The modern general aviation airplane has data flowing from it like never before. The flood started with digital engine monitors. Then electronic flight decks came along, capable of storing a vast array of information about each flight for later retrieval and analysis, which is especially valuable in a training environment. Now it’s ADS-B, which literally tracks our position, every heading change and altitude excursion with uncanny accuracy and—with the right equipment—for anyone to see.

Larger airplanes—business jets and airliners—have been installing digital flight data recorders (DFDRs) for some time, whether required or not, as well as quick-access recorders (QARs) which, as their name implies, are designed to provide operators with a similar source of data as the DFDR but retrievable without disturbing the required equipment. Analysis of QAR data by the operator has facilitated reconstruction of in-flight events, and using DFDR data to reconstruct accident sequences has provided government and operators alike key insights into how mishaps occur. If only all that data could be used to identify problems before they happened, and track the successes.

In the late 1990s, the FAA began its Aircraft Situation Display to Industry (ASDI) program. It was the first time near-real-time aircraft tracking information became publicly available, and Aviation Safety’s online sister publication AVweb.com soon began offering appropriate software through a partnership with a company known as Flight Explorer. At the time, the ASDI data stream depended on the FAA’s radar system network; today that’s been superseded by ADS-B.

Then as now, some operators didn’t care for the idea that anyone with an Internet connection could track their aircraft, so the agency, the ASDI industry and user groups, primarily the National Business Aviation Association, came up with a new program—BARR, for Block Aircraft Registry Request—allowing interested parties to block their data from appearing. Today, that has evolved into the FAA’s LADD program—Limiting Aircraft Data Displayed—allowing operators of ADS-B Out-equipped aircraft to keep their flights from being tracked over the Internet. Participation does not, however, prevent anyone with an appropriate receiver from obtaining the raw, unencrypted data ADS-B Out-equipped aircraft transmit.

To learn more about LADD and request participation, visit ladd.faa.gov.

INTRODUCING ASIAS

In 2007, the FAA contracted with the not-for-profit research and development management firm MITRE Corporation to develop and operate the Aviation Safety Information Analysis and Sharing program (ASIAS). According to the FAA, ASIAS is a “collaborative information sharing program” designed “to proactively analyze broad and extensive data sources towards the advancement of safety initiatives and the discovery of vulnerabilities in the National Airspace System (NAS).”

“The primary objective of ASIAS is to provide a national resource for use in discovering common, systemic safety problems that span multiple operators, fleets, and regions of the airspace,” MITRE says in a 2016 document titled “General Aviation ASIAS FAQs.”

According to a presentation by the FAA’s David Hughes to a September 2020 Air Traffic Control Association virtual symposium, ASIAS aggregates safety data “from 185 sources across industry and government, including 46 commercial air carriers and 21 corporate/business operators of jets, turboprops or piston aircraft.” Participants do so voluntarily and the supplied information is de-identified, aggregated and protected before it’s available to users. “The data collection allows safety researchers to compare multiple sources of information for a single safety incident. It also enables users to perform integrated queries across multiple databases,” Hughes added.

The FAA’s bimonthly Safety Briefing magazine chose “data” as the organizing theme of its September/October issue emphasizing that, as Rick Domingo, Flight Standards Service Executive Director, put it, “We all want to see the GA accident and incident rates decrease, and data is key to figuring out where the hazards are, and what mitigations we can take to eliminate them.” The magazine also quotes FAA Administrator Steve Dickson as saying, “We must continue leaning into our role as a data-driven, risk-based decision-making oversight organization that prioritizes safety above all else.”

As part of its approach to increase the flow of general aviation data into ASIAS, which the agency says first began in 2015, it created a framework to allow its collection, which led to the National General Aviation Flight Information Database (NGAFID). According to Safety Briefing editor/contributor James Williams, 118 business jet operators with traditional flight data monitoring programs have joined ASIAS.

The FAA is quick to stress that participation in ASIAS is voluntary and that submitted data “cannot be used for any enforcement purposes,” similar to NASA’s Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS). General aviation operators can participate in ASIAS by submitting data from on-board avionics or by using a newly developed app on a smartphone or tablet. Benefits include replaying your flights and using the data to identify potential safety risks while enhancing your skills.

To learn more about participating in ASIAS and to download the GAARD (GA Recording Device) data collection app, visit ngafid.org.

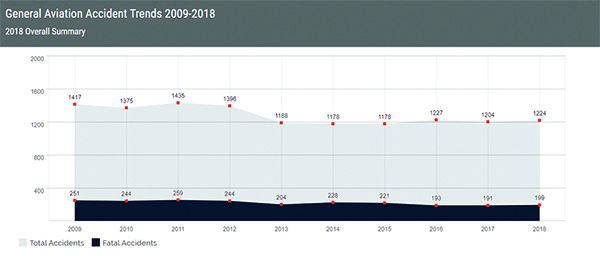

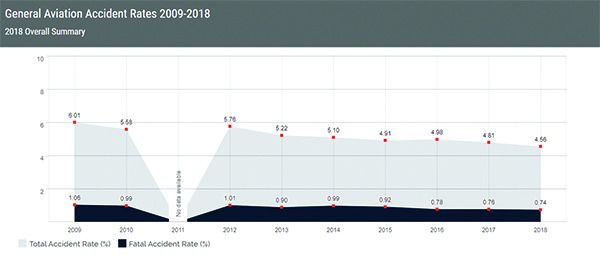

The AOPA’s Air Safety Institute in late October updated its annual Nall Report by releasing two editions—the 29th and 30th—simultaneously. Both reports follow and expand the online-only format AOPA/ASI implemented last year with the 28th Nall Report but offer an enhanced interface and what the organization promises will be “near-real-time accident data analysis as the data are updated on a rolling 30-day cycle.” Going online will do that for you.

“I am excited that this major effort has significantly accelerated the accident analysis process. This allows us to release the twenty-ninth and thirtieth Joseph T. Nall Reports, which provide a snapshot in time for 2017 and 2018 data, respectively,” said Air Safety Institute Senior Vice President Richard McSpadden. “In addition, the new interface allows anyone to select accident analysis graphs for multiple years, from as far back as 2008 to preliminary data trends for 2020,” McSpadden added. “The NTSB takes approximately two years to issue its final findings for accidents, so as we move into 2021, initial accident data rates will also begin populating for the year 2019.”

The two charts above detail accident trends from 2009 through 2018 plus the resulting accident rates. The good news is that, although the total number of accidents ticked slightly upward in 2018, the total accident rate for 2018 continued its downward trend. For more on the AOPA/ASI’s newest Nall Reports and a look at the data, visit tinyurl.com/SAF-Nall.

.