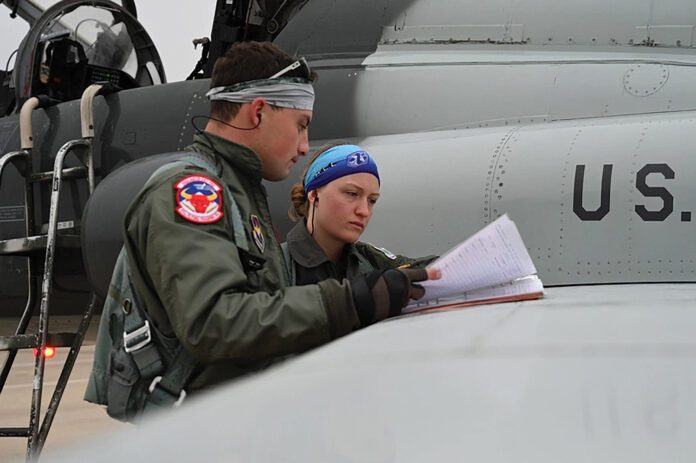

I first became an instructor pilot—an IP—in the U.S. Air Force. This was four years after starting as a warm lump of flesh in a flight suit, a ball of clay to be molded. As a student pilot, I had gone through Undergraduate Pilot Training at Vance Air Force Base, Oklahoma, the “Little Prison Camp on the Prairie.”

Vance’s UPT was tough, and 44 percent of the students that year, across the board in the Air Force at all UPT bases, “washed out.” Didn’t make it, got kicked out of pilot training. The instructors were fierce. I lived in fear of washing out for the entire 50-week program.

So four years later, as a freshly minted USAF IP, I assumed the training environment was the same. Nope. And it took me a while, and more than a few students, to figure it out.

Wake-Up Call

I had just arrived at my new base as an IP, and they scheduled me in the simulator every day while all the other pilots, all younger than me, were out flying the jets. After weeks and weeks of simulators, I ended up verbally hammering some students in the sim, teaching the way I was taught. Right up until I was called on the carpet. Scolded. Counseled. I was told to act “like a big brother” to be “warmer, more encouraging.” Huh?

It’s a “kindler, gentler Air Force now,” I was told. The Air Force had created a massive pilot shortage with their whopping 44 percent washout rate the last few years, and now we had to try to graduate students.

So, to avoid any more wall-to-wall counseling sessions, I mistakenly went from being too harsh to being too nice, kinda like the entire Air Force did, really.

Flying in the pattern with my very first student in a T-38 aircraft flight, the student got low and “drug-in” on final. He got lower and lower, me politely advising him, “I’d pull up and add power if I were you,” and—BAM! We pranged it in the overrun.

Landing in the overrun, it turns out, kicks up a lot of dust and dirt. The “box”—the Runway Supervisory Unit, or RSU, a little air traffic control box next to the runway manned by other IPs—gleefully reported the incident to my flight commander. Pilots sometimes eat their own, I found out.

When I returned to my flight room, my boss, a seasoned 27-year-old veteran of four years on the UPT flight line, said, “Yeah, the box just called me—they said your boy just landed in the overrun.”

I started to explain how the student had the throttles back and got drug in, blah blah blah, and then it was too late to save it, even though I told the student to go to burners. My boss interrupted my rant: “That’s why you’re in the cockpit—you’re the instructor.”

That’s when it hit me. I am an instructor pilot.

The NTSB defines an instruction flight as “Flying while under the supervision of a flight instructor or receiving air carrier training. Personal proficiency flight operations and personal flight reviews, as required by federal air regulations, are excluded.”

The NTSB defines an instruction flight as “Flying while under the supervision of a flight instructor or receiving air carrier training. Personal proficiency flight operations and personal flight reviews, as required by federal air regulations, are excluded.”

From the two graphs presented here, we can see a mostly flat fatal accident rate, accompanied by an uneven non-fatal rate. We also see that landing accidents are rarely fatal while maneuvering remains a risky flight phase. — J.B.

Role Reversal

Before that, I was a student pilot, and then a KC-135Q copilot. “I’m a copilot—no responsibilities and irresponsible!” I heard a C-141 copilot shout one time. (He had been drinking, I deduced, because we were in a bar and he had a glass with liquid in it in his hand. I’m sharp like that.)

I had flown the T-38 for training with other KC-135Q copilots, or with T-38 IPs, and later trained to become an instructor pilot. But I was never actually “responsible,” never a pilot in command. Until now. That overrun landing was a wake-up call. So I reverted to being a bit too careful, too strict. Then a student complained and I got counseled. I struggled to find a happy medium between too nice (dangerous) and too strict (and then getting talked to by upper-ranking officers who flew the scary LGDs—the large grey desks.)

In this “new” training environment, a student who would have washed out four years earlier would “wash back” a class—two classes even—but not wash out like in “the old days.”

I tried being nice (like Mr. Rogers, but without the sweater). For example, I sent a student to a checkride after he made several ugly errors in the flight before the checkride. I had him do the maneuver (single-engine landing) over and over, until it was recognizable, and, to be “nice,” signed him off for his checkride.

The check pilot came into our flight room after the student miserably failed the checkride, and shouted at me, “Captain Johnson, you sent me a brick!” “Brick” meant student, I inferred from context, and “shouting” I deduced, meant anger. That and the flecks of saliva on my face.

I talked too much when flying, and then changed to talking too little when flying. I’d be fairly silent, and then snatch control of the aircraft after I let a situation “go too far,” trying to “be nice.” Then the student would complain that I snatched the controls and startled them without warning them.

Augh! I was too nice and too mean all in 30 seconds.

Fun And Games

I complained about my difficulties to an IP buddy of mine, who had just been awarded “IP of the quarter” (thereby getting a coveted parking spot for three months), and asked him if he had any advice on how to teach.

He said, “I make a game of it. For example, on a pattern if the student doesn’t verbalize ‘handle down, three green, good pressure on two, flaps tracking,’ I tell them, ‘The next time you don’t say it out loud, the next pattern is mine.’”

I realized that’s why he was IP of the quarter—he put effort into teaching creatively. He made a game of it, a sport.

So I tried that, which of course worked. Flying and teaching ground became a sort of game. A serious game, but a “game” just the same. Teaching ground, I’d quiz two or more of them in a “game show” format, me with the big flight manual, two or three students sitting across the desk from me. “Stump the Monkey,” I think we called it. If a student asked me a question, I would ask them a question. Then I remembered we had done this when I was a student pilot, too, but had forgotten it.

I looked back again to my student pilot days. Not all the IPs were harsh. One of the academic instructors had us playing a form of “Jeopardy” in his class, pitting team against team. We loved it. “Sir, I’d like to take Hydraulics for $200” or, “I’ll take Electrics for $500, sir.” Anything that added any kind of competition or sport to our flight training was fun—we students thrived on it.

Transitioning

Years later, as a CFI in the civilian world, I taught in a Grumman AA-5 Traveler and a Cessna 172. First I had to learn to fly the mischievous, ornery machines, both of which fiercely resisted my efforts. I heard them talking with each other on the ramp one time as I approached. Cessna: “‘Psst! Hey! Hey you, Traveler! Shhhh! Here he comes, get ready, heh heh heh. You know what to do—like we briefed.”

After finally making peace with the hostile little beasts, I tried to make a game of learning for the students. I’d say to one student: “Okay, if you can land this one on centerline, at 50 knots or less, no crab, you get $10,000.” Maybe the student wouldn’t quite do it, so I’d take the controls on crosswind and say, “Okay, now you’re 10 grand in the hole—this time, you can double down, go for 20 grand,” etc. Or if the student successfully won the 10 grand, I’d give the option to either keep the 10 grand, or triple down, this time making all radio calls correctly. They loved that game, and really focused. I still owe money to a couple of them.

My mom warned us kids many times, “It’s all fun and games until someone loses an eye.” A fellow T-38 IP had his version of this: “It’s all fun and games until someone loses an eye. Then it’s just fun!” That guy, always smiling, kept his sense of humor in the training environment and made flying fun for his students.

Far From Complacent

But flying can be risky, we know, not all fun and games and chuckles. Just read the accident reports; there are tons of them here and on the interwebs. They’re enough to keep a person up at night, almost.

So, while making flying training fun (interesting, same thing) for students, I have to be constantly vigilant. Why? Because they don’t know every darn thing. That’s why I’m in the cockpit.

I keep my feet near the rudder pedals, my hands in my lap, conveniently near the yoke. I clear like a big dog—out the windows and on the radio. I insist on good checklist usage, conduct thorough preflight briefings every flight, including the positive transfer of aircraft control.

Even though many things in a pre-flight briefing are the same for each flight—like positive transfer of aircraft control—so, too, are the laws of aerodynamics, physics. Oh, and the laws of the FAA; they’re also the same right up until some pilot does something which causes the FAA to go, “Hey!” and make a new law. Strange fact: a pilot can still throw a watermelon out the window. Or a pumpkin. Why? Why not?

A fellow instructor once said, “Watch out for the good students—they’ll kill you.” He meant because a good student flies well and doesn’t make many mistakes, I could be lulled into complacency—and miss the fatal error they do make.

If I, as a CFI, can instill in the learner how serious flying is, we can have a lot of fun flying. Make a game of it. That’s just one of the things I’ve learned flying as a flight instructor. I wasn’t born this way; it took time. Even flight instructors have something to learn.