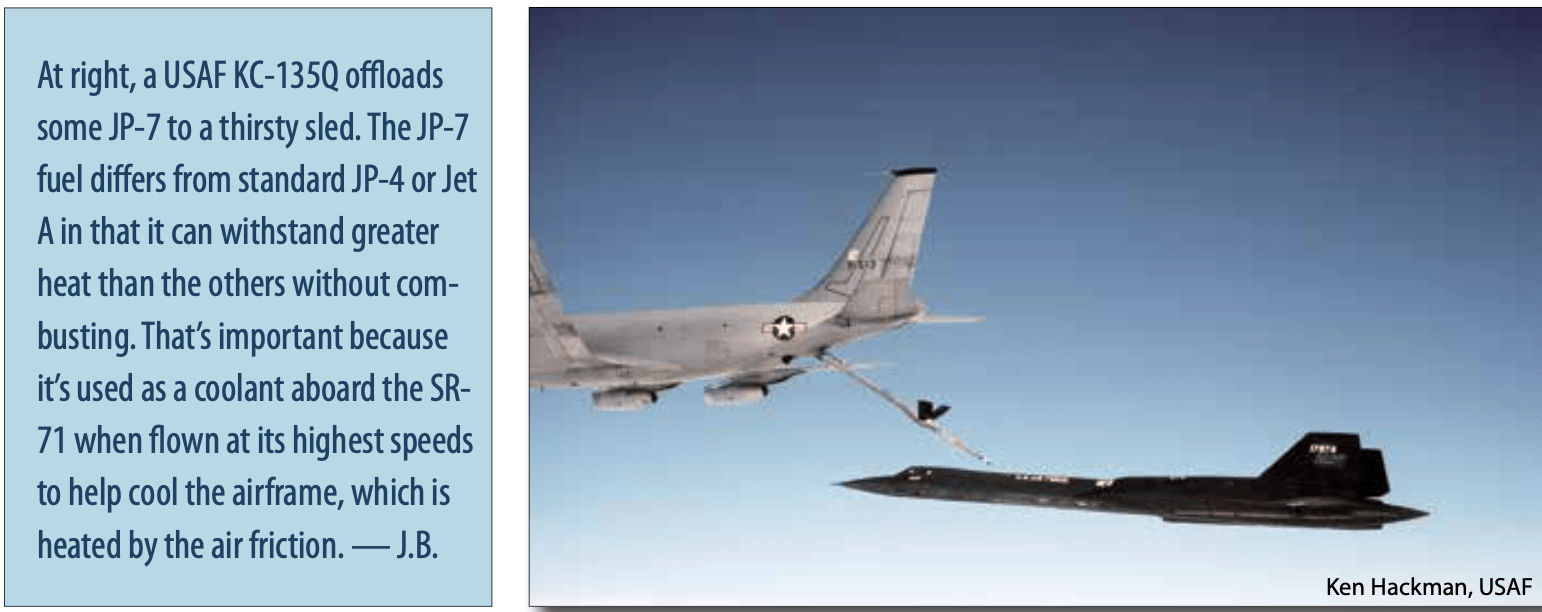

Many years ago, when I was still a bold pilot, I was in the U.S. Air Force, based at Beale AFB and flying as a copilot aboard the KC-135Q, the venerable airborne tanker system based on the Boeing 707. The “Q” version of the KC-135 was specially modified to refuel the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird with JP-7 fuel. Beale was the SR-71’s base, although they—and us—also staged out of other locations.

The SR-71 was large, black, loud and fast. We KC-135Q “tanker” pilots kinda (secretly) worshipped the ground the guys flying it walked on—the “sled” drivers. The guys in the space suits and helmets. (The SR-71 was called the “sled” by all the SR-71 drivers and tanker drivers. Hardly anyone ever called it the “Blackbird” or the “SR-71.” If someone did, you knew right away that person was not a pilot based at Beale AFB.)

We “tanker pukes” refueled the sled on worldwide refueling missions. The sled took pictures of “the bad guys” (North Korea, Russia, China, Vietnam, etc.) using a variety of sensors. Unarmed, the sled’s defense against getting shot down was to fly really fast and really high. How fast and high? Classified. I could tell you. If I knew.

HURRY UP AND WAIT

One day, a pilot named Jack was sitting with me in a KC-135Q “spare” at Mildenhall AFB in England. It was the usual English weather—chilly, with low clouds and drizzle, and people driving on the wrong side of the road. Captain Jack and I (a second lieutenant then) were sitting in the cockpit, ready to take off and refuel the sled if it ran into trouble and needed more fuel to stay airborne to fix a problem.

On an SR-71 mission, the tankers would take off out of Mildenhall, fly for two hours or so way up north off the coast of Norway and orbit in an “anchor” pattern. The sled would take off much later, fly 12 minutes, and meet up with the tankers, get some JP-7, go take pictures, come back, get gas, go shoot more pics, rinse, repeat. After their picture-taking runs, they’d return to base and the tankers would drone on back home, arriving hours later. If the sled ran into trouble between its last refueling and Mildenhall and needed fuel, that’s what the “spare” was for.

It was near the end of the sled’s scheduled mission, and Captain Jack and I had climbed down from the spare to the ramp to stretch our legs. That’s when we heard the radio. The voice on the radio told us to get ready to start engines; the airborne SR-71 had a problem.

Captain Jack was a Vietnam vet and an easygoing guy. Now I saw a no-kidding Captain Jack in action. Once we scrambled up the ladder to the cockpit, he called for the “through flight checklist,” and I started to do the normal “preflight checklist.” His voice got very sharp: “THROUGH FLIGHT CHECK-LIST!” I opened the checklist on my leg to that page—I’d never used it before, in the sim or in real-life. This was real-life now, not a simulator scenario, a real “no-sh*****er,” as pilots called it.

We raced through the abbreviated checklist and were about to start our engines when we overheard the inbound sled on the radio. It was about 10-15 miles out, on an extended final, when we heard the pilot. Then another voice, a sled pilot on the ground using a handheld radio, spoke in a calm voice: “Okay, Dick, you got this—keep her steady, Dicky.”

I had never heard anyone use a person’s name on the radio before, much less a first name, only call signs, and the hair on the back of my neck stood up. In the U.S. Air Force, you just didn’t do that. But these were the sled drivers—if they were using names on the radio, this was serious!

I never forgot that. I thought, when it’s serious, to get a pilot’s attention, to keep him calm in an emergency they use names. Cool.

The sled appeared out of the low-hanging clouds, a black needle-shaped dart of an aircraft, racing toward the runway at close to 200 knots. The pilot landed safely, the orange drag chute billowing out behind it. And that was that.

BACK TO CIVILIAN LIFE

Fast-forward to 2021. I’m a CFI at a small towered airport. The tower itself is new and its controllers do not have radar. The airspace is not even Class Delta. They should call it Class Free airspace, the way the traffic pattern turns into a free-for-all sometimes.

The pattern devolves into a real “goat-rope” (the actual name of the T-38 pattern at Randolph AFB) at times, with as many as nine people in the pattern—aircraft going every which way: left downwind, right downwind, base, final, 45-to-downwind, pilots calling “eight miles out,” “12 miles out,” pilots stepping on each other on the radio, pilots making incorrect calls, or worse—NO calls—and bonus: the tower controller sometimes completely losing control of the pattern. You have your professionals in their Cirruses and Bonanzas, 16-year-old solo students, jets, single-engine turboprops, light twins—it could get sporty out there in a hurry.

A fellow instructor pilot, a CFI, took off one day with two Cub Scouts and I think a den mother, on a short “orientation flight.” She took off right behind me, and I heard her voice on the radio say immediately, “Uh, tower, this is Cessna 12345, we’re gonna come back and land.” I went on high alert, the hair on the back of my neck standing up, just like that cloudy day at Mildenhall, England, with the SR-71 pilots. She had just taken off in an old Cessna with two kids and a mom on board. Maybe a problem—structural damage, engine failure, smoke in the cockpit. She might need help. The tower controller said, “12345, do you require assistance?” The CFI said, “No, we’re okay, no problem,” but I thought that is what she might say even if she did have a problem. It’s pretty much what I would have said in her situation.

I keyed the mic and said, “Julie, this is Al. Are you okay?” I was thinking about that SR-71 pilot using the other pilot’s first name on the radio, to cut through any panic. I could act as a “chase ship” if necessary, flying alongside her, underneath her, telling her what I saw. She said, “No, we’re okay,” and so I continued on my training mission with my student, and forgot about it.

ATC GOES ONLINE

Until I saw the postings on Facebook. One of these tower controllers got quite angry, and ranted about the “incident” on Facebook. I knew who he was—he lost his temper and ranted on the radio a lot, too. That controller was furious that I had keyed the mic and spoken to her! He went on and on about how a pilot had no business talking on the ATC frequency to another pilot, blah blah blah. And blah some more.

And other pilots, being blabber-mouth know-it-alls (ahem, like me) joined the discussion. Many were quick to throw me under the bus, saying oh yes, you are so right, Mr. Tower Master, a pilot had no business talking on the radio. More blah blah blah. At least one pilot went right after that tower controller, asking him if he’d ever flown an airplane, etc. Forced the controller to admit he’d never flown before. Ha! Take that! Then I heard about how I shouldn’t have spoken on the radio—from my boss and my co-workers. (The CFI I offered to help quietly said, “Thank you,” though.) So I vowed to keep silent on the radio unless I needed to speak, in the future. Civilians!

The future came quickly—about a week or so later.

IN THE PATTERN

I was approaching the airfield from the southwest, and saw on my traffic display that there was another aircraft approaching the airport from the southwest, abeam me, about four miles away. We were both angling toward the airport. It looked like that aircraft was slightly faster, probably a Cessna 182, so I turned hard directly toward it, and it spat out ahead of me.

I heard a woman’s voice call out, “Cessna 45678, seven miles southwest of the field, with the weather.” The tower responded “Roger, Cessna 45678, make right traffic for Runway 19.” She responded, and I followed her in trail, maybe four miles behind, with a similar call: “Tower, Cessna 34567, nine miles southwest with the weather.” Tower: “Roger, Cessna 34567, make right traffic for Runway 19.”

Then the confusion began. The goat-rope. The woman pilot ahead of me called out, “Tower, Cessna 45678, 10 miles to the north, with the weather.” Tower: “Roger, Cessna 45678, uhh, call me when you’re five miles out.” I thought, “How the HECK did she get 10 miles out to the north so quickly?” I could only think she went wide open on the throttle and dove, exchanging altitude for airspeed. But 10 miles north of the airport when she was seven miles southwest a few moments ago? Weird.

Then I forgot about her as I did pre-landing checks and cleared the sky, looking out the windscreen, on my iPad and listening on the radio for bogies. This field could be one busy place, and today it was, with about five people in the pattern. Soon, I was almost on the right downwind for Runway 19, and I hear, “Cessna 45678, two miles out.” This was about one minute or so after she had just called 10 miles out. Huh? In a Cessna 182?

Even the tower sounded confused. “How did you get there from ten miles out so quickly?” the controller asked. I’m not quite sure what she did next, but the tower started talking, a lot, instructing me to do a left 360, a pilot on the right downwind to do a 360 and another pilot behind me to do a 360. For spacing. For the 182.

That clueless pilot had flown right into the traffic pattern the wrong way, after missing her 45-to-downwind entry to the pattern. She reported “10 miles north,” then “two miles north,” then re-entered the traffic pattern that she had flown right through. She had done a 180 and re-entered the pattern, scattering the rest of us like bowling pins as she plowed into the airspace. So three of us were doing 360s for spacing, and there were other aircraft in the pattern as well. She finally landed.

I landed, too, and saw a woman getting out of an airplane a few parking spots down. I asked, “Was that you on the radio, calling 10 miles out, then right away calling two miles out?”

She laughed. “Yes, ha ha! I had typed in the wrong fix. Ha ha ha!”

Interacting with someone whose job title includes the word “controller” can be intimidating. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t ask a question or share information. The FAA Advisory Circular AC 90-66B, “Non-Towered Airport Flight Operations,” offers some suggestions that are transferable to towered airports:

Clarify Intentions

Clarify intentions if a communication sent by either their aircraft or another aircraft was potentially not received or misunderstood.

Safety-Essential Communications

Limit communications on CTAF frequencies to safety-essential information regarding arrivals, departures, traffic flow, takeoffs and landings. The CTAF isn’t for personal conversations.

Disagreements

If you disagree with what another pilot is doing, operate your aircraft safely, communicate as necessary, clarify their intentions and, if you feel you must discuss operations with another pilot, wait until you are on the ground. — J.B.

LIVE AND LEARN

I said, “Oh,” and clammed up. I didn’t know what to say to someone who thought what she did was funny. She was basically flying using the instruments, her head down in the cockpit, while we all did acrobatics in the VFR pattern to avoid her.

I was furious with myself for staying silent on the radio while all that happened. I knew she wasn’t 10 miles north of the airport when she made that call—she was just a few miles ahead of me, and I was south of the pattern. There was no way she was 10 miles north, and I knew it.

But I was radio-silent, because I was recently attacked from all sides for speaking to another pilot on the tower frequency just a week or so before, so I said nothing as she blundered through the pattern, made a U-turn, scattered everyone, landed and laughed about it.

I should have called her when she was just ahead of me calling, “10 miles north of the airport,“ and said, “Are you sure you’re 10 miles north of the airport, Cessna 45678?”

Live and learn.

“It’s easier to ask for forgiveness than permission,” I’ve heard. In the future, I’m gonna speak up if I think I need to. “To remain silent when you should speak up makes a coward of a man,” a wise older pilot once told me.

I don’t wanna be a coward again.

Captain Speaking is a former USAF KC-135Q co-pilot. He’s now a CFI at an undisclosed location.