In a perfect aviation world, skies would always be clear, our engines would merely sip cheap fuel by the pint instead of guzzle it by the gallon, and the winds always would be right down the runway. That world, of course, doesn’t exist, so we’re forced to get an instrument rating, plan fuel stops and carry a live credit card, among other adaptations. We also have to learn to strike a balance between the runway’s orientation and whatever the wind is doing when we want to take off or land.

We call the difference between the runway heading and the wind’s direction a crosswind, examples of which have bedeviled pilots since Orville and Wilbur tossed a coin to decide who would be the first to fly their contraption. (I’ve always wondered whether the coin-toss winner got to fly or got to stay on the ground.) In fact, there’s something of an Internet competition among aviation buffs to come up with the gnarliest video of airliners landing in a crosswind. The entries are never-ending and some crews just aren’t getting paid enough.

But after 120 years of trying to coexist with crosswinds, it turns out that finding the right balance can be one of the keys to handling them when landing or taking off. Who knew?

DIFFERENT FLAVORS

A lot of people knew, actually, probably including your primary instructor. They tried to teach you some combination of crabbing the airplane’s nose into the wind and/or lowering the upwind wing and maintaining the desired heading with rudder, whether landing or taking off. The early results likely were ugly and haphazard, but before you were turned loose to solo, you had at least most of the technique down.

On paper, of course, crosswinds are relatively simple: The wind wants to displace your airplane sideways. Your job is to counter that tendency with judicious, appropriate control inputs, perhaps even including throttles when flying a conventional twin. And steady-state crosswinds are relatively simple: Once we’ve established a correction when landing, we should be able to hold it all the way onto the runway.

When taking off, the opposite is true: We start out with full aileron and appropriate rudder. As we accelerate, we’ll have to reduce aileron input while managing directional control. But not all crosswinds are steady, and it’s likely our speed will be changing, especially on takeoff, which affects our airplane’s control effectiveness.

Importantly, it’s not necessary to add knots to our target landing speed—or liftoff speed—if there are no gusts. A crosswind by itself isn’t license to abandon your normal airspeeds. The worst case is to add knots to our approach speed when landing on a short, narrow runway. There’s a real risk of running off the end of the runway if we’re not careful.

Finding and keeping the sweet spot of appropriate control deflection can be infinitely more difficult in gusty conditions. If we let it, that is.

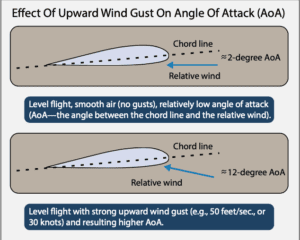

One of the main things about gusts is we don’t want one to exceed the wing’s critical angle of attack (AoA). We do so by flying at a lower AoA, and one of the ways we do that is to fly at a higher airspeed. The graphic at right shows what can happen to AoA in the event of an upward gust.

Conversely, the most common error when confronting gusty winds is to add too many knots to our approach speed. The rule of thumb is to add half the gust value to our desired final approach sped. So, for example, if our normal airspeed is 70 knots and the crosswind is 10 knots gusting to 20, the gust value is 10 knots and our gust-corrected target airspeed is 75 knots.

FINDING THE BALANCE

Another error is trying to “chase” the wind. Typically, gusts average themselves out over time. I’ve always found it worthwhile to extend my downwind leg a bit to set up a longer final, giving me more time to find the balance I’m looking for: the right amount of aileron and rudder deflection at the right airspeed for conditions. I often can set up aileron and rudder deflection values a mile or more from the runway and simply hold those control inputs all the way to touchdown.

At a relatively low speed and in a stiff, direct crosswind, like when starting a takeoff roll, we might need all the control deflection available to maintain the desired heading. Importantly, if full aileron into the wind and appropriate rudder input aren’t enough to maintain directional control early in the takeoff roll, it’s a sign the crosswind is too much for now. Regardless, as we accelerate, control effectiveness increases and we’ll need to relax some of that deflection. But if the airplane’s desire to weathervane into the wind can’t be controlled, we’ll need to abort the attempt and try again later.

The thing many of us forget, at least initially, is that the reverse happens when landing: we need more deflection as the airplane slows. In both instances, however, we’re trying to find the right balance of aileron and rudder input, with the idea of constantly reacting to the airplane’s changing speed and, perhaps, the wind’s changing velocity, to maintain runway alignment.

INTO THE WIND

Less-experienced pilots may get confused about control positioning when first confronting a crosswind. This also is true when learning to taxi in stiff winds. When considering crosswind landings and takeoffs, an important thing to accomplish is preventing the wind from getting underneath the upwind wing and lifting it beyond our ability to control the airplane. We do this by applying aileron into the wind.

If the crosswind is from the right, start the takeoff roll with maximum right aileron. As the airplane accelerates—and as you determine you can maintain control in these conditions—gradually roll out some of the aileron you’ve applied. If you’re doing it right, you’ll lift off in a slightly right-wing-low attitude. Once a positive rate of climb is verified, we can roll the airplane slightly into the wind, then relax aileron input to establish a wings-level, crabbed-into-the-wind attitude.

ROLL REVERSAL

Meanwhile, what are you doing with the rudder? When flying a single, things can get confusing. In a no-wind condition, we typically need some rudder input to keep the airplane aligned with the runway during takeoffs. An airplane with its single engine turning clockwise when viewed from the cockpit will need right rudder on takeoff when there’s no or little wind. With a crosswind from the right, we’ll start out needing right rudder input as full power is applied, but we may soon need to relax it or even apply opposite rudder as airspeed and rudder effectiveness increase, and we remove some of the aileron deflection.

EXTREMES

If we absolutely, positively have to use that runway in these conditions, there are some things we might be able to do, however. One of them is only doable with a conventional multi-engine airplane: differential thrust. Use the throttles to help maintain directional control by slightly advancing power on one engine or reducing it on the other, until either all the wheels are on the ground or we’re airborne. On long and wide runways, we can start the takeoff roll or aim for touchdown on the downwind runway edge and point it toward the opposite edge to minimize the crosswind’s effect. And, since the flight-control surfaces are more effective with higher airspeed, we also can opt to keep the airplane on the ground longer, beyond normal liftoff speed, and touch down faster, to ensure control effectiveness.

These and other maneuvers can require greater familiarity and experience with your airplane than may be typical, so it’s best to practice them in relatively benign conditions before doing them for real.

There are crosswinds we can’t or shouldn’t even try to handle. One reference we need to know when making such a decision is the airplane manufacturer’s maximum demonstrated crosswind component, which should be published in the POH/AFM’s limitations section. The trick with the max-demo’d crosswind value is that it’s not a limitation for CAR 3/FAR 23 airplanes. Instead, it’s advisory, and you can fly in conditions exceeding that value. Of course, if something happens, the FAA may want you to justify your decision at a hearing.

At the end of the day, there are conditions you and your airplane shouldn’t be in. When in doubt, or especially when running out of flight-control authority, go to another nearby airport featuring runways better aligned with the local wind conditions, and either park it for the day or wait for the stiff breezes to subside, then try again.

ERRORS

Of course, we all make mistakes. When dealing with crosswinds, one major error is to try correcting only with one or the other principal technique: crab or sideslip. In our experience, crabbing into the wind is only a good technique when well above the runway and there’s no risk of contacting it again in that attitude.

It’s always better to use some combination of crab and sideslip, except when touching down or lifting off. Crabbing into the wind while the wheels are on the ground can lead to all sorts of mischief, and rarely has a good outcome. At the same time, using aileron into the wind and coordinated with appropriate rudder input while on the runway maximizes control without skidding tires sideways.

Other errors include relaxing control input too soon or keeping it in too long. Relaxing our crosswind corrections too soon on landing can raise the upwind wing when we don’t want anything of the sort. Keeping the correction in too long on takeoff can drag a wingtip in extreme situations. Remember: we’re striving for balance here, something that feels like the airplane is on the head of a pin, but have the appropriate corrections dialed in perfectly. And we need to be able to keep them.

FINDING THE RIGHT BALANCE

Flying crosswinds can be very rewarding. Using all the flight controls, and possibly even throttles, while gently easing the airplane on and off the runway with the maneuver’s outcome never in doubt can be a confidence-inspiring thing.

But like anything to do with aviation, we have to know our limitations, which may or may not be those published in the AFM/POH. There’s nothing wrong with “taking a look” at crosswind conditions down close to the runway as long as we understand they may be more than we can or want to handle. Going around can be the right balance, too.

Jeb Burnside is this magazine’s editor-in-chief. He’s an airline transport pilot who owns a Beechcraft Debonair, plus the expensive half of an Aeronca 7CCM Champ.