Sports coaches, music teachers, and creative writing instructors all encounter people who just enjoy practicing—sometimes more than they want to play, perform or publish. If you’re one of those folks who find joy in doing turns around a point or steep spirals, more power to you. Go forth, have fun and don’t feel obliged to finish reading this article.

But if you struggled to get the knack of flight maneuver exercises that often seemed far removed from the realities of coaxing an aircraft between Points A and B, you have our sympathy. Training for the private and commercial certificates in particular requires learning to master maneuvers whose relation to practical aviation is, to put it charitably, not obvious. (If you can envision a situation in which your life depends on being able to fly lazy eights to airman certification standards, by all means write in to describe it, as we can’t.) This raises the question: Having once done them well enough to persuade an examiner to issue a certificate, is there any reason to go on spending flight time and the money it represents maintaining those elusive skills?

Sure, hard-core instructors and aviation writers will testify that there’s only good in any activity that extends one’s command of the aircraft. That’s true enough, but the same can be said for keeping your body in peak physical condition, paying off your debts and maintaining correct inflation pressures in the tires of every vehicle you own, down to hangar tugs and wheelbarrows. Reality sometimes has its own ideas. Instead, we’ll fall back on one stock answer that seems to apply to almost everything: It depends. Checkride maneuvers can be grouped into three categories: potentially useful, possibly enjoyable and “Why was this even on the test?”

You Need These

The rationales behind some of the practical tests’ TASKs aren’t the least bit mysterious. Any airplane pilot who can’t land in a crosswind either won’t fly often, or won’t fly for long. Short-field takeoffs may be optional—if offloading payload and waiting for better conditions aren’t enough, you can always call in a mechanic and a flatbed—but in an emergency, a competent short-field landing could be the difference between a good hangar story and extended hospitalization. Steep turns have evident value in avoiding both obstructions and traffic, and a crisply executed chandelle—gaining the maximum possible altitude in a 180-degree climbing turn by reaching stall speed just as the wings return to level—might be the last best chance of escaping a blind canyon. And as much as some of us hate gliding toward a wheat field with the throttle pulled to idle, it’s better to have had recent practice if the engine ever quits for real.

A good case can also be made for the 180-degree power-off spot landing. As we’ve noted before, it’s a performance maneuver rather than a simulated emergency (see “Procedure Vs. Technique” in Aviation Safety’s March 2018 issue). By sharpening awareness of how descent rate is affected by airspeed, bank angle and aircraft configuration, however, the maneuver stands to improve prospects for a successful dead-stick landing.

The value of recurrent single-engine work in twins is obvious. The correct response to an engine failure and the urgency with which it must be made vary widely by phase of flight, hence the need to practice them during the takeoff roll, climbout, cruise and approach. We’d question the wisdom of repeated VMC demonstrations, however. As with practicing stalls to full break, deliberately continuing to bleed off airspeed as directional control decays risks conditioning the wrong response. It’s also one of the more delicate single-engine maneuvers, involving a chance of a genuine aircraft upset that might better be avoided (see the sidebar, “Nothing’s Without Risk,” below). At a minimum, only experienced multiengine pilots should attempt it without instructor supervision.

A much smaller share of helicopters are privately flown, so their pilots are most often constrained by their employers’ training policies. Still, where possible—including in owner-flown aircraft—a few maneuvers deserve more practice than they necessarily get. Normal flights rarely end in run-on landings, but besides being the only option when density altitude exceeds the in-ground-effect hover ceiling, these offer an alternative to autorotation in the event of a stuck pedal or tail rotor drivetrain failure. Those who habitually operate from level surfaces—airports, oil platforms or commercial helipads—can quickly fall out of practice at slope landings, a skill that’s more easily lost than acquired. Of course, regular practice in autorotations—from an assortment of airspeeds, altitudes and approach paths—should be considered foundational, whether done in the aircraft or, when possible, a simulator.

Finally, there are a few maneuvers that, like it or not, you’ll have to demonstrate repeatedly throughout your flying career (see sidebar, “Embrace The Unavoidable,” above). We might as well get in the habit of revisiting them now and again.

Just for Fun?

Admittedly, this category is largely defined by individual taste, and also overlaps a bit with the previous one. A pilot who delights in instrument flying may find nothing more enjoyable than keeping the needles perfectly crossed throughout an ILS—except when doing it partial-panel. The aerobatically inclined are less apt to be thrilled by standard-rate turns and 500-fpm climbs and descents.

Still, some standard VFR maneuvers express more exuberance with less worry than others. Steep turns fit here, too, once you’re reasonably good at them. They’re also a good way of warming up your feel for the airplane before more demanding airwork, not to mention a first step toward satisfying the new passenger who wants to know whether you can do “stunts.” Lazy eights have no obvious practical application, but do let a pilot enjoy the feeling of throwing an aircraft around the sky with little risk of it hitting anything (and are a possible next step if the steep turns left your passenger unimpressed). Flown crisply, S-turns and turns around a point express gratifying precision; the latter also enables you to honor the inevitable request to show your passenger his or her home from the air. (That’s rumored to be the reason this maneuver was added to the test in the first place. Just don’t let yourself get too low, slow or tight—”moose stalls” don’t require an actual moose.)

Meanwhile, much of the fun of flying helicopters is doing things that can’t be done in airplanes. One favorite is to watch the expression on a fixed-wing pilot’s face as you slow the ship to a hover on downwind. Some of the basic warm-up exercises used before training flights—box patterns, pivots and pirouetting down the centerline while air-taxiing—can be highly entertaining. So can steep approaches, maximum-performance takeoffs, and platform or dolly landings…provided they’re well within the pilot’s level of skill. (A dual-fatal California accident in 2015 was triggered by the pilot’s insistence on landing his just-purchased helicopter on a dolly without sufficient transition training.)

We’re Doing This—Why?

The top spot on this list probably goes to eights on pylons. Not only is it another maneuver without obvious relevance to real-world flying—it involves using changes in pitch at a constant bank angle to modulate airspeed with the goal of maintaining a fixed visual alignment between ground references and a reference point on the airframe—but it also involves rapid changes in pitch at low altitude. Both stalls and collisions with obstructions (if the area wasn’t scouted carefully) are real possibilities. A pilot who’s completely comfortable in this situation may be blessed with superior airmanship but could also be saddled with a poor grasp of aerodynamics, little interest in self-preservation or both.

While educated opinions differ, the aforementioned VMC demonstration may belong here, too. Done correctly, it’s slow and controlled but wary, far from an expression of the joy of flight, and the prevalence of unrecovered spins among multiengine instructional accidents (including transition training and flight reviews) suggests that the risks involved aren’t trivial. It’s not clear they’re outweighed by any benefit of repeating this exercise after the checkride or initial transition training.

Helicopter test standards come off relatively well on this count, with no items of dubious relevance. However, some emergency simulations—particularly hydraulic failures and low rotor rpm—are best not practiced solo.

None of the Above

A couple of the required maneuvers don’t fit neatly into any of these categories. Steep spirals are useful under highly specific circumstances—a power failure over a suitable landing spot—but watching rapidly spinning landscape rush toward the windshield isn’t everyone’s idea of fun. Soft-field technique probably belongs in the test standards so pilots who want to fly from grass strips will have some notion of how to do so (and ideally seek additional specialized instruction), but the large number who only fly off pavement probably don’t need to practice it frequently, if at all.

A reasonable rule of thumb is that the more often you fly, and the more varied the conditions and destinations, the less practicing these maneuvers pays off in either safety or proficiency. A pilot who goes cross-country every week or two for business or public benefit is almost sure to stay current on crosswinds, wet runways and atypically steep approaches. If it’s been a year since you did anything beyond the same Sunday breakfast flight to your favorite airport caf, however, your ability to handle the unexpected is probably far less than you remember.

If you’d rather not bother until your next flight review, that’s your right—but expect it to take longer than the regulation one-hour minimum of flight. If you do choose to practice, start with some of the easier items from the “useful” list, move up the difficulty scale as you get things dialed in, then enjoy some of the fun stuff for dessert.

Nothing’s Without Risk

In February 2009, a 1974 Mooney crashed outside Elbert, Colo., killing the solo pilot. Radar data depicted a series of “back-and-forth” maneuvers; the last hit showed a “gentle” right turn at 50 knots and 1300 feet above the ground. Investigators concluded that the 421-hour private pilot—who’d logged 31 hours in the preceding year—had stalled the airplane practicing slow flight in winds gusting to 17 knots.

While unexpected things can happen any time, some flight profiles carry inherently greater risk…with anything done near the ground rising toward the top of the list. Pilots who want to practice maneuvers solo need to have a clear idea of their current abilities (usually less than they once were) and calibrate accordingly. Low-time or rusty aviators particularly need to either stay away from the edge or engage adult supervision.

Every fixed-wing maneuver worthy of the label involves a possible stall, so take that into account, too. Chandelles and lazy eights can be practiced at any altitude, so build in room for stall/spin recovery. Ground reference maneuvers, on the other hand, are by definition done below 1000 feet agl. Unless you know you’re already sharp, caution—and perhaps an instructor’s attention—are strongly recommended.

Embrace the Unavoidable

Given the requirement to complete a flight review every 24 months, there’s a core group of maneuvers you’ll have to brush up at least every other year. (The alternative is to pass another checkride, which might at least involve learning new tricks instead of stumbling through the same ones you’ve bungled all along.) Unless you’re lucky enough to have a CFI familiar with your skills and operations who considers an instrument proficiency check sufficient proof that you can safely exercise your piloting privileges, some standard VFR airwork is going to be part of the drill.

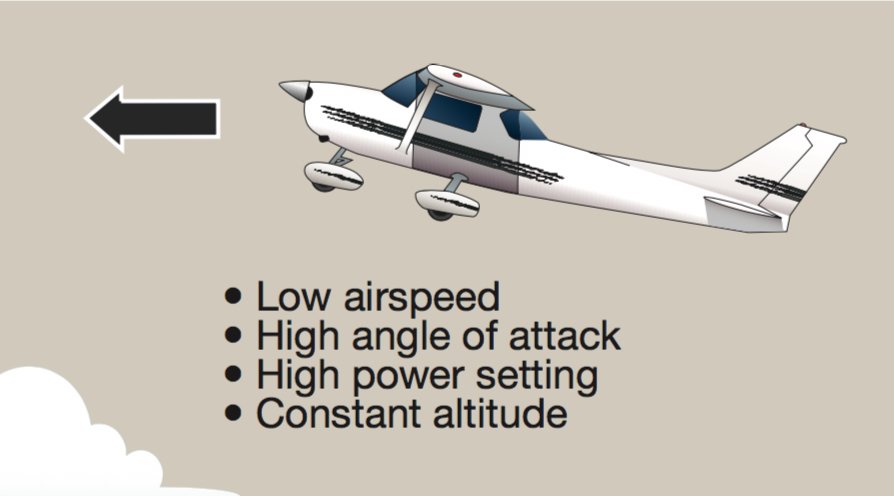

In airplanes, that includes crosswind takeoffs and landings, steep turns, slow flight, go-arounds and at least recognition and avoidance of incipient stalls. (Not many instructors will stop short of a full break unless you fly something with a nasty reputation.) Helicopter pilots can anticipate low-rpm recoveries, governor-off operation in models so equipped, recognition and recovery from settling with power, and of course autorotations. Emergency procedures, including simulated forced landings, are guaranteed in both.

If you’re rusty, it makes sense to practice in advance, solo or otherwise. If you prefer dual, you’ll get the most bang for your buck by choosing a different CFI than the one booked for your review.

Maneuvering Do’s And Don’ts

Losing control of a perfectly good airplane remains the leading cause of fatal accidents in general aviation. A lot of them involve maneuvering flight as opposed to cruising or simple turns to join or leave a traffic pattern.

DO:

• Observe the aircraft’s operating limitations.

• Except for ground-reference maneuvers, perform them with lots of altitude.

• Perform clearing turns and appropriate checklists before each maneuver.

Don’t

• Avoid focusing on the instrument panel; keep your eyes looking outside.

• Don’t rush these maneuvers; they reward smooth control movement.

• Because you’ll often be close to stall speed, don’t pick a gusty day.

David Jack Kenny is a recovering statistician and a fixed-wing ATP with commercial privileges for helicopter. He keeps doing lazy eights in the hope that some day they’ll finally click.