My Lancair IV-P recently had an engine “overhaul.” Well, not an “overhaul,” a “rebuild.” Wait, not a “rebuild,” but an “IRAN,” and not the Islamic Republic one. This IRAN means “inspect and repair as necessary.” Why would a relatively low-time engine (500 hours) have an IRAN done on it, your average pilot—which I am—may ask? Turns out if you (me) run it almost out of oil while you’re flying, the inside of the engine gets a little “burned-up.”

Why would a pilot run an engine until it’s out of oil? I would like to think I’m perfectly capable of running an engine dry all by myself, through my very own stupidity. But I had help. The mechanics who did my last oil change thought they’d add a “quick drain” sump plug to my engine. That way, in the future, a mechanic could just put a hose on the protruding metal tube, push and turn, and the old oil would flow out. Note: “protruding” is a key word here.

The little inch-and-a-half long metal tube that hangs down from the sump plug was pushed up by the nose gear assembly every time I raised the nose gear. Which turns out to happen after every takeoff. Who knew? Not the mechanics, who didn’t swing the gear to check to see if there was clearance on that plug. This lack of clearance between the nose gear and the drain tube attached to the sump plug caused all sorts of mischief.

BZZZZZZZZ!

So it’s the first flight after the oil change, with the new, convenient quick drain installed. The wind at nearby airports advertised sporty crosswinds, so I decided to just beat up the traffic pattern at my home-base airport, the Leesburg (Va.) Executive Airport (KJYO). So I take off with my new oil, raise the gear, do a pattern, land and full stop, and then taxi back to the runway. I take off again, do another pattern, and this time decide to do a touch-and-go. I take off after the landing, raise the gear, climb out a bit and “BZZZZZZZZ!” The propeller goes into a high-rpm overspeed, like 3500 rpm or so. “Whoa,” and might I add, “Nelly!”

I pulled the power back some, turning crosswind, and then downwind. BZZZZZZZZ! BZZZZZZZZ! Two surges of the propeller, uncommanded by me—I didn’t touch anything, not the throttle nor the propeller control. Then I looked down and my heart froze—I had nine psi of oil pressure! I was on downwind, in a twin-turbo 350-hp, four-seat aircraft, at 800 feet agl, because of the wretched local pattern altitude. With almost no oil pressure on the gauge.

The tower clears me to land while on downwind. I don’t declare an emergency—I’m waiting for the engine to seize. I’m thinking, “Stay calm, just get it on the ground, get it on the ground, get it on the ground.” I put the gear down, get three green lights—yes!—start the flaps tracking down and turn base leg. A short, angling base leg, as one does with nine psi on the oil gauge.

I look at the runway, look at the airspeed indicator and realize I’ve got the runway made, even if the engine seizes up. “Go ahead, throw a rod through the cowling. Do it. Blow up, seize—I don’t care.” I relax just a bit and land uneventfully. I taxi off the runway, and see that I now have—wait for it—10 psi of oil pressure, which I thought was weird. So I taxied to the shop that had worked on it, not knowing what the problem was.

It turned out that in three takeoffs, a full-stop landing, a touch-and-go and the last full-stop landing, I managed to drain eight of the 10 quarts of oil on board. It was the quick-drain, quickly draining oil out every time the gear was raised. Ten minutes or less of flying.

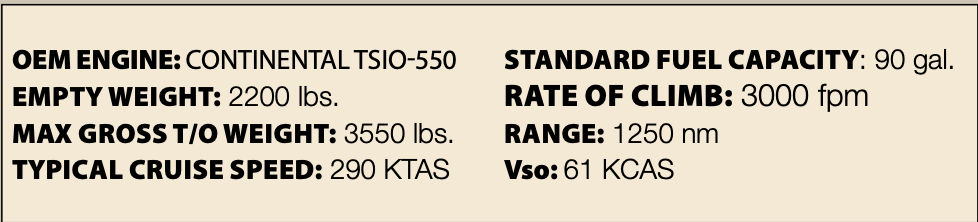

The Lancair IV-P is a single-engine, pressurized, four-seat retractable certificated in the Experimental category. As a home/kit-built airplane, the specifications below may vary from airframe to airframe.

According to sister publication Kitplanes, some 360 examples were constructed. Lancair, the kit manufacturer, sold off the IV-P and its other designs in 2017 and later became the Evolution Aircraft Company. The Lancair line of airplanes was acquired by Lancair International.

BACK TO THE SHOP

So the propeller, prop governor and alternator had to be overhauled, and the entire engine sent off to an engine shop. I got a call one day to go look at my disassembled engine at the shop. The parts were all laid out in an orderly fashion, perhaps like you’d lay it all out for an eighth-grade shop class.

The head mechanic explained, “See here, this darkened main bearing? Because of this one bearing, the crankshaft will have to be overhauled, and all new bearings put in,” and on and on. He said, “If you had flown that aircraft 10 more minutes, the engine would have come apart. Engines come apart in different ways—they come apart the way they want to,” and then listed off a few ways. Like rods coming out the top of the cowling. I remembered that one.

It took them several hundred hours of labor and about two months to IRAN that engine. Then one fine day it was “done,” and they brought it back from the nearby engine shop, and the local guys installed it in my aircraft.

I took off and orbited, making about 30 circles overhead, in case something went wrong. Feeling somewhat confident, I even tentatively ventured over to a nearby airport, and then back home. All went well with this flight: No leaks, engine ran fine. I flew the next day, and the next, and the next, wanting to do two things—get back in the air and get proficient after three months off, and to break in the engine.

After flying about 25 hours, I took the aircraft in for an oil change, which they did (no quick-drain plug this time—I checked). Now the aircraft is ready to fly normally, all broken-in, with new oil.

Anyone who’s changed an engine’s crankcase oil—on any engine—knows the task can be very messy. In the often-confined area beneath an aircraft engine, it can be difficult/impossible to get a wrench on the sump drain and, even if you can, the results can redefine “messy.” So the quick-drain sump plug was invented, and is used in many applications, not just aviation.

Basically, it’s a sump plug with a spring-loaded valve that’s normally in the

closed position. To open the valve, push up from the bottom, then twist to lock it in the open position and drain the oil. To close the valve afterward, twist in the opposite direction

and the valve snaps down to its closed position. Easy peasy.

Importantly, the valve doesn’t have to be twisted to remain open. All it takes is enough constant pressure from below to open the valve. Like when a nose landing gear is retracted, and the tire or part of the assembly pushes up on the quick drain from the bottom.

Quick drains typically are not a troublesome weak spot. I have one on my Debonair, but there’s also a bulkhead below it, which keeps the quick drain’s valve separated from the nose

landing gear. —J.B.

BACK IN SERVICE

I fly a short flight, maybe 0.3 of an hour in the pattern, and park it. When I returned two days later to fly a four-hour cross-country, I noticed a few drops of oil on the nose gear. I looked up at the oil drain plug, saw a drop hanging from it and reported it to the mechanic. This was a Sunday. He texted me, “What do you want to do, park it at our shop and we can look at it on Monday? It probably needs a new crush washer.” I said no, I wanna fly to Missouri; a few drops of oil isn’t bad.

Turns out the oil drops were a harbinger of bad stuff. A harbinger. Many cultures, I read, consider the rooster to be a harbinger of good luck and good fortune. I wonder what those cultures think about a “rooster tail” of oil spewing out of the engine. But I’m getting ahead of myself, foreshadowing even.

No one was more surprised than I at what happened next. I was flying along eastbound at 11,500 feet, fat, dumb and happy, and—whoa! The engine very suddenly started making a strange noise and running rough, the aircraft vibrating a bit. Suddenly my heart is in high gear and running rough, too. Funny how that happens.

DIVERTING

I immediately pushed in the mixture control all the way, which is what the checklist says to do, among other things. No change. I looked—good oil pressure, oil temperature and…the #1 cylinder has no EGT, no CHT. Shoot! I’m running on five of six cylinders. No wonder it’s rough.

I look at my really nice Garmin G3X screen, and see the nearest airport is like 4.5 miles away. But is the runway long enough and are the winds okay? Yes and yes.

Now, I’m right over the airport—Crawford County Airport, KRSV, near Robinson, Illinois. I spiraled down, putting out the speed brakes, throttling back to idle, dropping the gear and, on final, flying along in a near-idle power setting, because I was still high and fast, trying to lose altitude. Oops, then I realized I was a little low and needed to add power. My heart froze—what if there was no power? What if the engine was dead?

It wasn’t, and responded to throttle input. I landed with a 10-knot crosswind and taxied in. Before shutting down, I called the Leesburg mechanic, who said to run it up to 1800 rpm and check the mags. I did; both were okay, but the #1 cylinder was still dead, so I shut down.

TELLTALE TRAIL

I got out, and there was a big oil trail to my parking spot—an oil slick, really—oil underneath in a puddle and oil all down the right underside of my airplane. Whoa.

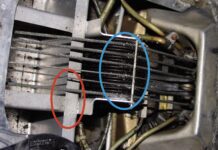

A local mechanic pulled it into his shop and the next morning, when he had time (he had to finish up a Bonanza and couldn’t look at mine immediately, he said), pulled off the top cowling. Well, well, lookie here—two holes in the #1 cylinder’s rocker arm cover. Two holes spewing oil.

The rocker arm cover is bolted to the #1 cylinder, which is brand new, 30 hours old. Oh, did I mention that I bought six new cylinders for $15,000 when the engine was IRAN’d? I did not. When they tore my engine down, there was rust pitting in all the cylinders from the previous owner letting it sit a long time in a hangar without flying. A low-time engine that has been sitting for years is not a “good” low-time engine, I found out. Water accumulates in the cylinders, and rust forms. So I got new ones, since they were tearing down the engine anyway.

This new rocker arm had two holes, one bigger than the other. Two bolts hold the cover on, with locking flanges. One bolt was broken clean off, the other loose. The mechanic showed me how the locking flanges were not bent up like they were supposed to be. They’re like safety wire, or a cotter pin—they keep the bolts from loosening. Mechanic error.

AFTERMATH

So I got a ride to Indianapolis and airlined to Dulles, an hour and eight-minute flight, and then took a $69 Uber ride 10 miles home.

The local shop that rebuilt the engine sent out a mechanic, and he replaced the rocker arm cover and pushrod, plus some other parts, and checked all the rocker arm covers and then signed it off. Then I flew it home VFR with flight following, dodging massive thunderstorms all the way.

But who cares about deviating for weather when you have full tanks and a good engine? Thunderstorms are spectacular, aren’t they, if you’re not in them? Massive dark or whitish rain shafts, spewing straight down out of low clouds, hitting the ground and bending outward, like a microburst. Black, white and blue clouds, with lightning, blue sky in between. It was good to be flying again.

LESSONS FOR ME

In the future, if there is oil leaking, I’m going to find that leak before flying. When flying, I always keep track of where the nearest airport is with a long enough runway to land on. These practices came in handy this time, as I knew where it was, in general, before the cylinder problem. Mechanical work—things can and do go wrong, so we have to be ready for an engine problem.

I did do a couple of things right. In the pattern back at Leesburg, when the propeller went into overspeed, the oil pressure gauge’s low indication told at least some of the tale, and was all the encouragement I needed to get back on the ground.

At the end of the day, there’s no way a mere pilot can inspect and verify the condition of every component on the aircraft. We have to trust the mechanics who work on what we fly to do their jobs correctly. In my case, two different mechanics made two different mistakes: failing to perform a gear swing to verify that the newly installed quick drain didn’t conflict with the retracted nosegear, and failing to properly secure the rocker arm cover. That’s why we need to keep track of where we and the nearest suitable airport are, and why we need to be proficient at engine-out maneuvers.

Matt Johnson is former U.S. Air Force T-38 instructor pilot and KC-135Q copilot. He’s now a Minnesota-based flight instructor.