On April 2, 2021, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia issued a response to a petition that concludes, in relevant part, that compensated flight instruction constitutes carriage of a person for compensation, possibly giving rise to the FAA’s commercial operating regulations (e.g., FAR Part 135). According to a joint letter to the FAA from AOPA, the Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA) and the General Aviation Manufacturers Association (GAMA), the court’s judgment creates “significant confusion and concern in the aviation community regarding the impact of the decision on compensated flight training, in limited category aircraft” and others. The unpublished decision, while not setting a precedent, could be used to fundamentally alter the legal basis for flight instruction in any kind of aircraft.

In its judgment, the appeals court found that FAR 91.315 does not provide an exemption for limited category aircraft to be used for flight instruction. Its reasoning, at least in part, is that FAR 91.313, regarding restricted category aircraft, contains specific language allowing flight instruction and that the FAA “could have chosen to make an exception to this rule for flight instruction” but didn’t (emphasis in the original). Interestingly, FAR 91.313 comprises 744 words. By contrast, FAR 91.315 simply says, “No person may operate a limited category civil aircraft carrying persons or property for compensation or hire.” Flight instruction in limited category aircraft usually is conducted under an FAA exemption granted by the FAA. But not in the case of this denial of a petition for review of an FAA cease and desist order.

The facts of the case have some bearing, unsurprisingly. Warbird Adventures, of Kissimmee, Fla., operates a two-seat Curtiss P-40N Warhawk. According to the court, “In 2020, the FAA ordered Warbird to stop providing paid flight instruction in [the P-40N] because it was not certified for that purpose.” Instead and again according to the court, “after FAA inspectors advised Warbird that § 91.315 prohibits paid flight instruction in the P-40N, Warbird continued to use the P-40N for paid instruction” and “refused to disavow future use…for paid flight instruction, even after repeated communications from the FAA.” The agency issued an emergency cease and desist order against Warbird Adventures, which then petitioned the appeals court for review. Its response throws FAR 91.315 into confusion and raised the industry’s concern.

The joint letter from AOPA, EAA and GAMA to Ali Bahrami, FAA Associate Administrator for Aviation Safety, states, “In the interest of safety, the aviation community needs clarification regarding how flight training can be provided in various categories [of] aircraft in compliance with the regulations, including any distinctions based on compensation for the aircraft….EAA, AOPA, and GAMA respectfully request that the FAA clarify its policy to ensure continuity for continuation of flight training.” The organizations requested Bahrami’s “personal attention to help expedite a direct and final statement.”

For years, the NTSB has assembled and published what it calls its “most wanted list” (MWL), a group of 10 safety improvements its investigations indicate are needed across all transportation modes. For the 2021-2022 period, the NTSB recently updated its MWL and included two items related to the aviation industry: safety management systems (SMS) for all revenue-passenger flight operations and data, audio and video recording devices for all passenger-carrying commercial aircraft, including charter planes and air tours.

Both SMS and data/audio recording technology has been required of large commercial air carriers to varying degrees for some time. The NTSB’s addition of them to the MWL is designed at least in part to urge the FAA to take steps to require them aboard all for-hire passenger aircraft, and add video to the data they collect. Ultimately, adopting the NTSB’s aviation-related MWL items is up to the FAA.

NTSB: See-and-Avoid Limitations And Lack of Alerts Led To Midair

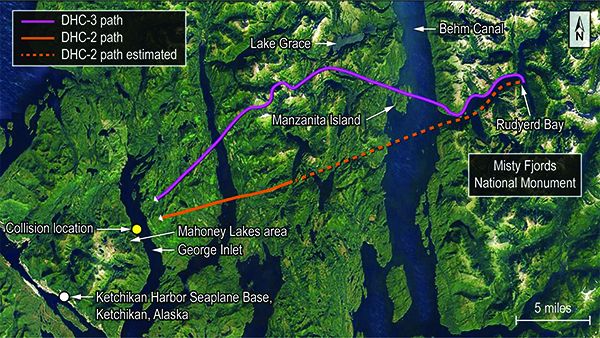

A May 13, 2019, midair collision of two de Havilland air tour airplanes resulted from “the inherent limitations of the see-and-avoid concept” and the lack of alerts from the airplanes’ ADS-B In traffic display systems, the NTSB said April 20, 2021, during a public meeting held to discuss its probable cause finding. The two airplanes, a de Havilland DHC-2 Beaver and a de Havilland DHC-3 Otter, both which were equipped with floats, collided at 3350 feet msl about eight miles northeast of Ketchikan, Alaska. The DHC-2 pilot and four passengers died; the DHC-3 pilot suffered minor injuries, nine passengers were seriously injured and one passenger died.

“From the earliest days of powered flight, pilots have been taught to avoid other airplanes by watching out for them,” said NTSB Chairman Robert L. Sumwalt. “This accident clearly demonstrates why that’s just not enough. Our investigation revealed that it was unlikely that these two experienced pilots could have seen the other airplane in time to avoid this tragic outcome.” The graphic at right shows the flightpaths of the two airplanes from the Misty Fjords National Monument area to the collision’s location overlaid on a Google Earth image.

According to the NTSB, “The lack of apparent motion of the DHC-2 when viewed from the DHC-3, and the obscuration of the DHC-2 by the window post for 11 seconds before the collision, made it difficult for the DHC-3 pilot to see the DHC-2 airplane.” Both airplanes were equipped with ADS-B Out and In. “Although the traffic display system installed on the DHC-3 depicted aircraft in the area, it could not provide aural or visual alerts to warn of a potential collision.” Meanwhile, “the pilot of the DHC-2 airplane had access to a traffic display system that could provide aural and visual alerts, but the DHC-2 pilot would not have received any such alerts because the DHC-3 airplane was not broadcasting required altitude information.”

Among its recommendations, the NTSB suggested that ForeFlight update its traffic alerting algorithms so that traffic targets lacking altitude information are assumed to be at the same altitude.