The nighttime arrival at a familiar airport had gone smoothly. The runway I used was 5000-plus feet long, way more than my Debonair needed, so I let it roll a bit to save the brakes. I must have gotten distracted during the rollout because the next thing I noticed was the end of the runway coming up, fast. I still had about 30 knots of speed—perhaps I hadn’t fully closed the throttle on landing. I stomped on the brakes, fully retarded the throttle and pulled the yoke back into my gut. We slowed sharply, and I negotiated the turn onto the taxiway to the ramp without further drama.

That’s the last time I remember being even close to running out of runway on landing. I learned a few lessons that night, which have helped keep me out of the weeds since, unlike what happened to a regional jet crew, preserved for posterity in the image below. One of the things I learned is that planning to come to a stop after landing begins well before touching down.

GOT RUNWAY?

In fact, planning to stop really begins with the choice of runway. In the case of the nighttime landing I just related, the runway was the longest available at my destination, and happened to be closely aligned with the wind. And I had planned to let it roll out full-length, anyway, knowing that the quickest route to the transient parking ramp was to hang a left at the end.

At another airport, I may have planned it differently, perhaps to get down, stopped and off the runway as quickly as possible. I may have aimed to clear the runway adjacent to the FBO I planned to use, or use the closest taxiway to my hangar. The point is that planning to come to a stop after landing starts before touchdown, by deciding where on the airport you want to end up, and perhaps how to minimize taxi time once landed. After all, it’s usually easier on the airplane to fly than taxi.

Sometimes, you don’t have much choice. My home-plate runway isn’t the longest of its kind, so I generally plan to use all of it. It drains well, so it’s unlikely there will be standing water, and I can use pretty much all the braking I want without worrying about hydroplaning (see the sidebar at the bottom of the opposite page). But it pays to be on-speed. And that’s the next trick related to getting down and stopped: fly the recommended speeds. Every extra knot exponentially increases the energy your brakes must dissipate to stop, and the distance it takes.

One question that comes up often is how to maximize braking and brake life, by pumping/pulsing the brakes are firmly applying steady pressure. In its discussion of hydroplaning (see the sidebar below), the FAA’s Airplane Flying Handbook has this to say:

Proper braking technique is essential. The brakes are applied firmly until reaching a point just short of a skid. At the first sign of a skid, release brake pressure and allow the wheels to spin up. Directional control is maintained as far as possible with the rudder.

TOUCHING DOWN

One important thing about being on-speed at touchdown is it’s the only real way to obtain “book” landing performance. That couple of extra knots you carried over the fence isn’t just going to magically disappear on your say-so. If there’s a real desire on your part to get down and stopped in as little distance as possible, you need to pick the right speed, generally 1.2 VSO, adjusted for weight, or as your POH/AFM recommends.

This isn’t the time to use all your finesse; get it firmly on the ground, finished with flying, so there’s less chance for the tires to skid or lock up when you stomp on the brakes. Then do absolutely nothing but manage the airplane’s directional control, ensure the throttles are properly set and apply maximum braking. You don’t need to risk any distractions by raising the flaps, and you especially don’t want to risk retracting the landing gear, although doing so has been known to dramatically reduce landing distances.

Unless you’re aiming for exiting the runway onto a bona fide high-speed taxiway, remain as close to the centerline as you can until slowed to taxi speed. Only then consider executing a 90-degree (or more) turn off the runway. Two reasons: Your brakes likely are going to be more effective when trying to stop in a straight, not curved line. You also can create unnecessary side loads on the landing-gear if making a sharp turn without slowing.

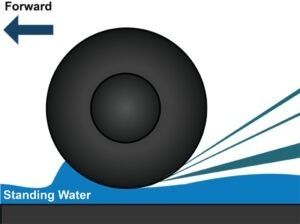

There are three basic types of hydroplaning, a condition in which the tire loses direct contact with the runway:

Dynamic Hydroplaning

According to the FAA’s Airplane Flying Handbook, dynamic hydroplaning is related to tire pressure. The formula is 8.6 times the square root of the tire’s pressure in psi. A 40-psi tire would be susceptible to this kind of hydroplaning at slightly more than 54 knots.

Reverted Rubber Hydroplaning

Reverted rubber hydroplaning occurs when the tire skids, partially liquefies and loses traction.

Viscous Hydroplaning

Viscous hydroplaning relies on a thin film of water over a smooth surface, like a touchdown zone or runway striping.

WEIGHT AND DRAG

At the end of the day, the brakes on a typical personal airplane are pretty basic units, far behind the latest technology in the car you likely drove to the airport. They’re of relatively small diameter, also, when compared to automotive and even motorcycle brake systems. There’re only two tires, not four, and they typically lack any antilock or power-boost features. The point is, they need all the help they can get.

One way to help is with aerodynamic braking: Leave the wing flaps extended, as already discussed, and apply full nose-up input on the pitch control. By pitching the nose up, you’ve increased the amount of drag it generates, helping to slow you down. Even the typical nose-up elevator position creates some additional drag. Same with leaving the flaps deployed.

Pitching the nose up also places the maximum amount of weight on the main wheels, the ones with the brakes. That extra downforce can help prevent skidding the tires when maximum braking is applied. And let there be no mistake: If getting down and stopped as you want requires a maximum effort, you want maximum braking, as much weight on the wheels as possible and as much drag as you can generate.

Yes, there’s an argument that leaving the wing flaps fully extended after touchdown of some high-wing Cessnas (cough, early 172s, cough) and applying full nose-up input on the yoke will increase lift to the point the airplane becomes airborne again. Maybe, but I’d suggest the only way that’s possible is you were light and carried some extra knots into the flare, touching down above stall speed.

That said, dumping lift with spoilers is a time-honored procedure available to jet transport and sailplane pilots alike. If you absolutely, positively feel the need to retract the flaps after touchdown as a way of minimizing any tendency to rebound into the air or maximizing weight on the wheels, at least restrict using such a procedure to fixed-gear airplanes only.

Of course, a lot of this discussion goes out the window when we talk about soft fields. I’m thinking primarily turf/grass landing areas, but dirt and gravel also count. The bottom line is there’s just not enough friction on these surfaces to use maximum braking.

What to do? Well, for starters, ensure the available runway is adequate to your needs. You get to be the judge on whether you can get down and stopped on wet grass, loose dirt or gravel. Having sat in the right seat as a Cessna slid off the end of a grass runway, I can attest to how easily it happens.

The other thing going on here, though, is that at really soft fields, you may not want to stop until in your parking spot. It can require a lot of power to get moving again. Sometimes it’s best to keep moving, with the nosewheel as light as you can get it and judicious use, if any, of the brakes.

SLOW DECELERATION OR…?

On the other hand, you may not care a whit about the shortest stopping distance or making an early taxiway. You’ve got a mile of runway between you and your hangar and why waste the brakes? Should you let it roll like I did on that night landing described at the top of this article, or go ahead and use up some of the brake pads and get slowed down to taxi speed, turn off the runway and use a taxiway to get to your parking spot? It depends.

Generally, it’s preferable to get slowed down as quickly and safely as possible—it’s harder to maintain control when the airplane is decelerating through 40 knots than when it’s already below 20. Yes, there are exceptions: One of them is when the one-turning, one-burning 777 filled with orphans is landing right behind you as soon as you make the high-speed, but that’s about it.

The bottom line is that putting some effort into slowing down to taxi speed as soon as practicable goes a long way toward helping you maintain control, sometimes in poor conditions, and also minimizes any wear and tear to tires and wheels. You can exit the runway sooner, and brake pads are cheap.

Jeb Burnside is this magazine’s editor-in-chief. He’s an airline transport pilot who owns a Beechcraft Debonair, plus the expensive half of an Aeronca 7CCM Champ.

Funny!

“You don’t need to risk any distractions by raising the flaps, and you especially don’t want to risk retracting the landing gear, although doing so has been known to dramatically reduce landing distances.”

It depends… as things usually do. If I have an unextinguished engine fire, wing fire, or (God Help Me!!) cockpit fire the least time to a full stop is REALLY attractive. Wheels UP it is!!!