The FAA in February published a new rule designed to enhance professional development among air carrier pilots, with an emphasis on supplemental training for existing captains and more comprehensive indoctrination for new hires. The new rule becomes goes into effect April 27, 2020, although some of its various components don’t become effective for 24 or 36 months. The new rule is another response to NTSB findings that flight deck leadership can be improved.

“All captains are now required to receive leadership and command training, as well as mentoring training, so that they may effectively mentor first officers. Newly-hired pilots will be required to observe flight operations and become familiar with company-specific procedures before operating an aircraft as a flight crew member,” the FAA said in a press release. According to the rule, “…a problem still exists in the aviation industry with some pilots acting unprofessionally and not adhering to standard operating procedures (“SOP”), including the sterile flight deck rule. The NTSB has continued to cite inadequate leadership in the flight deck, pilots’ unprofessional behavior, and pilots’ failure to comply with the sterile flight deck rule as factors in multiple accidents and incidents….”

The final rule incorporates the work of the Flight Crewmember Mentoring, Leadership, and Professional Development Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC), the Flightcrew Member Training Hours Requirement Review ARC, and the Air Carrier Safety and Pilot Training ARC. All three ARCs, comprised of labor, industry and FAA experts, provided recommendations to the FAA. The new rule applies to flightcrew operating under FAR Parts 121 and 135, and those flying for Part 91 Subpart K operators.

Remember all the safety data you see in this magazine and elsewhere about accident rates per 100,000 hours of flight? Where does the underlying data on hours flown each year come from? It’s a product of a survey the FAA conducts each year, and it’s that time again. The FAA’s 42nd Annual General Aviation (GA) and Part 135 Activity Survey opened February 24 and runs to July 10, 2020.

The voluntary survey is distributed by mail to what the agency calls “a representative sample of GA and on-demand Part 135 aircraft owners and operators.” If you receive one and choose to participate, you can do so online or via mail.

The survey is four pages long and takes 10 to 30 minutes to complete, the FAA said, and it will publish only aggregated data so that individual responses are not identifiable. The process “fell down” in 2011, with the result that accident rates for that year cannot be calculated. So that safety and other metrics may be properly calculated, we encourage survey recipients to respond.

NEW AC REMINDS PILOTS OF COST-SHARING POLICIES

The FAA in February also published a new advisory circular, AC 61-142, which focuses on sharing aircraft operating expenses and the underlying regulations. The new AC is an additional response to the advent of now-defunct aircraft ride-sharing services like AirPooler and FlyteNow, plus BlackBird Air, that seek to operate much like terrestrial ride-sharing services Uber and Lyft but for private aircraft. As discussed in this space in our February 2020, issue, a variety of FAA regulations with which private pilots are not normally conversant—including FAR Parts 119 and 135—can come into play. Basically, the FAA takes very seriously FAR 61.113, which you already should know about.

The 12-page AC applies to “pilots exercising private pilot privileges who wish to share the costs of operating an aircraft during a flight with passengers,” the FAA says. Specifically, the AC “describes acceptable means, but not the only means, for demonstrating compliance with the applicable regulations.” Those regulations include FAR 61.113(c) as well as other Part 61 expense-sharing provisions, including FARs 61.101 and 61.315. Pilots and other entities looking for a way to bring Uber-like ride-sharing to aviation will be disappointed by the AC’s contents, which include an extensive description of various hypothetical-but-realistic situations in which pilots and aircraft owners may find themselves.

The NTSB in February called on the FAA to form a working group “to better review, prioritize and integrate Alaska’s unique aviation safety needs” into the FAA’s safety enhancement process. “We need to marshal the resources of the FAA to tackle aviation safety in Alaska in a comprehensive way,” said NTSB Chairman Robert L. Sumwalt. “The status quo is, frankly, unacceptable.” From 2008 to 2017, the total accident rate in Alaska was 2.35 times higher than for the rest of the U.S. while Alaska’s fatal accident rate was 1.34 times higher in the NTSB’s statistics.

The NTSB’s request to the FAA came as a result of a September 2019 roundtable the safety board convened. As one example of ways that risk-management analysis is applied to aviation, an air carrier official pointed out that the recent proliferation of instrument approaches throughout the state does them little good without local weather reporting. The question is whether adjusting FAA rules to accommodate Alaska operations would enhance safety.

The new AC provides detailed discussion of the three foundational elements in its ride-sharing policy: how expenses may be shared among the pilot and passengers, that there must be a common purpose for the flight and that certain activities—like participating in an “Uber-for-aviation” ride-sharing service—may constitute “holding out” to the public to provide air transportation services, a no-no for someone exercising their private pilot privileges.

Pointing back to FAR 61.113(c), the FAA says, “Receipt of compensation outside of the exceptions contained in § 61.113 is a violation of Part 61 subject to civil penalties. If the flight does not fall under the exceptions, the pilot may be found to be operating an aircraft as a commercial operator and must comply with the appropriate regulatory requirements for air carrier and commercial operations.”

The AC’s summary notes, “Pilots may share operating expenses with passengers on a pro rata basis when those expenses involve only fuel, oil, airport expenditures, or rental fees…. The ‘common-purpose test’ anticipates that the pilot and expense-sharing passengers share a ‘bona fide common purpose’ for their travel and the pilot has chosen the destination. Communications with passengers for a common-purpose flight are restricted to a defined and limited audience to avoid the ‘holding out’ element of common carriage,” the summary concludes.

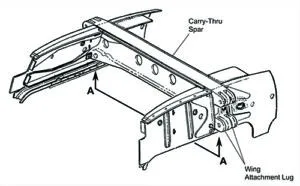

The FAA on February 21, 2020, published a new airworthiness directive (AD 2020-03-16) requiring visual and eddy current inspections of the carry-thru spar lower caps aboard some 1520 airplanes in the U.S. registry. Affected are Cessna models 210G, T210G, 210H, T210H, 210J, T210J, 210K, T210K, 210L, T210L, 210M and T210M, commonly known as a Centurion or Turbo Centurion. Earlier 210 models than these have strut-braced wings; later ones are not included in this AD at this time.

The problem? The airplanes weren’t treated with a corrosion preventive during manufacture and they’re, well, corroding. The newest of these airplanes left Wichita in 1980; the oldest in 1967.

A catalyst for the new AD is the 2019 in-flight breakup of a T210M Turbo Centurion in Australia. Examination revealed “fatigue cracking that initiated at a corrosion pit.” Much of what the FAA wants done is already covered by manufacturer service letters, although the new AD adds an eddy-current inspection to its requirements if any corrosion was removed.

“As of January 29, 2020, Textron has received 194 inspection reports on [affected models]. Of these 194 reports, 96 airplanes have reported corrosion (49 percent) with 18 of those reports (9 percent) resulting in removing the carrythru spar from service,” the FAA said.

The new AD goes into effect March 9, 2020, and requires compliance by May 8, 2020, 60 days later. It’s an interim action but feedback from the field will be used to determine subsequent FAA actions, if any.

NEW NTSB ALERTS ON KEYED SWITCHES, TWINS

As it does from time to time when it identifies a developing accident trend, the NTSB in January released two new safety alerts general aviation operators should consider. The new alerts, SA-080 and SA-081, respectively urge checking the ignition switch and key integrity of thousands of GA aircraft, and remind multi-engine pilots of the control difficulties one-engine inoperative (OEI) flight presents.

The ignition switch/key integrity issue the NTSB identified affect many single-engine piston-powered aircraft and is yet another inevitable consequence of operating older machines. Specifically, according to the safety board, “Over time, key-type ignition switches and associated keys can become worn such that it is possible to remove the key from a switch position other than the OFF position. A loss of ignition switch-to-key integrity can result in an ungrounded magneto, which could lead to unintended engine startup during hand movement of the propeller and possible injuries or fatalities if anyone is near or in the path of the propeller at the time.” The safety alert includes examples of engines starting without the key in the ignition switch, including a fatality, one with a serious injury and another resulting in damage to two airplanes.

Suggested actions include proceeding with caution around any propeller, verifying the switch’s integrity “to ensure that the key can only be removed from the ignition switch in the OFF position” and complying with service bulletins.

The NTSB’s safety alert on OEI flight operations doesn’t apply to as many aircraft, but it highlights a long-term problem with twins when one engine fails: they’re more difficult to control. This should not, however, be something new for multi-engine pilots: As the NTSB says, “Sadly, the circumstances of each new accident are often remarkably like those of previous accidents, which suggests that some pilots are not taking advantage of lessons learned that could help them avoid making the same mistakes.”

Recommendations include honesty about your ability to recognize and handle an OEI situation, especially during critical flight phases, familiarity with the airplane’s procedures and understanding how poor performance may be.