Each season presents its own set of weather challenges. In winter, icing may be more prevalent, along with low ceilings, freezing precipitation and snow-covered runways. Tailwinds can be epic; so can headwinds. Spring and fall can be mirror images, but both often come with good-weather clouds and great visibilities, plus gusty winds and constant change. Summer inverts winter, and brings dissimilar weather extremes along with its own set of challenges, typically including a performance hit courtesy of warmer, less-dense air. But that’s the season in which we find ourselves.

If it’s summer where you are, the good news is you’ve probably had a few weeks to acclimate yourself, your airplane and your expectations to what will be the new norm for at least a couple more months. Most likely, you’re quite happy to trade the snow and ice of winter for the shirtsleeves and warm rains, perhaps less so the thunderstorms. But just as with winter, summer’s extremes can pose operational challenges. They’re just different.

ABOUT PERFORMANCE HITS

Perhaps the most important reality of summer flying is its warmer air, and the reduced performance you can and should expect when compared to the previous winter. Depending on your airplane and where you’re based, that first takeoff in summer heat can be an eye-opener as you roll twice as far down the runway before your flivver feels like flying. What follows might be a struggle to keep the engine and the pilot cool until you can get to cruising altitude, where it might be “only” 70 degrees F.

But how big is that performance hit? There’s an easy and obvious way to find out: run the numbers for your favorite airplane. That’s what I did for my Beech Debonair, using the Bonanza Performance app available free for the download from POH Performance, LLC, from Google Play and the App Store. (The company also offers similar apps for the Cessna 172 and 182, plus the Beech Baron and Daher TBM.) The results are presented in the sidebar on the opposite page.

Looking them over, I’m actually a bit surprised the performance hit isn’t greater. But when I look at the summertime example, I’m also aware these are book numbers, requiring excellent technique. Having flown the Debonair for some recent near-gross takeoffs in hot weather, I know my technique isn’t perfect. But it is pretty good, and I also know the runway where the airplane is based now would be marginal for this scenario.

A couple of other observations include the difference in density altitude, 5000 feet in these examples. Initial of climb obviously takes a hit in the summer scenario, but not as much as I expected, frankly. A final observation is that the airspeeds for both operations are the same, as they should be since they were calculated at the same weight. That’s a reminder that, although the summer air is less dense, our airspeed indicators, because of the way they work, always directly display the speeds we need to know for takeoff and landing, no matter how hot it is. It just takes longer to accelerate to them in the summer.

Run the numbers for your airplane, whether with an app like this or the old-fashioned way, with your POH. Be honest with yourself, so you won’t be too surprised when you do it for reals.

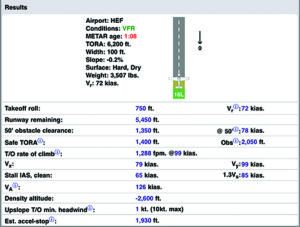

At right are the takeoff performance results I get from the Bonanza Performance app set up for my Debonair. I purposely “loaded” the airplane for this example, with three people, full fuel and some bags, resulting in a takeoff weight of 3507 pounds, 43 pounds below maximum gross. I used my old home base of the Manassas (Va.) Regional Airport/Harry P. Davis Field (HEF), as the departure airport (since Florida doesn’t get cold enough). Wind was zeroed out and I used the same runway for both estimates, Runway 16L. The only thing I changed between the two examples was the outside air temperature (OAT).

As labeled in the top example, I set the OAT to -7 degrees Celsius/19 Fahrenheit, a reasonable occurrence for winter in the area. Even at close to gross weight, I would need only 750 feet to lift off, and 1350 feet to clear the FAA-standard 50-foot obstacle. Accelerate/stop distance is 1930 feet, well within the available pavement.

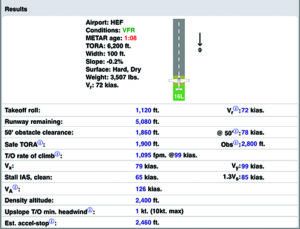

The bottom example was set up at a not-uncommon-for-Manassas OAT of 35 degrees C/95 F. While not as bad as I though it would be, especially on HEF’s long runway, it’s still a performance hit. Not shown in calculations like this, of course, are the higher airspeeds and reduced rates of climb sometimes necessary to help keep things cool. And poor technique, like mine, will increase all the runway performance numbers even more.

CONVECTIVE ACTIVITY

Summer obviously is when we most often encounter thunderstorms. Depending on where you live, they can be dark, monstrous, anvil-shaped beings strolling across the countryside, spitting hail, with aluminum-shredding turbulence plus the odd tornado, and blotting out the sun when you get close to them. They also can be much smaller, orphaned puffies that almost look cuddly from a distance, moving little and seemingly doing little more than wetting things down.

Don’t be fooled by one of these singleton’s benign appearance—you want to stay out of either kind, and preferably the FAA-approved 20 miles away. In fact, there’s no such thing as a benign thunderstorm, and you should do everything you can to avoid getting close to one, much less inside it. It’s admittedly easier to avoid the orphans, since they usually don’t take up as much airspace and aren’t as fast, but sometimes storm movements can work in your favor. Regardless, avoidance is key, and today we have a lot of pre-flight and in-cockpit tools available to make that task easier.

The color-coded Nexrad weather radar available from the FAA’s ADS-B In-based flight information system-broadcast, FIS-B, and providers like SiriusXM have been a boon to anyone trying to cover ground in the summertime. Displaying this information should be ubiquitous in any airplane even casually used for travel these days.

As good as these tools are, it’s important to remember a couple of things. First, all this stuff is advisory; you’re the pilot in command and flying into a thunderstorm should be on your “Do Not” list regardless of what an app displays on your consumer-grade tablet. Second, what appears on your iPad can easily be 20 minutes old by the time you see it, thanks to the time it takes to process the raw radar data, format it into something your software can use, send it to your receiver and wait for it to refresh. In other words, what you’re seeing on the display is history. What you’re seeing outside the cockpit is in real time, and its color-coding isn’t as starkly obvious as what’s on your display.

Third, and perhaps most important, if you remain in visual conditions and never enter a cumulus cloud, you’ll also avoid flying into a thunderstorm. That’s not to say you won’t get your hair mussed, though, and the closer you are, the greater the chance of encountering turbulence. It’s best to slow the airplane to at or (preferably) slightly below the published turbulent-air penetration speed, which usually is the airplane’s maneuvering speed, VA, before you get too close. If all else fails, see the sidebar above for what the FAA suggests if you enter the belly of the beast. But take action to avoid the storm, reverse course and go back the way you came, or divert to a suitable airport before any of that happens.

According to the FAA’s Advisory Circular AC 00-23C, Thunderstorms, these are a few of the steps you should take before entering a thunderstorm:

- Tighten all belts and secure all loose objects.

- Choose a course and altitude to take the aircraft through the storm via the shortest route below the freezing level or above the level of -15 degrees C OAT.

- Activate pitot heat, plus carburetor heat, turbine engine anti-ice or alternate air.

- Set pitch and power to maintain level flight at an airspeed below the airplane’s turbulence penetration speed.

- Turn up cockpit lights to minimize temporary blindness from any lightning.

- Disengage the autopilot’s altitude and/or speed-holding modes.

- Keep your eyes on the flight instruments.

- Don’t change power settings; maintain the recommended turbulence penetration airspeed.

- Maintain a constant attitude, allowing altitude and airspeed to fluctuate.

- Once in the storm, don’t turn back. A straight course most likely will get you through more quickly while turning maneuvers can place additional stress on the aircraft.

Above all, fly the airplane.

PLANNING

For obvious reasons, it’s always a good idea to fly earlier on a summer day than later. Frequently, though, we have a multi-leg route to fly with at least one fuel stop followed by a heavy, midday departure in our future. This is when some basic planning smarts can come in handy.

Weather is always your first concern when planning such a day, and it’s often useful to assess your route a few days early, comparing it to the prognostic charts for its viability. Will there be a summer cold front spawning storms that you’ll have to get past? (Pro tip: Land short of the advancing cold front, put the airplane in a hangar and your feet up in the FBO, and let the line of storms blow through before continuing your trip.)

What’s the forecast at your fuel stop? Maybe price shouldn’t be the only factor in choosing your fuel stop? How hot will it be and how will that affect your climb capability later in the day? Did you check the fuel-stop airport for any published departure procedures, especially obstacle-based, with minimum climb rates that may be marginal for your airplane?

Stale, humid and warm air of the kind that hangs around for days in the summer usually gets hazy in the bargain, sometimes drastically reducing visibility. It often can become a limiting factor if you’re not instrument-rated or current. As it reduces flight visibility, widespread summer haze also helps obscure obstructions, like mountain ridges and, especially, antennas.

The FAA’s Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (FAA-H-8083-25B) has some intelligent advice on how heat and subsequent dehydration can be minimized:

• “Flying for long periods in hot summer temperatures or at high altitudes increases the susceptibility to dehydration because these conditions tend to increase the rate of water loss from the body.”

• “The body normally absorbs water at a rate of 1.2 to 1.5 quarts per hour. Individuals should drink one quart per hour for severe heat stress conditions or one pint per hour for moderate stress conditions.”

• “If plain water is not preferred, add some sport drink flavoring to make it more acceptable. Limiting daily intake of caffeine and alcohol (both are diuretics and stimulate increased production of urine).”

• “If the aircraft has a canopy or roof window, wearing light-colored, porous clothing and a hat will help provide protection from the sun. Keeping the flight deck well ventilated aids in dissipating excess heat.”

PHYSIOLOGICAL EFFECTS

I’ve long felt that the lack of air conditioning aboard the vast majority of personal aircraft has been a factor limiting general aviation’s growth throughout the years. The non-flying public, accustomed to airliners, expects a/c in a machine costing well north of the car they drove to the airport. And while there’s no data of which we’re aware, it wouldn’t surprise me the least bit to learn that high temperatures are a factor in pilot-related accidents.

Especially during ground operations and at low altitudes, summer heat can affect our own ability to perform, just as it is detrimental to the airplane’s. Excessive heat increases our fatigue, dehydrates us and can distract from important tasks, like putting the landing gear down at the right time. And I can’t count the number of times my hands have been too sweaty to properly grip the yoke or some other cockpit control. The sidebar above has additional details, including suggestions on what to do and what not to do.

I always try to carry some cold water for me and my passengers, often in a small soft-side cooler. Consuming lots of water to stave off dehydration creates another problem: the need to urinate. There’s nothing safe about the need to relieve ourselves while flying an airplane. More-frequent stops may be necessary in the summer, if we plan to keep ourselves and our passengers happy and healthy.

AT THE END OF THE DAY

One of the good things about summer flying is the cooler air of late afternoons and evenings, especially after a rain storm has come through and the wind settles down. Few things are better for the soul than shutting down in front of your hangar after an evening flight and listening to the engine tick as it cools, along with the odd cricket, and watching the sun set with a cold drink in your hand.

If I have a choice, I prefer flying in the winter. The engine runs cooler. I run cooler, and I can layer enough clothing to keep warm, even without the feeble cabin heating system in the typical GA airplane. But summertime flying can be just as enjoyable. Plan your route and performance, avoid thunderstorms and take care of you, plus the passengers in your care.