In unguarded moments, many pilots will confess to what has come to be called “mic fright”—fear of talking on their aircraft’s radio. There may be many reasons for this aversion, but there is no way to avoid voice communication by radio if one plans to be an accomplished pilot. While those working to improve their radio use too often are focused on saying the wrong thing and being embarrassed, many other pilots fail to consider their role in the second part of ATC communication: listening. Actively listening to ATC when using their services is an often-neglected part of perfecting your flying skills. Look at it this way: To accurately receive a message, we need to listen for, hear and understand its contents. Actively listening is an important part of aviation, just as it is in our personal lives as well. So, what does it mean to actively listen?

In short, active listening is a conscious effort to hear and understand the complete message being conveyed, rather than just passively hearing the words of the speaker. This task sounds easy; many of us think we are listening, but it often turns out we merely hear what people are saying and don’t comprehend it.

The idea for this article stems from a flight school asking me to come down to teach one of their students how to actively listen while flying the aircraft. If you or someone you know has an issue with listening to instructions from ATC or traffic calls during flight, the following might be beneficial.

“Mic fright”—fear of talking on the airplane’s radio—is a real thing for many people. Although it’s possible to obtain an FAA pilot certificate without using a radio, doing so also imposes severe limitations on its utility. For those in search of additional information on aviation voice communications, the FAA offers its Pilot/Controller Glossary, which is available free for the download. The January 30, 2020, edition (PDF) is available at tinyurl.com/SAF-PCG.

Once you understand the words ATC uses and what they mean, the FAA’s Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM), Chapter 4, Section 2, is a great next stop. Going beyond the mere words common to aviation and what they mean, this guidance walks through the “etiquette”—the phraseology and techniques—of ATC communications.

Additional guidance is available from AOPA and its “New Pilot’s Guide To ATC Communication,” available on the association’s web site at tinyurl.com/SAF-ATC. One of its features is a list of words commonly used in aviation radio communications—especially with ATC—and explanations of their meaning in this context, plus how to use them.

Finally, a good resource for anyone wanting more experience with ATC communications is to listen in. The frequencies aren’t encrypted and it’s still legal to listen to other than the AM band with an appropriate receiver. Depending on how close to an ATC facility you are, you may only hear the airborne side of communications.

But the best resource we’ve found is LiveATC.net, a web site with free ATC audio feeds from a wide variety of locations. You can listen live or to archived audio, maybe even hear yourself on the radio. How does that sound? — J.B.

FIRST OF A KIND

This was a unique approach. In my years of involvement in aviation, I have never experienced a flight school going so far out of its way to help a student. As I got to know this student pilot, I found English was their second language, even though they had been proficiently speaking it for the last 20 years. As I interviewed them, we determined they are unable to engage in active listening while in flight over an unfamiliar area.

Due to this fear of the unknown, they focused on flying the aircraft instead of participating in the act of listening. They were so focused on their fears that they were unable to process the information being relayed by ATC. Once we discovered the root problem with fear of emergencies, we talked about ways to calm down and to relax during flights. The first thing we talked about was to sit back in the pilot seat and take a breath. If a student seems to be hunched over, they are usually focused on a single item, or experiencing tunnel vision. The reason for this tunnel vision is the same as when radar controllers stare at the radar scope: It’s busy and they do not want to miss anything.

With the advent of ADS-B, call signs now must be reflected in the identification information transmitted to ATC by complying aircraft. For most of us, our call sign is the aircraft’s registration number, but air carriers and the military have their own, and GA flights may sometimes desire a discrete call sign. To do so, however, they must be operating ADS-B Out equipment allowing crews to change the call sign to match the flight number.

We made a second discovery when the student was asked to practice scanning the instruments in a simulator. We noticed they were turning their head while looking at the instruments, resulting in dizziness. When I and the student’s flight instructor pointed this out, the student’s flying skills began to improve almost instantly.

Lastly, during this sim session, I stood behind them to simulate ATC instructions. I noticed they missed simple “transmissions” during times when multiple things were going on. After I used two techniques to improve active listening while they were flying the sim, they started to improve their listening and readbacks became faster.

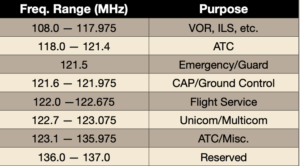

Although ATC communication with aircraft has evolved to include satellites and data-only services, most of it is conducted via voice on a conventional radio frequency. In the U.S., aviation users are allocated the frequencies 108.0 MHz through 137.0 MHz. Frequencies below 118.0 MHz primarily are for ground-based navigation; the rest are used for voice communication.

Also in the U.S., frequency spacing of 25 kHz has been implemented, requiring three digits to the right of the decimal point and offering up to 760 voice channels (includes nav frequencies). In other countries, especially Europe, 8.333 kHz spacing is used. Earlier communications radios, like the King KX 170 pictured at right, offered only 50 kHz spacing for 360 channels.

The table at lower right highlights some of the principal groupings of radio frequency allocations in the

MY WAY, EASY WAY

The two methods I used were simple listening games. The first game was that I would have the student sit across from me. As we talked, they would write down a call sign, heading, altitude or speed every time I mentioned one of them in our conversation. The activity had clear expectations and was done in a friendly, talking manner where I would continuously talk for about three to five minutes about aviation. I made an answer key before the meeting, then I would check off which ones the student had missed. After initial grading, it was not a perfect score, but we both had more detailed information on areas that could stand improvement, and a better understanding why.

It’s legal to operate at a non-towered airport without talking to anyone. It’s perhaps not the smartest thing to do, however. If everyone is flying the same pattern at the same speed, problems are unlikely.

But when there’s a mix of slow and fast traffic and different skill levels at a non-towered airport, self-announcing your position and intentions—and working out potential conflicts with the other pilots—demands good radio etiquette and concise phraseology.

Personally, I don’t need your N-number; just the type. Use common references, like “five miles south for the left base to Runway 27.” Be informative, but don’t dominate the frequency. And use the correct one.— J.B.

The second method I used was during a simulator session. I was standing behind them and with clear expectations using numbers one through 10, I would give them simple math problems. This engages the mind so that you are listening and responding at the same time. We all grew up with the idea that the best time to listen is when everyone is quiet. However in the aviation world, things are not that simple and multi-tasking—to the extent humans are capable—is the order of the day.

Controllers and pilots alike must be able to talk and listen simultaneously. Controllers usually have someone on the landline, there’s another controller coordinating and they’re talking to airplanes at the same time. If you chose to do this with a student, you would find the first few attempts humorous. What you would be looking for is that the student will end up stumbling over their words. After a few additional math problems, you will see the student begin to improve and be able to talk to you while giving you the answer at the end of the sentence without a pause. It’s essentially a matter of being confident in knowing what you are saying and being prepared to add more at the end of the sentence.

One source of problems some pilots may be having with their voice communications is literally not knowing what to say. The answers are not unlike the cub reporter’s mantra: who, what, where (and sometimes why and how).

WHO

This one’s a two-parter: Who are you calling? Who are you? On an initial call-up especially, it’s suggested you state the facility’s name, just in case you’re on the wrong frequency. It also clues the controller he or she has a new customer. Of course, they need to know who you are, too,

What

What type of aircraft are you? What do you want? Are you a student pilot? Something like this fills the bill: “Podunk Tower, November 12345 is a twin SkySmasher, 10 miles south for landing, student pilot.”

Where

The controller needs to know where to look for you and where to expect you to go next. Try to use familiar landmarks, which often are charted, or distance and direction from the airport in question, or from a navaid.

LISTENING IS WHAT WE DO

In the end the student thanked me for helping them out. Not only did we rid them of the fear of emergencies, but we also helped them learn to remain calm and relaxed during high-workload situations. Simple exercises helped this student out greatly. They are now finishing up the private pilot training and expect the check ride next month.

Active listening is part of the air traffic controllers job. Most tower controllers have only a pen and paper when you call in for services. We quickly write your information in shorthand, listen for your position, ATIS code and think about the instruction we will give you. Radar controllers type as they give control instructions to the pilot. Radar controllers must keep each data block up to date as each clearance is given.

An old trainer once told me that controllers should be able to write and talk, talk and listen, listen and scan. Practicing doing so is challenging but makes the job extremely easy if the skill can be mastered. Being able to balance of all tasks of flying is not easy for the new student but with time, practice and patience, every student has the ability to master the skill of active listening. Safe flying!