Like many pilots, I vividly remember being handed my temporary private pilot certificate with my examiner’s congratulations and his admonishment that it was a “license to learn.” Through the years after, I heard then taught and later often wrote about how the FAA practical test standards (PTS), now the airmen certification standards (ACS), represent a minimum standard of performance and safety, even as I worked my way up to an airline transport pilot (ATP) certificate.

I took a quote from the old PTS booklet, which included a note to examiners that all checkride tasks must be performed so the applicant demonstrates mastery of the aircraft, with the successful outcome of each task never in doubt, as inspiration for my personal Mastery Flight Training, Inc. business name.

But no FAA guidance defines what mastery means in this context, and no lesson plans exist (to my knowledge) that describe how to teach and assess a pilot’s level of mastery of the aircraft, the environment and the pilot him/herself. As I gained experience both in the command seat as well as the instructor’s, I began to collect examples of precision and expertise in my own flying. So what are these little moments of mastery that quantify my current, ever-changing execution of flying skills? How might I determine whether I’m attaining aviation mastery?

Put each individual skill together and you’ll see the minimum standard consists of up to six tolerances:

• An acceptable range of altitude while flying the maneuver;

• An acceptable range of heading to fly or to be flying within when completing the maneuver;

• An acceptable range of airspeed before, during or after a maneuver;

• An acceptable bank angle during a skill;

• An acceptable vertical glide path during a descent; and/or

• An acceptable position to be in during or after a task, such as the touchdown spot during a normal or short field landing.

Each maneuver combines one or more of these tolerances to measure the minimum standard of performance and safety. In general (but not always), advanced certificates have tighter tolerances, but the performance being measured remains the same.

THE PTS/ACS BIG PICTURE

Many Aviation Safety readers are far enough along with their pilot certification and rating goals that they will probably never take an FAA checkride again. A private pilot certificate with an instrument rating is enough to operate something as complex as a TBM 960 or a Pilatus PC-12 for personal use, or in support of their profession or business, and I know pilots doing just that on those credentials alone. So for many of us, the PTS is a dim memory and the ACS a set of books we may never crack open.

But if you think back to the last checkride you took, or pop open an ACS and read through the latest standards, you might detect some global themes in completion standards. Each maneuver’s standards describe tolerances—minimum standards—within which we must fly to pass. What is the big picture of the standards we’re required to meet? I summarized them for the sidebar below.

In addition to measuring tolerances, the PTS/ACS evaluate the quality of flight during each maneuver. Specifically, most operations must be flown in coordinated flight, with good use of rudder control. Some specialty tasks, like slips to a landing and single-engine maneuvering in multiengine aircraft, have different but still-defined rudder use criteria.

If the published standard represents a minimum, then mastery comes from flying each maneuver to tighter tolerances while maintaining the desired quality. To gauge your current level of mastery for a given task, compare your actual performance to the standards and see just how much you exceed that minimum, and then maintain that quality.

The very best tool cockpit precision and awareness is one that a great many pilots rarely use in-flight: checklists. I suspect the reason many pilots don’t use them in all phases of flight is because most instructors don’t teach how to use them properly.

Checklists are a great tool for teaching complex skills. They are presented in the proper order, either because that order is desirable or because they must be done in that specific sequence. Following a checklist ensures all required actions are complete. What’s worse, because of this training—or lack of it—many pilots and the instructors teaching them abandon the checklists once the pilot “learns to fly.” In other words, checklists are considered a crutch for the unskilled and uneducated.

Referencing a checklist after you believe you’ve completed all actions to enter a new phase of flight, such as transitioning from climb to cruise, from cruise to descent or from descent to approach, provides confirmation you actually did accomplish them and catches anything you may have missed. Periodically pausing to read and process a checklist sets the pace for your actions, keeping you on-task in some cases and keeping you appropriately slowed down in others. Checklists help you make a mental shift, projecting from one phase of flight to the next. No wonder checklist use in all phases of flight is mandatory on professional flight decks.

A key to flying mastery is consistent use of checklists. Use them like the pros—to confirm, protect, pace and project. Ask yourself, “Did I back up my actions with a printed or electronic checklist with every change in phase of flight? If not, how can I do better next time?”

AN EXERCISE

For example, most airplanes have a noticeable difference between climb and cruise speeds. That means the trim requirement will change as the airplane transitions from one phase of flight to another; the trim changes makes it more challenging to be extremely precise within the tolerances used to define success. And the change is not instantaneous. Begin the process of leveling off, and the airplane will tend to continue its climb unless you actively resist that tendency. Once level, as the airplane accelerates, it will take progressively more nose-down trim—continuing to climb unless the pilot masterfully makes the change. When power is adjusted for cruise, the trim requirement may change again; even leaning the mixture may change the power output enough to require fine-tuning the pitch trim.

The PTS/ACS do not specifically evaluate the task “level off from climb into cruise.” The private pilot standards do, however, judge altitude tolerance for cruise flight: plus/minus 200 feet. Certain other maneuvers have tighter altitude tolerances on checkrides for more advanced pilot credentials. When I took my ATP checkride in 2000, the PTS included flight at minimum controllable airspeed with a tolerance of plus/minus 50 feet…reported at the time to be the most commonly “busted” ATP checkride item. All these minimum criteria for altitude control give us a goal for mastery in our day-to-day flying. After leveling off, ask yourself: “Did I level off within 50 feet of the desired altitude? Twenty feet? If not, what can I do to better master the level off?

Do this for every transition: climb to cruise, cruise to descent, etc. Measure your performance against the minimum PTS/ACS standard and see just how much better or worse you actually are at this moment in time. Note I’m talking about hand-flying the aircraft: In this exercise you’re evaluating your hands-on mastery of the aircraft.

The day’s mission was to fly two friends an hour and a half up the road, drop them and head home. It was going to be a four-landing day. Soon, we were letting down into the friends’ destination on an IFR clearance. We were almost close enough to eyeball the airport, but not quite.

About that time, ATC came on the frequency with something like, “Be advised of several small towers at your twelve o’clock and less than five miles extending to 1500 feet.” Still about 10 miles out, we were passing through 2500 feet msl on the way to a five-mile straight-in for the destination’s only pavement. I leveled off momentarily until I could visually acquire the towers and ensure that we would clear them. About that time, my avionics started to add some yellow. The rest of the approach and landing were uneventful.

Although I was familiar with the town we were going to, I’d never flown into its airport. During my pre-flight planning, I spent more time studying the available approaches than scanning the local sectional for obstacles. Oops. — J.B.

MASTER THE ENVIRONMENT

Another aspect you should consider mastering is the operating environment, including how efficient you are on the radio. The keys to success in communications are being precise and concise. Say what you need to say as correctly as possible in the fewest possible words. Grade yourself on how crisp and focused you are on the radio.

I’ve flown with some very experienced pilots who fumble the process of departing a tower-controlled airport. In their defense, not every pilot flies from controlled fields all the time, and at times there are local variations on the process. In general, though, a tower-controlled airport will have some or all of these services. When they do, there is a correct order in which to use them, and each human you speak to will expect different information. In order of use for departure:

ATIS or AWOS/ASOS: Write down the weather and Notam information first, as well as ATIS information identifier.

Clearance Delivery (CD): Contact CD for your IFR clearance or, if flying VFR, to depart Class B/C airspace. Clearance delivery typically doesn’t care if you have the ATIS or other weather and may be combined with ground control. Examples of your initial transmission are:

For IFR: “Wichita Clearance, N12345 requests IFR to Nashville.”

For VFR: “Wichita Clearance, N12345 is a C172, request VFR northeast, 3500 feet.”

Read back your entire clearance, precisely and concisely. If you have questions about your clearance, now’s a good time to ask.

Ground Control: Ground, on the other hand, wants to know you “have the weather.” They already know the clearance you got from CD, so your initial call-up is simple: “Ground, N12345 at Signature with information Charlie, taxi.”

Just as with a departure clearance, read back your taxi instructions precisely and concisely, especially those involving runway crossings or holding short. You’ve written all this down, right?

Tower: When you’ve completed all checklist items and are ready to depart, taxi to the hold line and radio: “Tower, N12345 ready to depart 19 Left.” Read back hold-short or line-up-and-wait instructions, or your takeoff clearance initial heading and altitude.

For mastery, also have the departure frequency tuned in the standby or on a second radio so you don’t have to tune it during initial climb but can switch with a single push of a button. Similarly, be precise and concise with all handoffs en route. And for true mastery, look on your destination’s approach chart for the controlling facility frequency prior to handoff to tower or switching to CTAF. Listen to ATIS, AWOS or ASOS before you’re handed off to that controlling facility so that when you’re assigned that frequency, you can check in with, “Approach, N12345 7000 with Hotel” or, “Center, N12345 at 5000 with the John Tune weather.”

After flight, score yourself: Were you precise and concise with all radio communications? What might you have done better?

YOUR PLACE IN SPACE

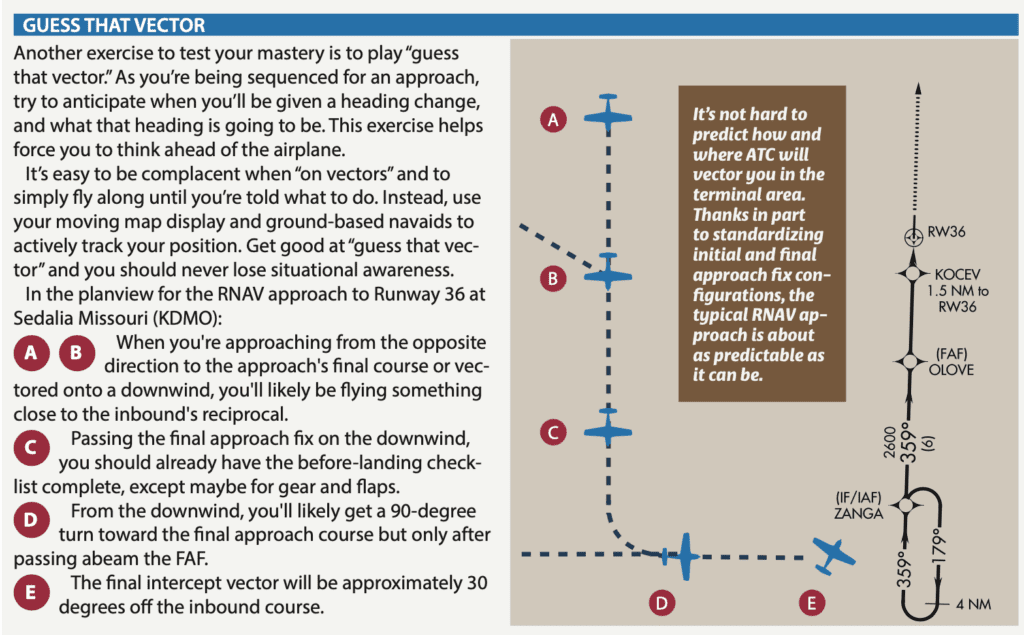

Manipulating the controls is only part of what it takes to master an aircraft. Just as important is spatial orientation—seeing where you are in the total air-traffic picture and where you are going. You can judge your own situational awareness by debriefing yourself after completing a flight.

Listen to ATC, not only for your call sign but also for other aircraft and visualize where they are in relation to you. Who/what are you following on the approach? Who/what is following you? If you hear an airplane checking in after takeoff, envision whether its path or yours will require a restriction. For instance, if you’re at 7000 feet and you hear a departing jet restricted to 6000, chances are it’s coming your way and you’re why it must level off. If controllers provide a traffic advisory to another aircraft at your altitude, think about where it might be in relation to you. Check your guess against traffic observed on an ADS-B display.

When your GPS message icon begins to flash, signifying an advisory, don’t immediately reach over and tap it to reveal the message. First ask yourself what the message will be, and see how often you know what the problem is.

You know another airplane is in your general area when you hear not only controller communications to that aircraft, but also the pilot’s reply. In other words, you’re in the same sector. When you hear another airplane in your sector handed off to the next controller, tune the frequency that airplane had been assigned into the backup on your comm radio—if you’re going the same way, that’s probably the frequency you’ll be assigned as well.

GAMIFY

A pilot’s certificate is indeed a license to learn. How might you determine if you’re improving on your flying and situational awareness skills? “Gamify” your flights: Try to think ahead of what’s right in front of you and visualize what happens next. After your flight, reflect and honestly score your performance. Decide what you did well and what you could have done better. On subsequent flights, work to fill any gaps in your skills. Look for those little moments of mastery every time you fly.

Tom Turner is a CFII-MEI who frequently writes and lectures on aviation safety.