The first evidence of a retractable landing gear design was in Europe circa 1911, but a working example didn’t show up on aircraft until after WWI. As airplanes got heavier and faster, meanwhile, airport infrastructure—which mainly consisted of an open field and a windsock— couldn’t keep up. As a result, some of the fastest airplanes in the 1920s and 1930s were seaplanes, even with the aerodynamic drag their floats imposed. By the time WWII erupted, the latest airplanes were equipped with retractable landing gear, even if in a conventional, taildragging configuration. Still, many long-range, multi-engine airliners of the day were seaplanes.

Boeing and Lockheed, among others, introduced retractable gear in the 1930s, although many manufacturers didn’t fully enclose the main gear. In an eloquent statement of what the engineers thought about the reliability of retractable landing gear, they sometimes designed the system so the wheels would still roll, and protect the fuselage and engine nacelles, when landed gear-up. Thankfully, the technology has improved since then, if not the pilots.

Background

Retracting at least the main landing gear, of course, reduced drag and allowed for better performance, and greater cruising speed. A significant engineering problem at the time was the force or power required to retract the landing gear. In the early years, it was done either manually or with heavy electric motors on larger aircraft. Hydraulic power came into use when the O-ring was introduced back in the late 1930s.

Until retractable landing gear became common, wheel fairings were a popular way to try minimize the drag resulting from leaving the wheels dangling in the breeze. Fairings, wheel pants, spats—whatever they were called—were relatively cheap to make and weighed less than a retractable gear system with motors.

Landing off-runway may not allow first responders to assist you in a timely manner should there be a fire or if you are trapped inside the aircraft.

The grass beside a runway may be soft and/or irregular, allowing sod to bunch up and bring the airplane to an abrupt stop, perhaps inverted.

It’s likely landing on pavement will result in less aircraft damage than turf or sod. Either way, there will be repair costs, including a new prop, engine inspection and sheet metal.

Features And Operation

Without digging into the regulations on landing gear design, there are many safety features modern retractable gear aircraft all have. The sidebar on page 11 discusses them in more detail, but they include circuitry to help prevent the gear from retracting on the ground, some kind of alternate extension system, a warning system—often the same horn as the stall warning, but modulated—and landing gear position indicators of some kind. Operating limitations can include maximum airspeeds for retraction, gear down and extension. A recommended maximum speed also may be listed for the alternate gear-extension procedure.

Design features include the time it takes to retract the landing gear. This corresponds to aircraft performance considerations as in a climb over an obstacle in a specific distance, and associated single-engine climb performance for multi-engine aircraft.

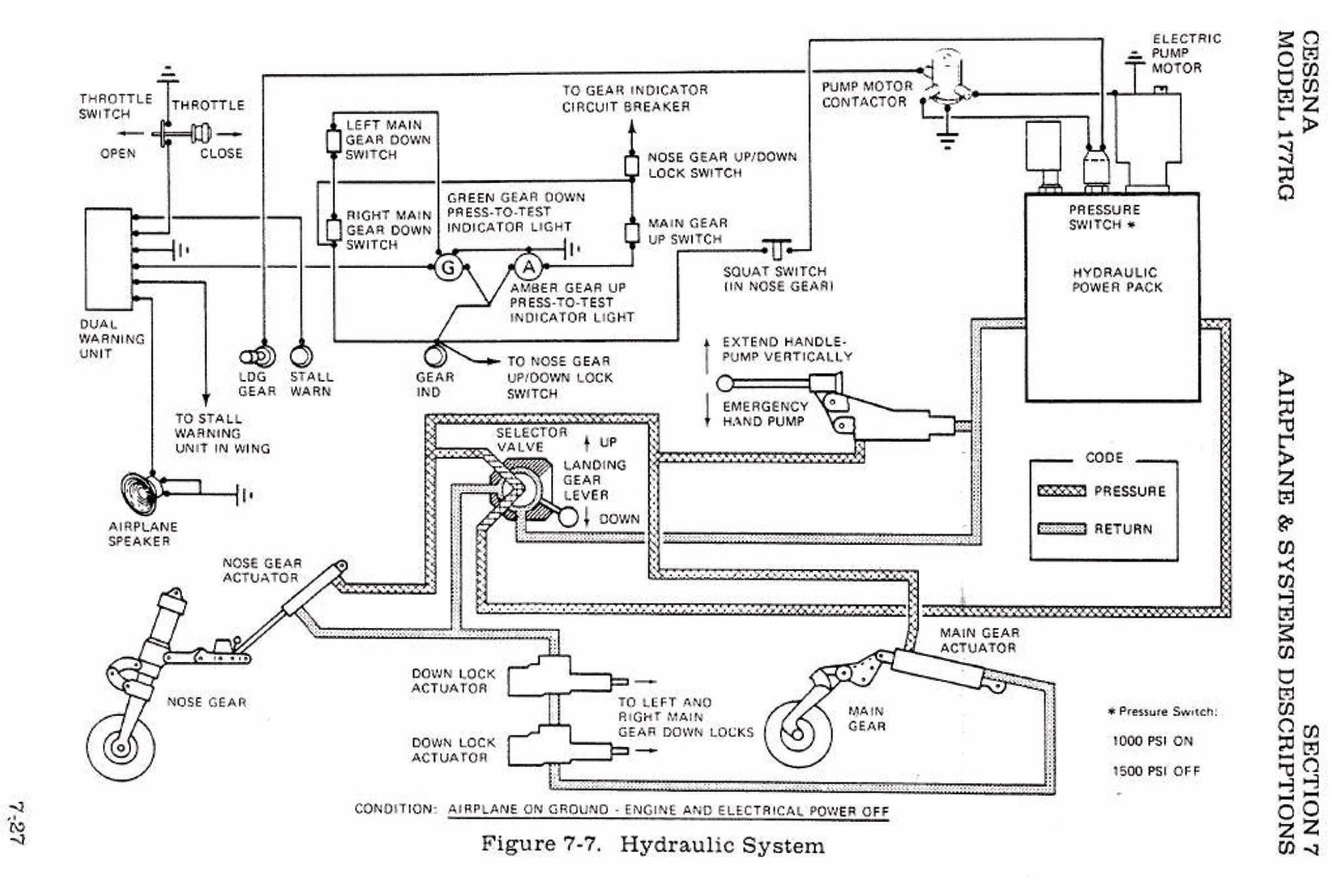

Meanwhile, there are several basic designs used to retract and extend landing gear. These can be electric-motor powered, as with Beech Bonanzas and Barons, based on an engine-driven hydraulic pump and incorporating a manual backup (early Piper twins) or employ a hybrid electric/hydraulic system (Cessna single-engine retractables, and the 337 Skymaster). A few aircraft, like early Mooneys, have a manual “Armstrong” method of extension and retraction—pilots use a long bar to lever the gear up and down (Hint: It’s easier at lower airspeeds). Yet another method is pneumatically operated landing gear (if found, it’s usually on a European or Soviet-bloc airframe).

Why so many different mechanisms and power sources? Reasons can include weight, available space in the wing or fuselage, a suitable power source or a combination that best suits the application.

Another example of an electric/hydraulic system is on Piper’s PA-28R Cherokee Arrow models, the PA-32R Lance/Saratoga series and the PA-34 Seneca variants. This system uses a two-position switch on the instrument panel, not unlike other landing-gear switches. In the Piper system, the switch controls a reversible electric motor. This motor is powered by the aircraft’s electrical system to operate a hydraulic pump used to pressurize hydraulic actuators.

This pressure retracts the landing gear with fluid flow in one direction while hydraulic pressure in the opposing direction is used to drive the gear down. When the gear reaches full travel, the electric motor is shut off by limit switches in the wheel well. Some variant of this basic design is incorporated into other electro-hydraulic landing gear retraction systems.

In Piper’s system, when hydraulic system pressure is lost due to a leak, the gear will extend, and is designed to freefall into the down-and-locked position. In the case of a failure of the electric motor or pump, the gear can be extended by moving a small lever that opens a valve to relieve all hydraulic pressure and allow the gear to free-fall. As the gear extends, aerodynamic loads and springs assist in the operation and ensure that the gear is held in the full-down and locked position without regard to positive hydraulic pressure.

To retract the landing gear, hydraulic pressure must be applied to initially release the down locks and then cause the actuators to move to the retracted position. Which means if there’s a hydraulic leak, it’s unlikely you can retract the gear. Still, that’s far preferable to being unable to extend it.

Another basic landing gear system is operated by an electric motor powering a jackshaft or other mechanism. On Beechcraft Bonanzas and Barons, the electric motor is attached to a transmission that mechanically moves three rods to retract or extend the landing gear. Especially important is the tension on the rods between the transmission and each gear leg. That tension may change due to worn rod ends or operation with improper tension causing rods to bend or break.

Aboard the Bonanzas and Barons, alternate gear extension is by a hand crank mounted just between and behind the pilot and copilot seat on the rear floor. Should the motor or the electrical system fail, the hand crank still can be used to extend the gear. Ensure on preflight that the hand crank is properly stowed yet accessible should the need for its use arise. The handcrank should not be used to retract the landing gear.

The downside of a mechanical system like the Bonanzas and Barons is if an operating rod breaks, there is no alternate method to fully extend the gear. The downside of a hydraulic system is when it loses fluid. Even the old Mooney Armstrong system could fail.

Regardless of what retractable you fly, to forestall failure and ensure reliability of any gear system, it’s best to complete a rigging check and overhaul the electric motor or hydraulic pump at specified intervals. Hydraulic hoses can fail and also have recommended replacement intervals. Proper lubrication throughout the system also is important.

Loose Nut Behind Wheel

Aside from the weight, complexity and maintenance requirements of retractable landing gear systems, one of their major drawbacks is that inevitably pilots will forget to use them before landing. Some say that there are two kinds of retractable gear pilots: those who have landed gear up and those who will. There’s some truth to that statement, but proper training and rigorous use of a pre-landing checklist—even if it’s just reciting GUMPS while checking everything—along with proper procedures can prevent gear-up landings.

Most of the time, personal aircraft landing gear retraction systems work just fine. When they don’t, there’s often a remedy you can apply by pulling out the correct checklist and methodically running through it. Of course, remember that you still have to fly the airplane while you’re doing all this. If all else fails, you’re going to land gear-up, which likely will damage the airplane but—if you do it right—you’ll walk away.

For example, how long does it take for your landing gear to go up or go down? What’s normal or abnormal? Is there evidence of leaking hydraulic fluid? Does the electric motor and/or hydraulic pump operate occasionally during cruise for no apparent reason? Do the gear lights sometimes flicker or go out during flight? Does the landing gear motor circuit breaker trip once in a while? These examples are indications that maintenance is required, so don’t overlook them with the idea they’ll fix themselves.

Have you thought about being forced to land gear-up if the alternate extension system fails? How will you proceed? While there have been discussions and opinions on the aspects of landing gear-up, there are some recommendations that seem to make sense. Given the options of landing with one wheel not extended and the others extended, is it better to land with all three gear up or better to land with two or one of the three down?

Landing with all three wheels up increases the odds of surviving a gear-up landing and minimizing damage, as the aircraft would most likely remain upright as opposed to dragging a wing and cartwheeling or flipping over landing with the nose gear up and mains extended. The important item here is to survive the gear-up landing and not to try and save the aircraft or engine/propeller.

On-Ground Switches:Also known as squat switches, these are designed to disable gear retraction when there is weight on the wheels. The electronic components are relatively inexpensive and easy to replace, but they do fail.

Alternate Extension System:It could be as simple as releasing a hydraulic valve or as energetic as hand-pumping or -cranking the gear down. If it fails, the insurance company just bought the airplane. Your job is to walk away.

Unsafe gear warnings:The worst situation is a main gear that won’t extend. You’ll likely lose control before coming to a stop. Best to retract everything and land on pavement.

Position Indicators:Some older indicators are mechanical, others electric. They all can lie at one time or another, but you’re more likely to ignore lights and horns than the system is to fail.

Mike Berry is a 17,000-hour airline transport pilot, is type rated in the B727 and B757, and holds an A&P ticket with inspection authorization.

I am doing a lot of check outs in a Cessna 172 RG of late.

One item I drive home to the candidate is to check the two nose gear doors are secure and that the down drive mechanisms are OK.

If one gear door is not secure then there is a good chance that the door will be blown up followed by the wheel which will get jammed and not come down when needed. Just an important thing to check on any retract gear aircraft