Pilots fly for a variety of reasons. If you’re like me, transportation is the main reason to own an airplane. Flying a single-engine general aviation airplane can be an effective way to travel for business and personal reasons, especially in this era of degrading, inflexible and unpredictable airline service. However, to safely use small aircraft for this purpose and manage the risks, you need to expand the scope of your typical planning efforts and be ready to change schedules and even cancel some portions of a trip. This is especially true if, like me, your travel requirements include the entire United States.

I’ve written about using small aircraft for transportation before in this journal (for example, see “Flying for Transportation,” March 2013). However, the best way to illustrate this process is to describe a typical multi-stop “mission” that I typically accomplish two to four times a year.

The Mission

I have clients and other business commitments all over the United States, and occasionally in Europe. This is the main activity for which I use my current airplane, a 1990 Mooney MSE (M20J). I don’t use the Mooney to travel to Europe, in case you were wondering. Some of these commitments involve speaking engagements or other events with a fixed timetable, while others are appointments which can be changed by me or the client.

I typically try to bunch commitments together and schedule them so that I can effectively complete an itinerary without wasted travel. For example, if I chose to schedule events randomly and individually, I would often be wasting a day each way on travel for a single-day meeting. On the other hand, with the Mooney, I can travel three or so hours in the morning for an afternoon meeting 400-500 nm away and then repeat the process each day, thereby rarely losing a full day for travel.

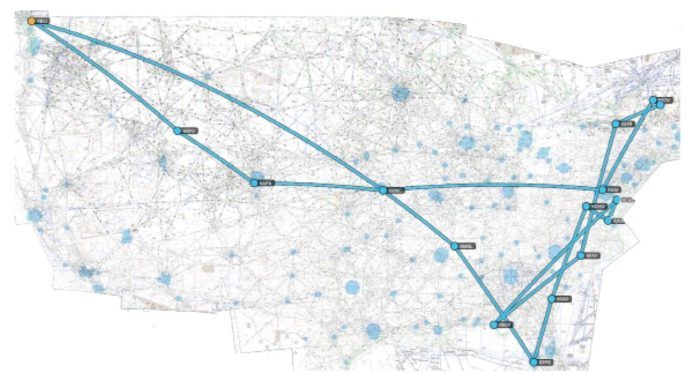

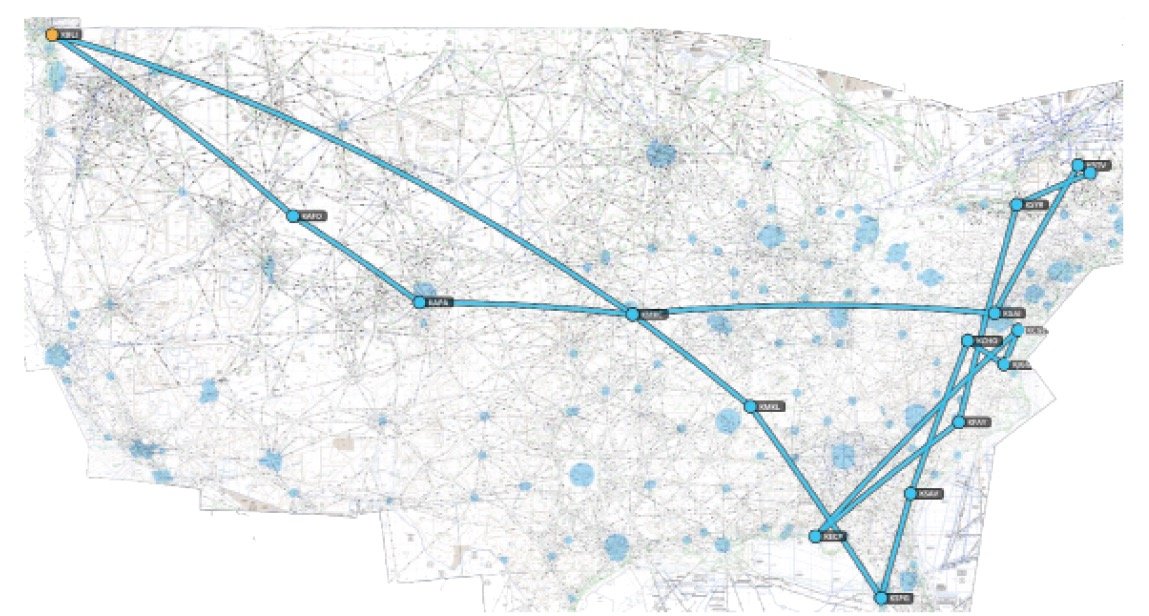

The trip I’ll use to illustrate this process took place in late 2018—from September 12 to October 22. I flew 62.1 hours from my home in Bellingham, Wash., to points as far northeast as Vermont and as far southeast as Florida. As originally scheduled, the trip included 22 separate meetings or events at 18 different stops. Not all the stops involved business—I also had several weekend layovers with friends.

There are several upfront considerations to address when attempting to use small airplanes to accomplish a trip of this nature. The sidebar above is a summary. I’ll address the tactical risk considerations of this trip using the acronym PAVE, which we know stands for Pilot, Aircraft, enVironment and External pressures.

The Pilot

When starting a long trip such as this, I am often the main obstacle to minimizing risk, if I haven’t paid due attention to qualification, proficiency and aeromedical issues. Minimizing these risks starts days or weeks before a planned trip, and this trip was no exception.

I try to maintain proficiency between trips, and this is particularly true for high-workload tasks such as flying in instrument conditions in busy airspace. During the winter months, when I travel very little, it is easy to find instrument conditions in the Puget Sound area, and I try to maintain proficiency within the busy Seattle terminal airspace. In the four weeks prior to this trip, I made some flights in the Northwest with plenty of exposure to instrument conditions and high workload, so I felt proficient.

Aeromedical factors are just as important, and I use the IMSAFE acronym to catalogue these (that’s Illness, Medication, Stress, Alcohol, Fatigue and Emotion). Some came into play on this series of flights, and I took positive steps to mitigate their risks. The three IMSAFE factors of most concern were stress, alcohol and fatigue. I find the key to reduced stress is to create a schedule that allows for some down time and doesn’t pack meetings too tightly together. I go easy on the alcohol the night before a flight on these multi-stop trips. I try to minimize fatigue by getting to bed earlier than I would at home. The biggest fatigue driver is spending three or four hours at 10,000 or 11,000 feet. I try to minimize this by liberal use of portable oxygen. Generally, if I’m at 11,000 feet eastbound on a three-hour mission, I’ll use oxygen on the last hour of the flight if conditions are benign. I measure my blood’s oxygen saturation with a pulse oximeter—if the device shows a value below 92 percent, I use oxygen continuously.

The Airplane

Your choice of airplanes is important if you want to travel. My Mooney is almost the perfect airplane for my missions. It has nearly seven hours of endurance, which translates to healthy reserves on my typical three-to-four-hour legs. It’s not a particularly good choice to take off pavement, but these days most of my flights are to places with Marriott room service and not the Idaho outback.

The Mooney does come with some limitations, as do all personal airplanes. The most prominent one is that it is not approved for flight in known icing. This was almost a factor on the mission and could have hastened my departure from the Northwest for points east. However, as my planned departure day approached, I realized that icing wouldn’t be a factor. On the other hand, moderate turbulence was forecast. I was able to top it at 15,000 feet and strapped on the oxygen for the flight to Afton, Wyo. I needed to cruise at that altitude again for the next leg to Englewood, Colo.

I follow a rigid program of preventive maintenance with my airplanes to increase reliability, and this has resulted in great dispatch reliability. On this trip, however, I had two outages, one of which disrupted my schedule. The starter gave up the ghost in North Carolina, but I was able to get back in the air after only a one-day delay. Later, in Florida, the battery died after I accidentally left the baggage compartment light switched on. Fortunately, I had hired someone to change the engine oil, and they discovered the problem and corrected it before I had to depart at my scheduled time.

The Environment

On most flights of this nature, environmental hazards and associated risks will be the greatest risk-management challenge. You will encounter multiple weather systems and face changing terrain, multiple airports and airspace, and other hazards. This series of flights proved to be no exception, with two hurricanes (Florence and Michael) and other issues as part of the challenge.

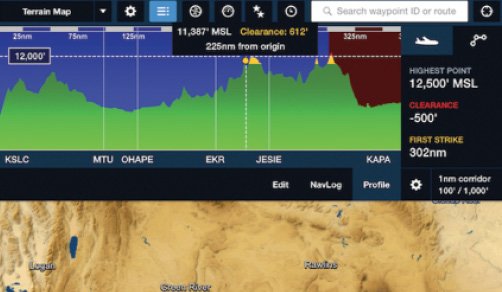

I earlier described my two flights from Bellingham to Afton, Wyo., and then to Englewood, Colo. I flew high on these legs to avoid turbulence. My only other concern was a high-density altitude departure from the 6200-foot-high runway at Afton. I mitigated the small amount of risk there by making an early morning departure when temperatures were cooler. Having previously owned another Mooney of this model, I’ve found that they perform well during such departures, with their high-aspect-ratio wings—better, in fact, than the two Bonanzas I owned with 85 more horsepower.

After departing Englewood for my next meeting in Kansas City, I began to monitor Hurricane Florence as it moved in from the Atlantic toward the Carolinas. Departing from Kansas City for Washington, D.C., I warily watched Florence’s track. However, my own track was well north, and I encountered nothing more than light headwinds as I flew on the north side of the deep low toward my next set of meetings in Washington. Fortunately, a business colleague in D.C. offered me the use of his hangar in Gaithersburg, Md., since his Mooney was away for modifications. While I spent four days of meetings in D.C., the remnants of Florence passed by.

From there, I departed for Burlington and Montpelier, Vt. for business meetings and a weekend layover to enjoy my friend’s wine cellar. I then headed west for a meeting in upstate New York, followed by a flight to Panama City, Fla., for a Mooney safety event. It was in Fayetteville, N.C., my refueling stop, that the starter failed. I had added a day to ensure that I would arrive in Panama City in time for my speaking engagement so the loss of a day wasn’t disruptive. It also furthered my emerging opinion that I should normally stick to airports that have maintenance services for my fuel stops if I don’t want to risk logistical problems and schedule disruptions.

I departed Panama City for Cambridge, Md., for a day-long layover with friends and then to Williamsburg and Norfolk, Va., for business meetings. I then headed to Charlottesville, Va., for a weekend layover.

The weather then again became sporting as Hurricane Michael headed for the Florida panhandle, complicating my next leg to Knoxville, Tenn. The weather there was getting dicey as Michael approached, so I cancelled the Knoxville meeting and headed to Savannah, Ga., rather than get marooned in Knoxville. This time, I spent a lot of time deviating around convective activity on the far east side of Michael and fighting headwinds from the deep low. At least Savannah was on the far side of Michael’s northerly track. I departed Savannah for St. Petersburg, Fla., and by chance was able to fly in a large clear area between two heavy bands of convective activity off the east coast of Florida and over the Gulf of Mexico. I then hangared the Mooney and spent another 10 days in St. Petersburg and Orlando.

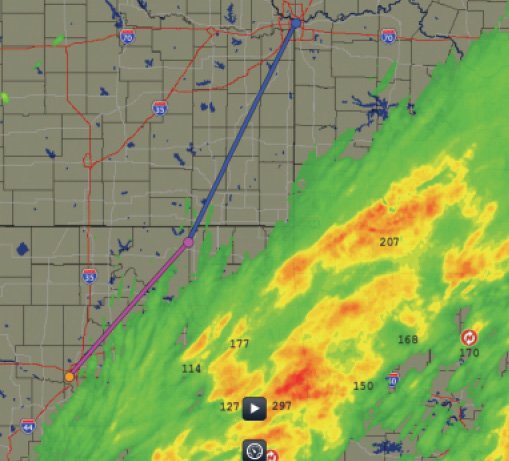

So far, my itinerary had mostly been a success with only one cancellation. However, as I watched the long-range weather forecast, I could see trouble brewing in the North Pacific and eventually decided to cancel my meetings in Kerrville, Texas, and Albuquerque, N.M. I thus headed directly back toward the Pacific Northwest. There was a weather system between St. Petersburg and my RON stop in Kansas City, so I paid close attention to the convective forecast. They were not predicting any convective activity between my refueling stop in Jackson, Tenn., and Kansas City, and all the other indicators predicted a stable air mass with moderate precipitation. The image on the opposite page shows the ADS-B Nexrad depiction of that storm system.

Using a small single-engine piston for nationwide travel may not be for everyone. Even though this is a safety journal, I’ll address the cost issue up front. If your typical travel is from New York to Los Angeles and back after a single meeting, the airlines will not only beat you there by days, they will also cost a tiny fraction of what flying yourself would. On the other hand, if you are making 18 stops in places like Afton, Wyo., and there are two of you traveling, you may find using a personal airplane can save you time and money.

I also don’t believe that most newly minted 60-hour private pilots, or for that matter 150-hour pilots with a new instrument rating, should consider using an airplane for nationwide travel on a schedule. It’s not the lack of experience that increases the risk—it’s that most pilots today have not been properly taught practical risk management. This is starting to change and, perhaps 10 years from now, most pilots will have these skills. If, on the other hand, you have mastered the risk management process, then more options might be open for less-experienced pilots to range far and wide.

The airplane you select for such travel is also important. When flying the Lower 48, speed matters. I would consider something that travels at least 150 knots with a five-hour range to be the minimum needed to make this enterprise both practical and effective in minimizing risk. Of course, turbocharging, known-icing approval, a second engine, pressurization and turbine power confer additional practical benefits along with different risk management challenges.

A working autopilot is essential to minimizing risk when using a high-performance airplane for this kind of travel and, whether panel-mounted or portable, some form of moving map with long-range data link weather is also a key piece of equipment for minimizing risk.

Consider these basic guidelines when contemplating a multi-day trek in a personal airplane:

What’s Your Mission?

You can surmise from my account of this trip that my strategy for mitigating external pressure hazards and risks is based on building extra time into the schedule, canceling stops if required by conditions and looking ahead for potential hazards. I still completed 19 of my 22 planned events, including four with fixed dates. My experience on this trip is similar to most of my previous trips. Your missions may not be quite as extensive as mine, but you can use a high-performance general aviation airplane for reliable travel if you follow some basic guidelines like those listed above.

Nationwide Roaming Guidelines

Upfront risk management and other considerations

Robert Wright is a former FAA executive and President of Wright Aviation Solutions LLC. He is also a 9900-hour ATP with four jet type ratings and he holds a Flight Instructor Certificate. His opinions in this article do not necessarily represent those of clients or other organizations that he represents.