Like thousands of my closest friends, I made the pilgrimage to Oshkosh, Wis., in late July for the Experimental Aircraft Association’s annual AirVenture Fly-In and Convention. As has been the case with the show in recent years, the 2018 edition set another new record for attendance, with some 601,000 people moving through the gates. At Oshkosh’s Wittman Field, there were 19,588 aircraft operations during the 11-day period from July 20-30, according to EAA, an average of approximately 134 takeoffs/landings per hour. I contributed two of those operations.

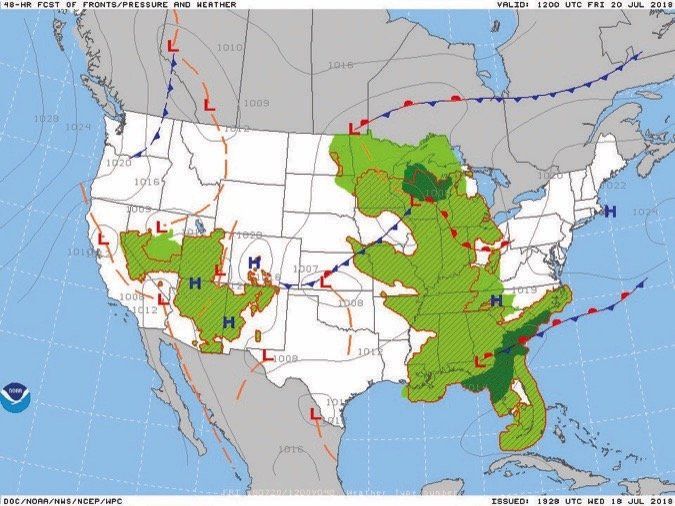

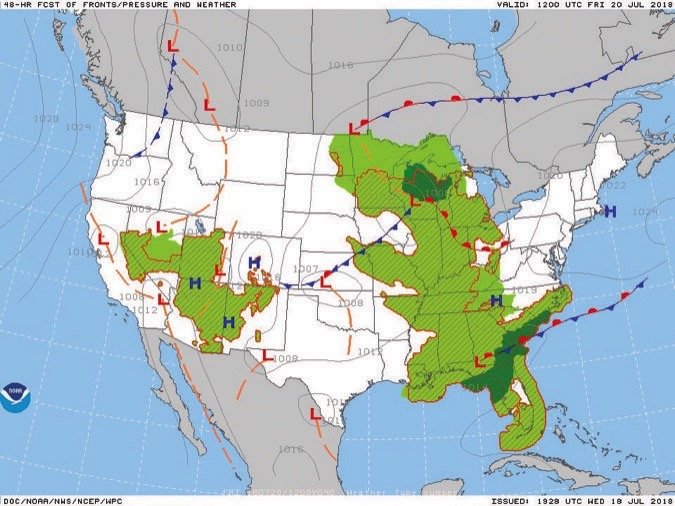

Whoever coined the phrase “getting there is half the fun” may have had general aviation and personal airplanes in mind. But not all of my journey was fun, depending on your definition. My trip started in earnest two days before my planned departure, with a check of the 48-hour prognostic chart, reproduced below. It advertised typical summer thunderstorms along much of my route, especially in Florida, with a promise of a low-pressure system hovering over southern Wisconsin and central Michigan. My initial plan included trying to use that low to grab a tailwind into OSH from northern Indiana after a fuel stop in Kentucky. My plan almost worked.

Getting out of Florida was the first challenge, and took almost two hours, thanks to deviations for weather. Although I had filed for 10,000 feet as a cruising altitude, soon after takeoff I decided that staying low was a better plan, thanks to improved visibility between thunderstorm bases and rainshafts. My eventual route north included three substantial deviations for weather, including one that required a 90-degree turn. Once I got around the lines of storms streaming in from the Gulf of Mexico, I had a relatively clean and open shot at my initial destination, Cheap Fuel Muni, Kentucky, to top off the tanks.

From a couple hundred miles out, I watched ADS-B In’s Nexrad paint some extreme weather just north of my planned fuel stop. It stayed just north of that field throughout the cruise phase and my approach. Winds were pretty close to my personal limits, with a 15-knot direct crosswind, gusting to at least 20, but I got down in one piece and taxied to the self-serve pumps.

All topped off and pushed back out of the way, I popped inside the FBO to use the facilities and grab something to drink. About the time I came back outside to preflight and file my next flight plan, the weather that had been staying north of the field was getting a lot closer. Then all the cellphones in the FBO went off, with an alert announcing a tornado warning. So much for a quick turn. In moderate rain and gusts, I secured the airplane as best I could and scrambled back into the FBO, drenched. Ahh, the joys of personal aviation.

While waiting for this storm to blow through and my clothes to dry out, I looked at the weather along my planned route: due north to Muskegon, Mich., then across Lake Michigan to OSH. The tailwind definitely was still there, but the low I wanted to take advantage of for my last leg was spawning lots of yellow, red and other colors north of Chicago and across the Lake. It was pretty marginal before I factored in the expanse of water and the lack of suitable bolt holes.

Plus, I prefer to be high—at least 8000 feet msl—when crossing Lake Michigan in a single, for obvious reasons. Crossing from Muskegon directly toward OSH at that altitude or higher means only a few-minute-long stretch when I’d be out of gliding range from land if something happened. But the weather was telling me I couldn’t be assured of a direct route, lengthening my exposure.

There was little choice: I filed IFR along a published route that would take me west of Chicago and north over Rockford, Ill., and Madison, Wis., then a jog to the northeast toward OSH. By this time, the tornado-warning storm had blown through—barely—and I was looking at blue skies in my direction of travel. To give you an idea of the kind of weather that had blown through, the windsock had switched and was now favoring a takeoff opposite the way I had arrived. The departure was bumpy, but I was soon motoring off toward the first fix on my clearance.

Now, the clock became a factor. Owing to a late start earlier in the day, all the deviations and the stiff headwind I was flying into, all the gadgets were telling me I’d be over OSH at about 2015 local time. That was just spiffy, since the field closes at 2000 local. I was pretty much running flat out and going through lots of freshly purchased 100LL, but my ETA wasn’t changing much. At one point, I had a groundspeed below 100 knots, despite truing out at around 165.

I didn’t make it to OSH that evening. By the time I was within range and despite pushing the power controls all the way forward, the best ETA at OSH I could muster showed 2002, which wasn’t going to cut it. I ended up shooting an RNAV approach into Madison and calling it a (long) day.

The next morning, I was able to slip out of Madison under some low ceilings and get to OSH in decent VFR. Many others weren’t so lucky, including the mass arrivals scheduled for that day. The ForeFlight screenshot above shows a snapshot of Sunday’s arrival traffic.

Despite incurring an unplanned overnight stay and the consequent delays, it was a couple of good days in the airplane. I covered some 1100 nm, logging some actual and two approaches. The trip home was even better, something I managed to complete in the same day, landing at home plate right at dusk. It was another good day in the airplane.