I have been around the airport water cooler for two different gear-up landings. The first was either a classic excuse or truly unfortunate set of circumstances. After touching the belly of the aircraft to the pavement without a nice, cushy set of wheels between the two, he hopped out of the airplane and declared that the reason he landed gear-up was due to a bee in the cockpit. I never asked if he was allergic to bees, but either way, if his story is true, that little insect caused a lot of damage.

The second story involved a pilot who evacuated his aircraft believing he selected the gear down and it must have collapsed when he landed. After the dust settled, he looked inside the cockpit and found the smoking gun; the gear handle settled in the up position.

If you spend any time chatting in hangars or around the proverbial airport water cooler, you have probably heard similar stories, either first- or second-hand. Or the classic, “There are pilots who have landed gear-up, and those who will.” While this is (hopefully) an exaggeration, very few pilots forgot to put the gear selector down and think, “Well, I knew this would happen eventually.” There is usually some version of the five stages of grief.

WHY DO GEAR-UPS OCCUR?

When accidents or incidents occur, it is important to complete a root-cause analysis. There are many ways to accomplish this. In fact, you can take an upper-level college course on different methods of determining the root case of events. It extends well beyond aviation; basically any field where human error can occur and create catastrophic results will utilize these techniques.

Luckily, many of the methods are extremely simple. Take the “Five Why’s” method, where you ask the question “Why?” until you reach one (or several) root causes for the incident. Here is a scenario loosely based on a true story.

Incident: A pilot lands gear-up after being dropped onto an approach late.

Why did the pilot land gear-up? The pilot forgot to select the gear handle to down.

Why did the pilot forget to select the gear handle down? They were given a late approach clearance that left them high on the approach.

Why did this cause the pilot to land gear-up? No checklists or flows were completed

Why did the pilot skip the checklist? The pilot normally puts the gear down abeam the numbers on downwind, or when the glideslope is a dot high. Neither of those triggers occurred during this flight. Rushing caused the pilot to skip the checklist.

Why did the pilot feel rushed? The change from normal procedure caused the pilot to be task saturated.

You can explore several different avenues for this simple scenario, but I would argue the root cause for this incident would be task saturation and non-standard approach procedures. There is also a case that could be made for continuation bias, where the pilot’s intention was to complete the approach and land, so they continued even in the face of the numerous challenges (late approach clearance, potentially high and fast, misconfigured.) Typically, I consider two main factors in gear-up landings: forgetting and mechanical failure.

Insurance companies endearingly call gear-up landings, “The 60,000 Slide.” Fancy airplanes (like twins!), and the ever-increasing cost of labor and parts, continually drive up that cost. In a prototypical gear-up landing, there is usually substantial damage to the propeller, the engine and the belly of the aircraft. The silver lining is the insurance will cover this, but some work can be done by the insured to maximize value. After all, might as well get the best bang for your buck from those premiums.

Develop a relationship with whatever shop is doing the work and stay involved in the process. Insurance companies will cover your loss, but they will not leave you better off than you were before the claim. An example is the engine teardown after a prop strike. If you are halfway to overhaul anyway, it is worth thinking about just getting it out of the way. The insurance company will pay for the required teardown/inspection, and since you are already halfway there, it is worth considering covering the remainder of the cost out of your own pocket.

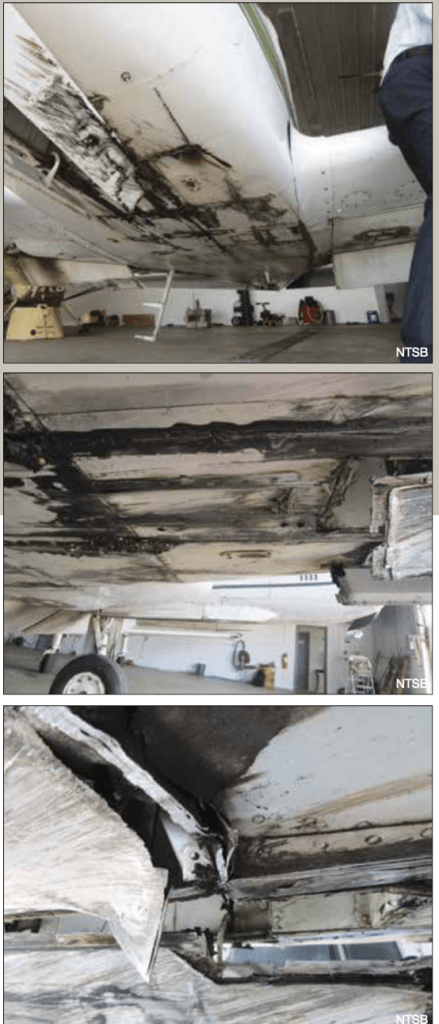

The images at right show the damage that occurred when, according to the NTSB, the pilot failed “to confirm the landing gear was down before landing due to distraction during the Before Landing checks, which resulted in a gear-up landing.”

FORGETTING

I consider the above scenario to be an example of forgetting to put the gear down. The gear works completely fine, but for any number of contributing factors, the handle was never selected down. Like other accidents and incidents, it is rare just one link in the chain will cause a pilot to forget the gear. While this list is not inclusive, below are some common examples of contributing factors that have caused gear-up landings.

Change in procedure: Most pilots have their own standard operating procedures (SOPs). A common example I have seen is putting the gear down abeam the numbers on downwind. This is an excellent habit, building a memory trigger that reminds the pilot that something needs to be done. The downside to this is in non-standard situations, such as a late approach clearance or a pattern adjustment due to traffic. This can shake up the normal routine and remove the trigger, since you may never be abeam the numbers on downwind.

Task Saturation: Any number of things can cause task saturation. We have all felt it. The airport snuck up on you, a separate mechanical issue was present or ATC wants you on a runway different from the one you planned—each can cause task saturation. When this happens, the pilot gets behind the aircraft and deviations are likely.

Distractions: This frequently goes hand-in-hand with task saturation. The story I related earlier about the bee in the cockpit is an example of distractions causing a gear-up landing. A cockpit can be rife with distractions. Beautiful views, passengers, mechanicals and even insects can throw a pilot right out of rhythm.

Fatigue: Fatigue is an extremely challenging factor. When one is tired, performance degradation matches that of intoxication. The kicker is that humans are notoriously poor assessors of their own fatigue. Combine fatigue with the above factors and you have a stew going for poor choices and a high rate of mistakes.

As this article’s main text suggests, one of the best ways to prevent gear-up landings is to develop and adopt standard procedures designed to trigger verification of landing gear extension at certain points in the flight, like abeam the numbers on downwind. Of course, we may not fly abeam the numbers on downwind during our next flight, so some additional SOPs might be in order, like performing a GUMP check at 500 feet agl on final.

Photo Credit: NTSB

If you put “gear-up landing from cockpit” into your favorite search engine, you will find several videos of pilots landing gear-up with the gear-warning alarm blaring. It seems baffling from behind your computer screen, but alarm fatigue is very real. Alarm fatigue can be defined as sensory overload when someone is exposed to an excessive number of alarms, which can result in desensitization to them. The ultimate outcome is missing the alarm altogether. When a human is task-saturated, auditory senses fall by the wayside. Have you ever been so focused on something that you missed someone calling your name? Same thing. Beyond this, most airplanes produce a litany of sounds and alarms. How often are we landing with the stall horn chirping here and there?

There are a few things we can do to prevent this. The best bet is improved alarms. Rather than a consistent tone that differs slightly from a stall warning, something that annunciates “GEAR” would be substantially more effective. Additionally, ensure that you do not allow the gear warning to go off in normal operations. When the horn sounds, the gear should be extended or the condition that is causing the alarm should be fixed. If you are used to flying an approach with the horn blaring, it will not serve its purpose when it is needed.

PREVENTING FORGETTING

The list above does not include every strategy and technique available to prevent gear-up landings, and neither does the one that follows. Risk mitigation strategies are like tools. Each one is appropriate for a different scenario, and one can never have too many tools in your toolbox.

SOPs: I preach SOPs almost constantly, and I am not going to stop now. You probably perform some or all of these procedures already, but if not, they are worth considering. First and most classic is the GUMPS check.

G- Gear Down

U- Undercarriage: Check

M- Make sure the gear is down

P- Please double-check the gear

S- Select the gear handle to down

All kidding aside, the GUMPS check is a fantastic way to introduce flows to your flying. That being said, it is clearly not enough because GUMPS has been taught for a long time and gear-up landings still happen. Fortunately, the airplanes I fly remind me to double check the gear by annunciating, “Five hundred,” every time I descend through 500 feet agl. If your aircraft does not do this, consider adding it yourself. If you call out, “Five hundred, three green down and locked,” each and every landing, you give yourself the opportunity to catch the mistake and go around.

Consistency is key. If you select your gear down at the same time each flight, it becomes harder to miss. However, I list changes in procedure as a contributing factor in gear-up landings. The thing about SOPs is that they are great for standard situations. In all the SOPs I have utilized, there is a caveat near the beginning that says something to the effect of, “All situations are not standard. Deviations from these SOPs are acceptable as long as they are briefed and accepted by all crew.”

The first step is recognition. If you are given a short approach or dropped in too close to the FAF, audibly call it out. Set minimums for yourself. My common technique for visual approaches is to ensure I am configured with checklists complete by 1000 feet agl, complete with a, “One thousand feet, stable and continuing,” call. For instrument approaches, the cutoff point is the Final Approach Fix (FAF). Using a hard number as a cutoff point can stop continuation bias in its tracks and alert the pilot that they are behind the airplane, and that trying again is the safest bet.

My last tip is easier said than done. Keep as current and proficient as possible. When I conduct flight reviews, the most difficult events occur when someone is flying once or twice every few months. Flying is not like riding a bicycle, where you can just hop in after time off and continue right where you left off. Skills atrophy, and it may not be obvious until the links in the chain start forming. It can be like quicksand—by the time you notice the problem, it might be too late to fix it. If you feel like you may be lacking proficiency, a quick way to regain it is to fly with an instructor or an experienced pilot. Hanging out by the airport watercooler is another great way to meet people interested in helping out. After all, who doesn’t want to go flying?

Every airplane equipped with retractable landing gear has some backup method for extending it when the normal procedures don’t work. It could be a hand crank (Bonanza), free-fall (Piper Arrow), hydraulic hand pump like the one at right (Cessna high-wing retracts) or some other method. Regardless, one key is to use the appropriate checklist to run through the emergency extension procedures.

Another key is to fly the airplane. You might want to find a quiet area away from the destination airport to run the checklist, and you might want to slow down, so that neither the mechanism nor your arm has to work so hard. A final key is to have practiced the procedure with an instructor or safety pilot. — J.B.

MECHANICAL

I am going to spend a bit less time talking about mechanical gear failures, because they are a lot less preventable. One hundred percent of the incidents where a pilot forgot to put the gear down were preventable. There is no data on mechanical failures that were preventable, because it is almost impossible to quantify.

When talking about mechanical gear failures, there are mostly two results: the failure of the gear to extend and/or lock, and gear that is down and locked collapsing after landing. Having the gear not locked in the down position is scary, but extremely survivable. Outside of avoiding hard landings, if your gear happens to collapse during landing, there really is not anything you can do except enjoy the ride and remember your evacuation procedures.

Ultimately, with mechanical issues, prevention is the best cure. Be diligent on preflight and ensure all inspections are up to date. If something looks off, consult a mechanic. Meanwhile, consider the tips in the sidebar above for emergency extensions.

THREE DOWN AND LOCKED

The lion’s share of gear-up landings are preventable. Fly each flight the same way, and do not get complacent with checklists and procedures. If something is out of the ordinary, recognize it and adjust your plan to meet the new situation. Following hard minimums for stabilized approaches, even VFR, can save the paint on the bottom of your plane. With any luck, we can avoid becoming that pilot who will land gear-up.

Ryan Motte is a Massachusetts-based Part 135 pilot, flight instructor and check airman. He moonlights as Director of Safety when he isn’t flying.

I was warming my Rotax engine up to the required temperature in my Kitfox before I could takeoff, so sitting there I was watching a twin aircraft coming in, getting lower and lower, thought maybe they were just making a low pass, almost didn’t say anything, not sure why I did it, but I hit the transmit button and casually said “No Gear?” not expecting anything… But wow, I saw a sudden jerk up movement, then full power, still sinking….then finally start to lift up and out……it was close!! Never heard a word and the plane did not come back.. But it was obvious I saved that pilot from embarrassment and damage to his aircraft. Glad I said something!!

I flight instructed for many years and the one airplane that concerned me most was the Cessna 172RG Cutlass — and not because the engineers had done anything wrong with designing or, or that the gear system was other than adequate. My problem was that I had flown something around 2500 hours in the original, 145/150/160 hp Cessna 172s and the cockpit appearance — its frame as I was flying — carefully reminded me on every single Cutlass approach that I was flying a fixed gear Cessna 172. GUMP checks didn’t improve my confidence. Another “stall warning” blare in the flare wouldn’t have helped. It was a struggle for me to get through every approach in that airplane.

It wasn’t that I lacked retractable gear experience. 50 years ago I had flown as a 135 pilot in Barons and on every approach, I was hyper tuned to never forgetting that gear. Later I was a B747 and B777 Captain and the same thing, hyper aware of gear position on every approach (not that had any worries because all the guys I flew with were equally cognizant of gear position had I somehow overlooked it).

Then at the little airport where I live, I attended (that is, appeared shortly after the fact) two separate gear up landings in two separate Cessna 172 RG Cutlasses, both flown by high time flight instructors with students getting their “complex” endorsement instruction. Both airplanes were reported salvageable yet both were ultimately parted out. I was kind of happy when those airplanes were gone. My concern extended only to the RG version; my wife and I have owned 3 of the original fixed gear Skyhawk versions and have nothing but praise for the type as a trainer and family hack.

Maybe in edition 2, you could include a section on “susceptible gear up candidate aircraft types?”

Good information. I’ve had two GUs in a cardinal. Both were hydraulic failures – blown nose gear hose, and last was a pin-hole leak that, under pressure, misdirected nessary pressure to the system. Since then, I’ve added a pump running lite that announces pump action. I’ve replaced all hoses with the highest quality available, and placed hydraulic line examination during annuals as a main priority. If I notice my pump lite flicker during flight, ( indicating a drow in pressure), I would lower gear asap and leave them down.