When I began my ab initio training, it seemed to take forever to get off the ground. Working through the preflight, before-start, run-up checklists, step-by-step in the order provided seemed to take up a lot of time I wanted to spend airborne. Of course, with practice comes efficiency. Eventually I would complete the steps in the checklist by memory, and then verify they were complete using the checklist. Cut to my first job flying and there was a name for this method of checklist usage: flows.

WHAT ARE FLOWS?

Different companies and flight schools have different terms for types of checklists, but for the sake of this discussion I will keep it to two types: challenge-response and do-verify. Challenge-response involves doing the checklist line by line, similar to how I used to complete checklists during my initial training. There is a time and place for this method. A good example is preflight, where distractions can be mitigated and minimal time pressure exists. Do-verify involves completing the steps in a certain order and subsequently confirming everything is complete with the checklist. For the context of this article, the first step of the do-verify is the flow. The FAA does not define flows or publish generic guidance on them, but essentially they are a memory technique for completing checklist items or ensuring that the aircraft is configured appropriately for a given situation.

So far, I have associated flows with checklists and normal flight operations. Their usage can extend to normal or abnormal situations. Many aircraft publish memory items, which should be practiced and memorized as flows. Additionally, I would consider flows to include memory-aid techniques such as the ever-famous GUMP check many use to ensure landing configuration in complex aircraft.

One thing many pilots think about when the subject of cockpit flows comes up is that you’re abandoning the checklist. For many reasons, that’s not the case—at worst, you’re performing a separate check. And you’ve been doing at least one or two flows on almost every flight since you started training.

The best example is the proverbial GUMP check we (should) perform before every landing. “GUMP” stands for Gas, Undercarriage, Mixture and Prop, four major items we need to check and/or position before every landing. There’s a before-landing checklist tucked away at your knee or in the POH/AFM in the copilot’s seat-back pocket, but the GUMP check covers the big items, to be followed up by using a more-formal checklist.

Same thing for CIGAR, which stands for Controls, Instruments, Gas, Attitude (flaps/trim/etc.) and Runup/Radio, prior to takeoff or even prior to taking the runway. — J.B.

BENEFITS

I spoke earlier about transitioning from challenge-response to do-verify as I gained more experience. As I grew comfortable with this method, I saw two benefits. The first was everything was double-checked. I ran through the items, and then confirmed everything was in order using the checklist. Secondly, interruptions became less of an issue. If I read a checklist item that requires a step or two, it was easy to get distracted and lose your place. Either you end up restarting the checklist to ensure a step was not missed or you push ahead and hope for the best. (Not that I have ever forgotten a checklist item this way, but I have certainly heard of it happening.)

Eventually, I saw more benefits. I grew comfortable with the aircraft in a number of configurations, so if a switch was missed or inadvertently pressed, it was easier to catch. If a non-standard situation popped up, or something had to be done out of order, it could be quickly accomplished without losing situational awareness of the flight path. Now I can picture many pilots out there flying a Cub on floats who have no need for this diatribe on checklist usage, but in my experience it’s the pilots who are a little relaxed with checklist usage who utilize flows the most. Consistent checklist usage is still the best bet to mitigate risk.

As I try to discuss risk mitigation techniques, I often notice how some of these techniques result in opening up new avenues for risk. Something that is important to remember is overall reduction of risk is the end goal, so do not let the perfect get in the way of the good. In this case, the biggest downside in my experience is checklist complacency. See the sidebar on page 15 for ways to combat this.

DESIGNING FLOWS

Maybe it is just the huge aviation nerd in me, but developing a flow is actually a fun process. Initially, whenever I am flying a new aircraft, I see if the manufacturer has any published memory items. Then I sit in the aircraft and chair-fly the procedure, seeing how the patterns look. The flow for engine failures in the Skyhawks I flew during my initial training was a backward-shaped L, beginning at the floor-mounted tank selector and ending with the ignition at the instrument panel’s lower left. This allowed easy memorization of a five- or six-step procedure, and more importantly, it is something that can be easily recalled in times of extreme stress.

Once the memory items are taken care of, it’s worth reviewing the other abnormal and emergency items. Some items, like anything involving smoke or fire, should probably be committed to memory whether it be a flow or acronym. It may seem like I am pushing for a lot of memorization, but it is strategic.

For example, during a flight review, I don’t ask applicants to recite each and every airspeed they may use. If there is a placard or marking on the ASI (and the applicant knows about it), that’s good enough for me.

Memory can be a tough thing, though. How often do we study for an event (like a written test or checkride), complete that event, and then experience the proverbial brain dump? Some may be able to juggle all those numbers and procedures, but I sure can’t. So we save that precious processing power for no-time items.

Like the aforementioned smoke and fire, some procedures need to be done immediately to prevent emergencies from getting any worse. Additionally, that situation may lead to your hands being too full to even reference a checklist. Combined with the stress a true emergency presents, a well-designed flow can be life-saving.

A good thing to pair with the flows you develop is a trigger: An event that normally occurs, which should remind you to complete a task. For example, abeam the numbers on downwind might be a good time to consider the aircraft’s gear and flap configuration. It’s not a radical concept: The commercial checklist at right and most of them in your airplane’s POH/AFM are organized around various flight phases. Here are some triggers and flows I use.

ON THE CLIMBOUT

After I have complied with ATC’s initial clearance or I have reached the point in my climb where the workload feels manageable, I will complete my climb flow and run any climb/after-takeoff checklists.

CRUISE

Cruise is sort of a gimme, but checking a few things when you level off at cruise can be lifesaving, or at least headache avoiding. By checking, I do not mean glancing. I mean looking critically at each system to ensure everything is operating normally, with the goal of finding even a small anomaly. Since this is the lowest workload time of the flight, time can be dedicated to checking the fuel, engine, electrical and navigation systems. Is the fuel where you expect it? Has the ETA changed substantially? Catching these threats early opens up the door substantially when considering alternate options.

TOP OF DESCENT

This is where I try to catch myself from falling behind the aircraft on approach and landing. Obviously a VFR pattern is less workload than a complicated instrument approach to minimums, but it is always a threat to enter the pattern behind the aircraft. The TOD trigger offers a chance to stop this before it even starts

500 FEET

Last chance check. Is the aircraft properly configured to land? If not, this is your chance to avert disaster. I actually call out 500 feet, which keeps me aware of my altitude (Can you tell I trained at sea level?) and also helps remind me of the MSA if applicable. This check should be ingrained for anyone who wants to mitigate the threat of a gear-up landing.

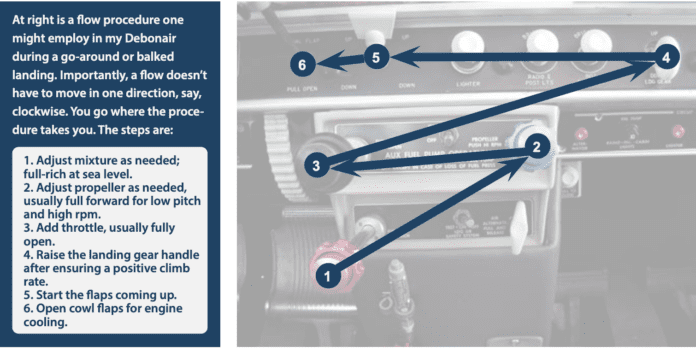

FOLLOW THE SEQUENCE

A good flow moves through the cockpit in the most sequential order possible. This might not always be easy, because steps that need to be completed in a certain order may jump around. But if you can make a pattern, and that pattern ensures all the steps are completed and indications are checked, it will be a lot easier to complete in a timely fashion and it will stick more readily than memorizing the steps one by one.

Another benefit is you can design flows that consider two different outcomes. For example, in one of the aircraft I flew, there was an engine troubleshooting flow that took two different steps depending on the fuel flow. If there was still fuel flowing, we would take Path A. Otherwise, Path B would be appropriate.

Now, flows can be used for more than just abnormal and emergency situations. The nice thing about flying your own aircraft is you can design your own checklists and procedures. Using the manufacture’s guidelines, you can design a flow that makes sense for your cockpit layout and the way you fly.

An example of how I implemented a flow that saved me a lot of headaches more than once was a quick pre-preflight. I knew that once I dropped my bag off, if I had to add oil or there was a major issue—such as tire damage, bird strike, etc.—it would take some time to resolve, and so I should take care of it sooner than later. So before even entering the aircraft, I would check the engine oil level and ensure no major damage occurred to the aircraft since it was last flown. If I found a low oil level, I knew I would have to allocate time to find a ladder and grab oil from the hangar so the aircraft stayed properly stocked. Obviously, a low oil level in some airplanes is a lot quicker to solve, but the example stands. I essentially worked in an extra walk around, outside of requirements of the company or manufacturer, strictly for my convenience. The convenience also prevented me falling behind during the preflight, which I personally find helps prevent rushing.

When I was a kid I noticed at the local theme park, before every ride began, all the staff around the boarding area would give a thumbs up and rotate it around the whole area. I used to think it was just a fun way to say all clear, like, “Thumbs up! See, good to go!” Now I realize that it is a technique to ensure the folks doing their safety checks actually look around the area and clear it for hazards. It is a good idea, because if they simply moved their head from side to side it would be extremely easy to miss something, especially performing the same safety checks again and again and again and again. As pictured, an aircraft carrier’s flight deck is a good place to use this practice.

Pilots can succumb to this same human factor. Outside of the normal jokes we could tell, how can you tell someone is a pilot? Say, “Positive rate.” If the person automatically responds, “Gear up,” you have found another pilot. Checklists and flows can fall victim to confirmation bias, we expect the flaps to be set so when we check them we glance over and miss the fact that they were set…last flight. This is why I point at each item when as I complete my checklist, especially if it is a do-verify. I do the checklist items with my flows, and verify by pointing. It slows my pace down, and I noticed I caught and trapped a lot of errors with this technique.

FINAL FLOW

While thinking about and conceptualizing this article, I thought of all the different flows I have used in the different airplanes I flown. Some were self-taught, others were company requirements and many I picked up as recommendations from fellow pilots. Usually they were the result of missing something or optimizing a procedure after experience in an airplane.

This is another reason why I always advocate flying with others when the opportunity comes up, and it does not have to be with someone more experienced that you. I often learn a new technique from a pilot fresh in a new role, especially considering the potential for new perspectives. Additionally, it is always a good idea to perform some small after-action report when a mistake comes up.

Like most of us, I am still waiting to fly the proverbial perfect flight. Since it has not happened, each flight presents a learning opportunity. If you find yourself the victim of not verifying something or forgetting to flip a switch, consider adding a flow to your toolkit to prevent the mistake from happening again. It is a great way to keep working toward that (probably impossible) perfect flight.

After a career as a Part 135 pilot, flight instructor and check airman, Ryan Motte recently got hired by a major airline and is now flying as a Part 121 first officer.

I may have given the “perfect” part 135 VFR checkride to a young flight instructor while I was an FAA ASI. The flight was in a non-autopilot CE-172 and the applicant confidently performed the walk around using a commercially produced plastic checklist. He was very thorough but his procedures in the cockpit were what impressed me the most. He used a do-it, check-it routine, verifying each action he performed by referencing the checklist.

Once underway, he stuck the checklist into the plastic door frame over his left shoulder. For every item that required a check, he would perform it, then reach up with his right hand, pull down the checklist to verify, then return it to its overhead position. VFR 135 checkrides still require an applicant to perform an instrument approach but his cockpit organization made it look easy, even without having an autopilot to help out.

I have to believe that this young instructor produced some very fine pilots.