Owning an aircraft is an empowering experience. Winged assets in your hip pocket can open up all kinds of opportunities and adventures free of many concerns associated with traditional clubs and aircraft rental operations. It’s also an awesome responsibility, often isn’t kind to your wallet and can bring many new and unanticipated challenges.

For one obvious example, owners become responsible for ensuring that all maintenance and inspection requirements are met and the aircraft is airworthy. While it often can be tempting to postpone or refuse to buy expensive parts and services, it’s a “pay me now or pay me later” situation where deferring inspections or repairs may seem economical at first blush, such actions have a way of catching up to us in the end. Then there’s the ethical issue of carrying innocent passengers who place their faith and trust in the owner/pilot that the aircraft is safe and airworthy, and meets current, accepted standards.

As both the pilot and aircraft age, it’s easy for complacency to creep in, manifesting itself in dangerous ways. We might cut corners on basic training or responsibilities other pilots readily accept, for example, or place more faith in our experience with the aircraft than is warranted. Just as we should ride with an instructor more often than every two years to establish and retain proficiency, we also should be getting an unbiased, professional (read “expensive”) mechanical assessment of the aircraft from time to time.

Failing to embrace these responsibilities can lead to all sorts of mayhem, ranging from simple paperwork issues to the catastrophic. Here’s an example of how a complacent owner can lead to the latter.

BACKGROUND

On January 6, 2020, at 1423 Eastern time, a 1966 Cessna 172H Skyhawk was destroyed when it collided with terrain while maneuvering near Newborn, Georgia. The solo private pilot (male, 72) was fatally injured. Visual conditions prevailed.

The owner/pilot departed Toccoa, Georgia, at about 1230, destined for Cairo, Georgia, some 240 nm away. The pilot’s daughter later stated he likely wanted to look at property in the Cairo area. The pilot’s daughter was not aware of a reason the pilot would be looking at property near the accident site. Newborn is approximately 70 nm from Toccoa.

According to FAA data, about an hour into the flight, the airplane began flying “a meandering track” for about 10 miles, and then made a right turn to the north and completed several left 360-degree turns before completing two additional right 360-degree turns. After briefly turning north, it completed several more 360-degree turns before continuing into 13 360-degree right turns progressing in an easterly direction until radar contact was lost near the accident site.

Two witnesses observed the airplane flying low just before the accident, and another witness stated that the airplane was circling and then descended below the tree line. The airplane impacted terrain and a post-accident fire ensued.

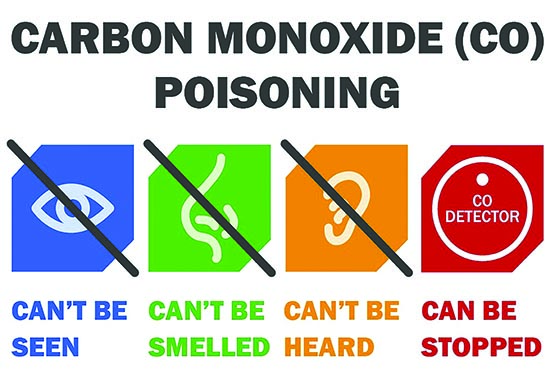

We’ve run a number of articles over the years about carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning aboard personal airplanes. The basics remain the same: good maintenance of the exhaust and ventilation systems, some kind of modern detector and awareness of related symptoms, capped off by deciding that there’s a problem and doing something about it. Early CO-poisoning signs can be mistaken for everyday symptoms of something else. So it’s important to know that the combination of these conditions should be a flashing red light. According to the Mayo Clinic, those symptoms include: • Dull headache • Weakness • Dizziness • Nausea or vomiting • Shortness of breath • Confusion • Blurred vision • Loss of consciousness

INVESTIGATION

The airplane impacted dense woods and terrain on a magnetic heading of about 215 degrees and left a debris path about 180 feet long, coming to rest inverted. Both wings had separated and the fuselage was consumed by a post-impact fire. All major components were located at the scene and in the debris path.

The left and right flaps were found in the retracted position. The propeller was sheared off the engine; it displayed gradual aft bending and diagonal chordwise scrapes on the blades. Flight control continuity was confirmed through multiple overload breaks and failures.

The left muffler was sound with no evidence of cracks or through-thickness metal wastage. The right muffler and shroud were substantially damaged and exhibited cracks and through-thickness metal wastage. Holes and wall thickness loss were also noted around the muffler body. Other than the condition of the right muffler, examination of the airframe and engine revealed no pre-impact anomalies that would have precluded normal operation.

The pilot reported 344 hours total flight time for his most recent aviation medical exam on November 15, 2013. The pilot’s last logbook entry was on July 16, 2019; his total flight time was 358.65, of which 15 minutes were flown during the previous six months.

The airplane’s most recent annual inspection was completed on September 17, 2018. Only three other records of maintenance were found for the 10 years before the accident: two annual inspections on May 27, 2013, and November 18, 2010, and replacement of the left muffler on April 1, 2010. The airplane had been operated about 93 hours over that period.

The mechanic who conducted the 2013 annual inspection and almost all of the airplane’s maintenance from 2008 to 2013 knew the airplane well and was a friend of the pilot. He considered the airplane in “rough shape.” Within the last few years, the mechanic told the pilot he didn’t want to “touch” the airplane unless he agreed to a comprehensive annual inspection.

PROBABLE CAUSE

The NTSB determined the probable cause(s) of this accident to include: “The pilot’s impairment/incapacitation from carbon monoxide poisoning due to a degraded muffler. Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s failure to properly maintain the airplane.”

According to the NTSB, the right muffler’s condition likely led to an escape of exhaust gases and allowed carbon monoxide (CO) to enter the cabin during the flight. Toxicology testing performed identified 48 to 61 percent carboxyhemoglobin in the pilot’s blood. Levels of CO of 40 percent and above lead to confusion, seizures, loss of consciousness and death.

Although toxicological testing detected potentially impairing medications, it is most likely the pilot experienced CO poisoning during the flight, leading to his impairment/incapacitation, as demonstrated in the airplane’s erratic flightpath. The pilot’s underlying cardiac disease would have increased his susceptibility to CO poisoning. The NTSB said, “Had the pilot had the airplane inspected, it is possible that the deteriorated condition of the right muffler might have been detected and corrected.”