One of general aviation’s most time-honored practices involves two or more pilots being aboard the same airplane at the same time. The purposes vary—from training and proficiency, to boring holes in the sky, to chasing down a $100 hamburger, and everything in between—but it’s not at all rare to find more than one pilot seated where they have flight controls in front of them. Most of the time, that’s a good thing: There are two sets of eyes, hands and feet, and if the pilot flying needs a break, there’s someone to keep the shiny side up. It can be a bad thing, though, if both pilots don’t have a full understanding of each other’s duties and responsibilities. When that happens, things can be forgotten or overlooked.

Problems arise when both pilots are trying to fly the same airplane at the same time. The result often can be no one is flying. That’s when hijinks ensue and both pilots become passengers. While the FARs make it clear there can be only one pilot in command, the reality is we often split duties while airborne with two. It usually works out, but clear delineation of responsibilities is a must.

The Crew Model

Commercial and military aviation ran up against the two-pilot problem decades ago. Early airplanes often required only one pilot, but when manufacturers started building airplanes needing more people to fly them, the concept of one and only one pilot being in command began to take on greater implications. The captain or aircraft commander often was all-knowing and his (it was always a “he”…) word was the law. If they ever wanted to move up the ladder to command their own airplane, co-pilots often had to learn to keep their hands in their laps and their mouth shut, speaking or acting only when told. A lot of accidents happened because the right-seaters feared speaking up more than they did running the airplane into something.

Over the years, the aircraft became even more complex, along with the airspace, and the industry eventually came around to the concept that the people sitting up front should be consider a crew, not individuals. One result was eventual development of the pilot flying (PF)/pilot not flying (PNF) concept. At its most basic, this practice dictates that one and only one pilot manipulates the flight controls while the other monitors him or her, reads the checklists, communicates with company and ATC, and performs non-flight-critical tasks like paperwork or tending to passengers. Emergencies are a team effort, but even then one pilot flies the airplane while the other runs checklists and comes up with options.

An corollary of PF/PNF practices is cockpit (or crew) resource management (CRM), which was broadly defined by former National Transportation Safety Board member John K. Lauber as “using all available resources—information, equipment and people—to achieve safe and efficient flight operations.” Basically, CRM embodies two concepts: the aircraft always is under positive control, with no exceptions, and tasks not related to controlling the aircraft are delegated. Today, the CRM concept along with PF/PNF and techniques to implement both practices are standardized across the commercial aviation industry and are a major factor helping U.S. airlines get to the point where there has not been a passenger fatality aboard a U.S.-registered Part 121 operation since 2009.

But full implementation of CRM usually is something beyond the resources of the typical general aviation pilot. It’s also not necessary for conducting safe, risk-minimized flight operations. That said, implementing the fundamental premise of CRM—that one pilot flies while the other does something else—is simple. Think of it as a division of tasks.

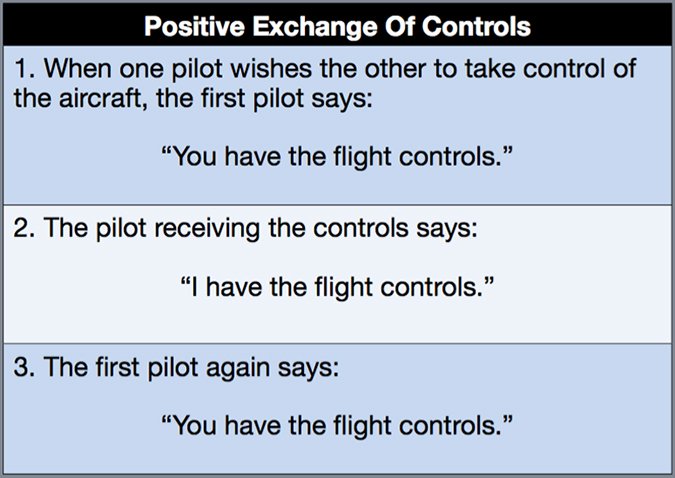

Positive Exchange of controls

When we exchange control of the aircraft—especially in a training environment but, really, at any time—we can’t do it without some formal verification by the pilots that only one of them is controlling the aircraft and they both know who that is. To ensure pilots are aware of this necessity and provide guidance on how the FAA expects it to be done (especially during checkrides), the agency developed Advisory Circular AC 61-115, Positive Exchange Of Flight Controls Program, in 1995. The AC “provides guidance for all pilots, especially student pilots, flight instructors, and pilot examiners, on the recommended procedure to use for the positive exchange of flight controls between pilots when operating an aircraft.”

Sharing Duties…

One of the primary goals of CRM and the PF/PNF concept is sharing of duties. On a jet transport’s flight deck, there are many more tasks to perform than when the same two people are aboard a Cessna 172 heading off for a $100 hamburger. Regardless of whether they’re aboard an Airbus or a Cessna, one thing is certain: Any time the PF is doing anything other than flying the aircraft, no one is flying the aircraft.

Checklists are an obvious and important example. When we fly alone or with non-pilot passengers, we’re left to perform checklists by ourselves. Often, distractions can cause us to lose our place. With two pilots (or even a well-briefed non-pilot passenger) a more-effective challenge/response system can be employed. In this system, one person identifies the checklist task to be performed—engage the engine starter—and the other person performs the task. Both observe the results and agree on the outcome before proceeding to the next checklist item.

The PF obviously is the one manipulating the controls. He or she controls the aircraft’s trajectory and—unless he requests the PNF to perform a task—does it himself. The PNF, meanwhile is performing his or her duties, even it’s only looking out the window for traffic. Ideally, the PNF has other things to do. Examples can include checking weather, working with ATC, navigating, getting the arrival airport’s ATIS and monitoring any gauges he or she can see. Unless the PF requests assistance, he or she keeps hands and feet away from both primary and secondary controls and performs the tasks previously assigned.

At the end of the day, the PNF’s role is to monitor the PF, not just to ensure the PF is fulfilling his or her end of the bargain but also how well the PF is performing. Is he or she maintaining the appropriate and agreed-upon aircraft trajectory? Are desired tolerances—50 feet of altitude and five degrees of heading, for example—being maintained? If not, the PNF should take the agreed-upon steps to bring the deviations to the PF’s attention. Ideally, a discussion will ensue and both persons will agree on a solution.

…But Not Responsibilities

Earlier, we went over the need for one and only one person to serve as pilot in command. Aside from the obvious legal confusion failing to designate a PIC can cause, someone has to be the final authority. In most cases, the cockpit of an aircraft is a poor place to practice democracy. There’s also the matter of logging the flight time.

Perhaps the best example of the two pilots aboard a personal airplane having separate responsibilities arises when the PF is simulating instrument flight with a view-limiting device and the other is acting as safety pilot. The PF may or may not be competent at flying solely by reference to instruments, and it’s up to the PNF to ensure the aircraft is flown safely.

Primarily, this means scanning for traffic and advising the PF if any maneuvers are necessary. In the meantime, however, the PNF needs to monitor the PF to ensure he or she is complying with any ATC clearances, real or simulated, and doesn’t make some of the simple but potentially catastrophic mistakes possible when, for example, practicing approaches. Like descending below DH/DA/MDA without the runway environment in sight or mistaking an intermediate fix for the final approach fix and beginning a descent early.

It’s also important that the PNF keep an eye on the weather and advise the pilot if the flight potentially violates the VFR distance-from-clouds rules. Resolving any such potential should have been part of a pre-flight briefing and handled according to plan.

Finally, both pilots have a responsibility to observe and critique the other in a post-flight briefing on the ground. Such post-flight briefings often are conducted near an adult beverage, and is one of the highlights of two pilots flying aboard the same personal airplane.

Putting It All Together

In any situation involving two pilots in a cockpit, it always should be obvious who is flying the aircraft and who isn’t. How that goal is developed, realized and maintained is up to the two pilots, but above all requires communication, respect and trust. If the two pilots don’t share those traits with each other, perhaps they shouldn’t be out flying around together.

A lot of the foregoing may seem like overkill. A lot of it may well be unnecessary if both pilots are disciplined and understand the potential consequences of failure. If, however, one or both pilots lack experience or have never flown together before, these recommendations may not be enough. In this case, a more formal consideration of CRM concepts may be necessary. Someone has to make that determination before turning the key.

It is said that the most dangerous things in personal aviation are sky above you, runway behind you and fuel in the truck. To which I always add “two pilots trying to fly the same airplane at the same time.”

Sterile Cockpit?

Another factor that arises when two or more pilots are aboard the same personal airplane is the inevitable conversation that arises. Often that conversation can involve operating the airplane—traffic, weather, etc. But it also can be extraneous.

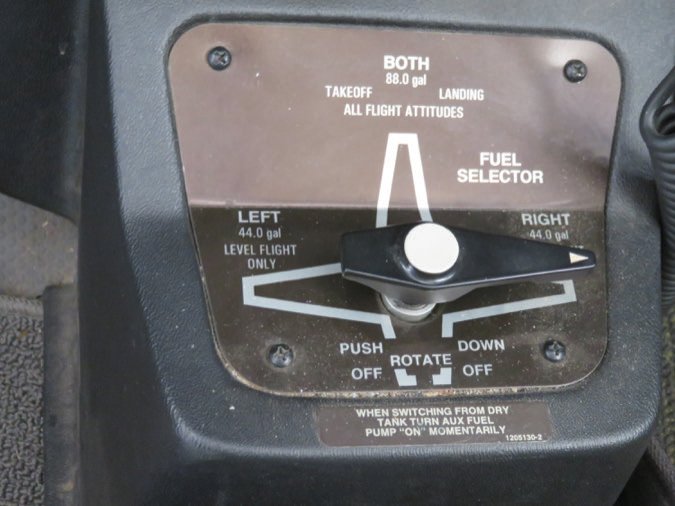

The best example I can give arises from a cross-country flight I made several years ago with another pilot. It was just the two of us aboard, and we had about 3.5 hours from takeoff to landing. The en route portion of the flight was uneventful and featured good VMC. Soon, we were descending for the destination and being vectored to join the final approach. Shortly after making a left turn to align with the runway, at about 1500 feet agl and before performing the pre-landing checklist, the lone engine began to lose power.

My initial spoken reaction can’t be printed here, but I ran through the emergency procedures: mixture full rich, prop to high rpm, full throttle, auxiliary fuel pump on. All that took about five seconds. Then I switched tanks, from the left to the right. The engine roared back to life and we landed without further drama. I had switched tanks only once during the flight, and ran one of them dry while the other one was almost full.

The passenger and I didn’t know each other all that well and took the flight’s opportunity to fix that. Very little of what we talked about involved the flight, however. This oversight on my can part be chalked up to distraction, and could have happened even if the right-seater was not a pilot. But neither of us caught on to the fact I hadn’t switched tanks until the engine reminded us.

Two-Pilot Do’s and Don’ts

Consider these suggestions for managing two-pilot flights:

Do:

- Both pilots must agree who is pilot-in-command.

- Ensure both pilots have a full understanding of what’s expected of them.

- Agree in advance how any in-cockpit disagreements will be resolved, and by whom.

- Always employ the procedure outlined in the sidebar on the previous page when exchanging controls.

- Save critiques or long-winded discussions for when the airplane is straight-and-level in cruise flight or on the ground.

Don’t:

- Don’t fail to fully brief each other on your respective expectations for the flight.

- The PNF should not make decisions properly allocated to the PF during the pre-flight briefing.

- Whomever is designated PIC (not necessarily the PF) must not deviate from the agreed-upon plan without first discussing it with the other pilot.

- If the PNF is handling navigation but not ATC, he or she should stay away from the mic switch.

- Don’t interfere with the PF unless the aircraft is in danger and verbal intervention has failed.

Two-Pilot Checklist

Before starting the engine(s), both pilots should have participated in a complete pre-flight briefing, including evaluation of available weather and discussion of its impact, as well as any procedures necessary to compensate for it and the use of related aircraft equipment.

- Both pilots agree who will serve as PIC (and log the flight time).

- Both pilots agree on the planned route and destination, and ensuring compliance with any special ATC or airspace procedures are considered and assigned to one of the pilots.

- Common cockpit tasks—scanning for traffic, updating weather, communicating with ATC, navigating etc.—are assigned.

- A clear division of labor is established for the preflight inspection. For example, one person unties the airplane while the other inspects fuel, oil and tires.

- Once airborne, any change in plans is fully discussed, agreed to and briefed by the two pilots.

Jeb Burnside is this magazine’s editor-in-chief. He’s an airline transport pilot who owns a Beechcraft Debonair, plus half of an Aeronca 7CCM Champ.