About this time each year, this magazine includes some admonishments to those planning to fly to an airshow. They can be as basic as recommending familiarity with an associated Notam or include a detailed analysis of the challenges. In either case, risk-management concepts like checking and understanding weather, and avoiding such human foibles as “get-there-itis,” are incorporated or implied. But not always implemented.

Maybe it’s a Pollyannaish outlook: “I’m flying to an airshow; what could go wrong?” Or maybe the pilot has waited all year for the upcoming trip, planning and visualizing the outcome all the while. Disruptions to that planning, which also may disrupt the anticipated outcome, are to be avoided and, in many cases, simply ignored. That’s just human nature.

Indeed, the pilgrimage to a favorite airshow may be the only long cross-country trip a pilot has flown recently. Parsing the pages of weather reports and forecasts is just like any other skill—it atrophies when not exercised. Of course, for some it won’t matter what the TAFs advertise, since they’re going anyway.

This magazine also has long advocated for any pilot who contemplates using an airplane on a schedule to earn and use the instrument rating. As long as your mission depends on meeting a schedule, no matter how loosely defined, being able to fly it IFR can mean the difference between success and…something else. Too often, however, we see the sad result when the “I’m going anyway; what could go wrong?” attitude confronts the reality of instrument conditions. Here’s an example that combines all these factors, and many more.

BACKGROUND

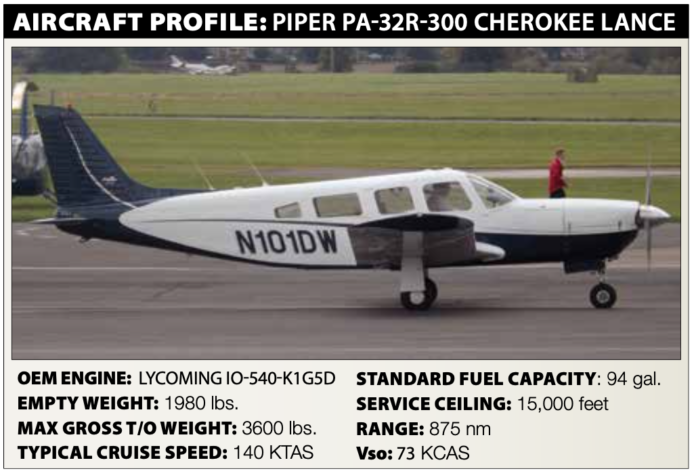

On July 24, 2018, at about 0521 Eastern time, a Piper PA-32R-300 Cherokee Lance was substantially damaged when it impacted terrain shortly after takeoff from the Lincolnton-Lincoln County Regional Airport (IPJ) in Lincolnton, N.C. The non-instrument-rated private pilot/owner (male, 63) and his passenger were fatally injured. Instrument conditions prevailed.

According to a family member, the pilot was off to attend the Experimental Aircraft Association’s AirVenture fly-in, in Oshkosh, Wis. Contemporaneous media coverage of the accident revealed that the airplane had emerged only two weeks earlier from a maintenance shop after landing off-airport in August 2017 due to engine failure.

Data from an Appareo Stratus 2S portable ADS-B In receiver indicated the airplane departed Runway 05 at about 0520. At about 0520:25, the pilot initiated a left turn as it climbed from the runway. The airplane continued the climbing left turn to about 1100 feet GPS altitude and attained a groundspeed of about 95 knots. Then it descended to about 950 feet and accelerated to a groundspeed of about 121 knots on an approximate left downwind leg for the departure runway.

By about 0521:10, the airplane had climbed to 1480 feet GPS altitude and decelerated to about 56 knots groundspeed. The airplane subsequently entered a descending left turn; the final recorded data point captured a GPS altitude of 1050 feet and a rate of descent greater than 4000 fpm. The accident site was in an open field about ½ mile northwest of the airport.

According to FAA Advisory Circular AC 60-22, Aeronautical Decision Making, as quoted by the NTSB, “Pilots, particularly those with considerable experience, as a rule always try to complete a flight as planned, please passengers, meet schedules, and generally demonstrate that they have ‘the right stuff.’” One of the common behavioral traps identified was “Get-there-itis.” The text stated, “Common among pilots, [get-there-itis] clouds the vision and impairs judgment by causing a fixation on the original goal or destination combined with a total disregard for any alternative course of action.”

At right, the accident airplane’s flight track, as determined by a portable GPS device, is overlaid on a Google Earth representation of the departure airport, showing how close the pilot got to his goal of attending EAA’s 2018 AirVenture fly-in.

INVESTIGATION

All major components of the airplane were accounted for at the scene. The wreckage path was about 170 feet long, oriented on a 085-degree magnetic heading. The grass surrounding the wreckage path displayed fuel blight. The wing flaps and landing gear were retracted. Flight control continuity was confirmed from all flight control surfaces to the cockpit.

The fuel injectors, oil pump and oil filter were free of debris, as were the fuel selector valve and gascolator. No damage was noted to the engine-driven fuel pump’s internal valves or diaphragms. The vacuum pump remained attached to the engine and rotated freely by hand; its carbon rotor and vanes were intact.

The propeller was located about 50 feet forward of the main wreckage. All three blades were bent aft and exhibited chordwise scratching and leading edge gouging, consistent with being under power at the time; one blade also exhibited S-bending.

The pilot’s medical certificate carried the notation, “Not valid for any class after June 30, 2018.” The last entry in the pilot’s logbook was on December 1, 2017. As of that date, he had recorded 624.3 total hours of flight experience. He had accumulated 3.3 hours of simulated instrument time as of July 18, 2014.

About 18 hours before the accident, the pilot used ForeFlight to view visibility and precipitation forecasts for the proposed route. A review of aviation weather vendors and third-party users of the Flight Service system revealed the pilot did not obtain an official weather briefing on the day of the accident. At the time of the accident, an Airmet Sierra issued well after the pilot’s ForeFlight session warned of instrument conditions due to precipitation, mist and fog. At 0445, reported weather at IPJ included calm winds, four statute miles of visibility in mist and an overcast at 200 feet agl. The temperature and dew point were the same: 21 degrees C. The accident occurred about 40 minutes before the beginning of civil twilight.

PROBABLE CAUSE

The NTSB determined the probable cause(s) of this accident included: “The noninstrument-rated pilot’s intentional visual flight rules flight into instrument meteorological conditions, which resulted in a loss of control due to spatial disorientation. Contributing [to] the accident was the pilot’s self-induced pressure to complete the flight as planned.”

This accident has all the elements of things pilots are constantly cautioned against. Taking off into IFR without an instrument rating is perhaps the most readily understood, but we also have dark night conditions, a pilot whose last simulated IFR was four years earlier and lack of recent experience with the accident airplane—it had been in the shop for almost a year. Then there’s an expired medical, failure to obtain and understand a pre-flight weather briefing, and lack of recent flight experience—his last logbook entry was seven months earlier. Last but not least is what the NTSB called “self-induced pressure to complete the flight as planned.”

Popular airshows like AirVenture always tempt pilots to cut corners and ignore some options, like leaving the day before, or waiting out weather before taking off. Among the many other factors here, “get-there-itis” is a real thing.