing tasks like setting up or briefing an approach. This compared to my instrument training where during a long cross-country. I was fresh off a missed approach, in the hold trying to verify my route home on the en route chart because it was different than the one I filed.

The reason why I titled this section “Back To Basics” is because the best way to mitigate the most severe of the threats posed by in-flight changes is to aviate, navigate, communicate. In my example of task saturation above, my biggest distractor was route verification. ATC’s new route was quite a bit longer than my planned route, and I was concerned about fuel. This is concerning, but doing that level of flight planning while hand-flying an intersection hold in IMC means neither are being given the attention they deserve.

Once you start to notice deviations from your flight path, it is time for that to become the focus. Loss of control, CFIT and loss of separation are catastrophic events that can rapidly develop when deviating from the intended flight path. If need be, simplify the aviating. Request a vector and altitude assignment, or whatever will reduce your workload. Substantial changes are usually the result of substantial weather or other disruptions, so ATC workload does factor into this.

Considerations

I tried to come up with an acronym for this, and it is probably for the best that I failed because aviation is already too full of acronyms and I am pretty sure that every time I learn a new one, I forget an old one. When I am dealt a substantial change to my flight, I consider the following:

Checklists: Checklists get interrupted remarkably often. A good rule of thumb is that an interrupted checklist means you start again from the top and run through everything. When I was a simulator instructor, one of my favorite failures was a minor bleed issue right after takeoff. One of two things would happen about 80 percent of the time. Either the crew would rush through the after-takeoff checklist or forego it entirely. A mostly harmless but fun a-ha! moment followed when they realized the gear was still down from their initial takeoff. Once the dust settles from an in-flight change, take your time and make sure all your checklists are complete.

Configuration and Procedures: Hand-in-hand with checklists, after our normal flow is interrupted with a substantial change in flight, take a long, healthy scan of the flight deck. Are all the switches and knobs where we want them? Things like cowl flaps, leaned mixtures, fuel tanks all selected in the appropriate position? Often, we get reroutes and changes due to a mechanical diversion. After we aviate, navigate and communicate toward a new airport, are there any additional considerations for the mechanical?

Fuel: In many ways, I am happy I learned flight planning the old-fashioned way. It makes me really appreciate the quick and mostly accurate calculations my EFB does in situations like this. I recommend erring on the side of caution and then some. If the change that faces you is a hold, it is prudent to prepare for the worst outcome. Pick a suitable airport (or two), considering weather, services and infrastructure, and conservatively calculate the fuel burn. Then consider the remaining fuel burn to your preferred destination, the alternate airport, and legal reserves. The higher of these two numbers creates a decision point. Once my legal alternate was about 30 minutes past my planned destination and weather was forcing us into a hold. We changed our alternate to an airport right below the hold and extended our holding time by about 30 minutes. Sadly, it still ended in a diversion, but it was a valiant effort and it made for an easy gas and go.

Final Thoughts

Major changes in flight incur distraction and add to our workload. If we slow things down and ensure that we are always monitoring the flight path, we mitigate most of the threats. Unless a mechanical or fuel issue requires immediate action, we can almost always build time in to give our new clearance or destination the deliberation it deserves.

As a safety guy, I know rushing leads to errors, and they are almost always unforced. Yet I still consistently must check myself when asked, “How much longer until you are going to be ready?” or, “How much speed can you give me? You are number one to the field.” Sometimes it can be challenging to notice in yourself, especially if you are proficient in the aircraft. If checklists are getting rushed or critical steps are getting missed, it is time to slow down. One method of slowing things down is telling ATC “unable.”

If you do need to scramble ATC’s plan, it is prudent to give them as much information as possible and any alternatives you have. For example, if you need time to run some checklists before takeoff, let ground or tower know as soon as you can, and do not be afraid to give yourself a buffer. If you are reviewing changes and need more time in flight, asking for a vector or hold can go a long way. The most important thing is that everyone is on the same page. Speak up if there is ever uncertainty. Even the grumpiest controllers would much rather reissue or clarify a clearance than fill out paperwork if there is a loss of separation.

If you do need to scramble ATC’s plan, it is prudent to give them as much information as possible and any alternatives you have. For example, if you need time to run some checklists before takeoff, let ground or tower know as soon as you can, and do not be afraid to give yourself a buffer. If you are reviewing changes and need more time in flight, asking for a vector or hold can go a long way. The most important thing is that everyone is on the same page. Speak up if there is ever uncertainty. Even the grumpiest controllers would much rather reissue or clarify a clearance than fill out paperwork if there is a loss of separation.