Many instrument-rated pilots struggle to maintain their proficiency for IFR. Logging the six approaches, holding procedures and course intercepts/tracking required by FAR 61.57(c) can be quite the challenge for pilots who fly infrequently or who are based in regions where good weather is routine. Simulators and training devices can be major boosts to maintaining proficiency, especially when focused on maintaining instrument scanning skills and practicing IFR procedures. But when it comes to flying personal aircraft in the clag, there’s nothing that beats practicing in the real thing.

Flying practice approaches to maintain instrument currency is some of the most fun I’ve had in my flying “career.” I’ve made lifelong friendships out of like-minded safety pilots, flown into airports I might not otherwise visit and have many fond memories. I’ve also learned lots about how and how not to go about practicing approaches. The “right” safety pilot is a must—and you’ll also learn from him or her when you fly as their safety pilot. But shrewdly picking your training opportunities also is key.

A Good Safety Pilot

What makes a good safety pilot? First off, he or she must meet requirements to serve as what is effectively the second-in-command. The relevant regulations are summed up in the sidebar on the following page, but that’s only the formal part of the safety pilot equation. There’s also the fact you and the safety pilot will be sharing a close space—thousands of feet in the air, hurtling through it at 90 knots or so—for hours at a time.

So there needs to be some compatibility, beyond just basic skills. For example, he or she should be familiar with the airplane and the airspace you plan to use. Ideally, your safety pilot is in the same boat, also needing practice approaches to maintain currency and proficiency (which aren’t the same). That way, breaking up the duties, sharing expenses and returning the favor is more equitable. There’s also the synergistic benefits of observing someone who’s maintaining the same skill set.

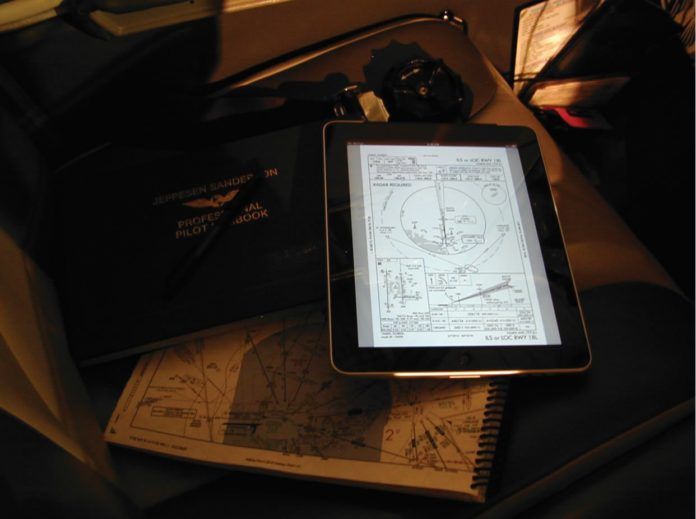

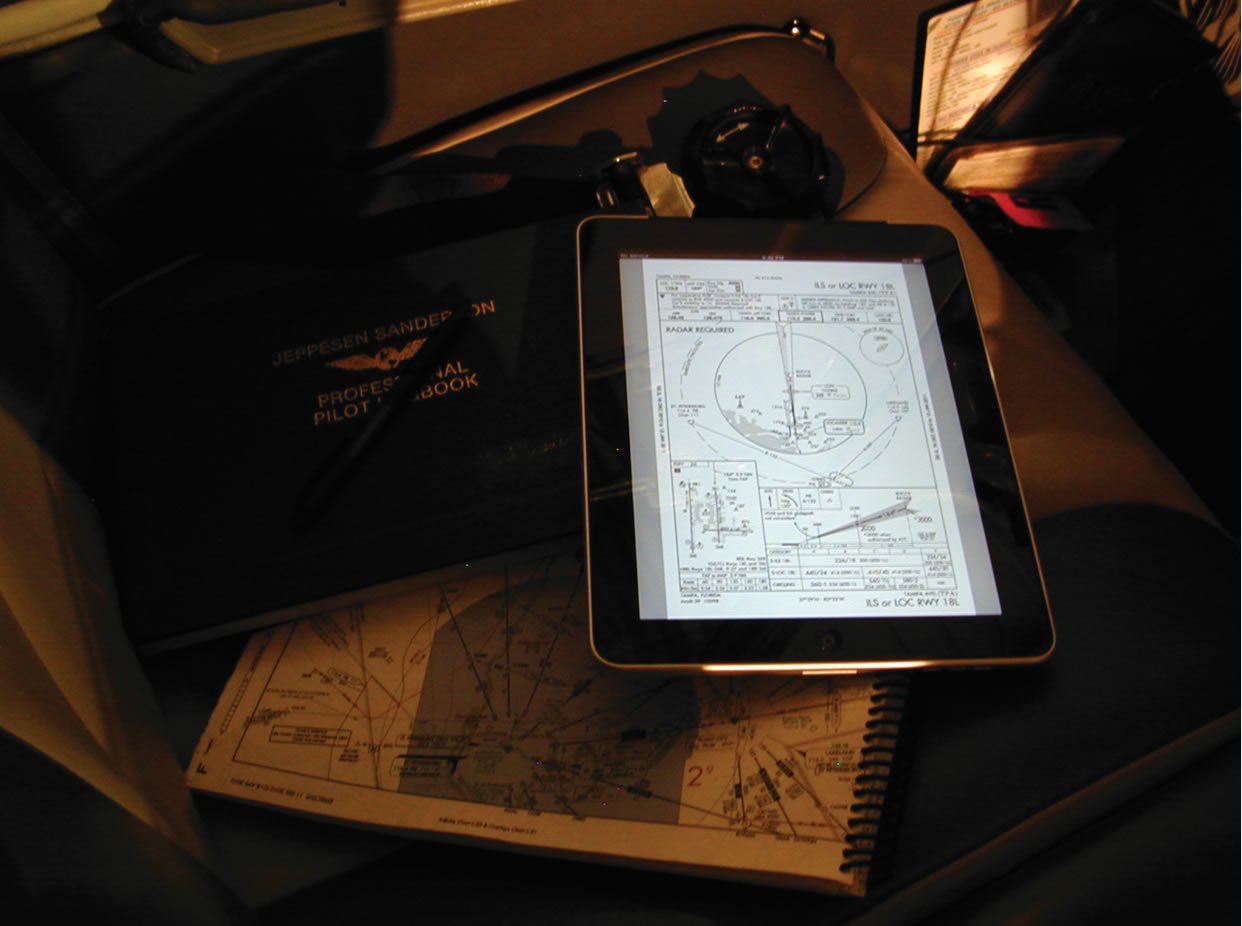

Communication is key: It’s critical in the cockpit, obviously, but also before the flight when discussing The Plan and after it, when you debrief over a cup of coffee at the airport eatery. It also helps if the right-seater has some experience with the chosen airplane’s avionics—someone raised on steam-gauge panels might not understand everything your glass panel is trying to tell you, especially from the other seat. The opposite situation can arise, too, but transitioning from glass to steam seems to be easier than the other way around. These days, you also have to factor in EFB choices as part of the overall avionics picture. Ideally, both front-seaters would have their EFB of choice, especially in busy airspace.

Part of the communication equation is whether the safety pilot understands the role they’ll play. Basically, the safety pilot is there to look for traffic and help prevent the guy or gal under the hood from running into something. The safety pilot isn’t there to help fly the airplane, read checklists, act as an autopilot or program the panel. That’s your job, and you’re supposed to be doing it by yourself, under the hood.

Briefing Your Safety Pilot

Once we’ve established who will be the safety pilot, it’s time for him or her to understand what’s expected of them. As important, they need to know what not to do.

Whatever your plan for this training session, your safety pilot needs to be in on it. He or she needs to know what airports you plan to use and which approaches you plan to fly, plus your expectations for how they’ll terminate: “We’ll do three ILSes at Richmond, miss them all, and return to Stafford for the GPS” might be a plan, but it’s not much for the safety pilot to work with.

If your expectations of a safety pilot go beyond merely looking for traffic and obstacles, before taking off is a good time to explain it all. For example, you may not want them to touch the controls or avionics, preferring to do it all yourself. They need to know that.

You may also choose to use them as sort of non-flying pilot: making radio calls, reading checklists and performing other cockpit chores. Eventually, you become a well-oiled team. And that’s when it’s time to shake things up a bit.

Rolling Your Own?

I earned my instrument rating flying a Piper Archer II out of Washington Dulles International Airport, back when it was practice-approach capital of the world. That also was back when an ADF was considered basic IFR gear and NDB approaches were prevalent. Even though the low traffic level most nights at Dulles meant we often had two miles of runway and the associated approaches to ourselves, that wasn’t good enough for my double-I.

Instead, he made up an NDB approach using a nearby AM broadcast station as the navaid. Lay out the basic courses, distances and altitudes to fly, and you could be shooting an NDB approach to any airport in the world without leaving Virginia. They didn’t count as actual approaches, of course, but they were great practice for nailing the procedures and skills required.

Cobbling together such a procedure doesn’t make much sense these days, if for no other reason than the NDB approach is being phased out in the U.S. And it’s hard to convince a GPS receiver you’re shooting an RNAV approach to, say, Tokyo’s Narita International Airport from over lower Alabama.

But the same basic idea still can apply to practicing VOR procedures, and perhaps even RNAV (GPS) approaches by defining some well-chosen user waypoints. Add an appropriate number of feet to any published altitudes and you also can fly a non-precision approach well above traffic or terrain.

Do The Real Thing

One of the presumptions among pilots seeking currency or proficiency training for IFR operations is that the IFR part always has to be simulated and, yes, simulating IFR with a safety pilot often is the most expedient way to practice approaches. But as long as you’re legal and comfortable with the conditions, there’s nothing preventing you from launching solo when the weather allows and knocking down three or so of the approaches you need to keep pace. But pick your battles with some thought.

Some might view flying an IFR cross-country or shooting approaches at the home ‘drome when the weather is IMC as an extravagance: filing and flying IFR should only be done when necessary. The strain on scarce resources, they might say, abuses the system for selfish purposes. That kind of attitude is unfortunate, and ignores the value of real-world experience without the real-world pressures using a personal airplane for transportation can present.

Picking the days to go get in some instrument approaches, maybe solo, can be an art form. A good day for practicing approaches solo is a “Mama Bear” compromise between plenty of options if the weather caves and bad enough that it counts. In other words, the approaches need to be “loggable” (see the article on page 22), and most of the time you spend aloft is in actual IMC. That usually means something like a 1500-foot ceiling with good visibility underneath, and three or four thousand feet of stratus.

On that kind of day, you can comfortably launch and have plenty of time/altitude to establish your scan and enter the clouds. You’ll get vectored to the facility’s practice approach pattern, or on your way if you’re combining the opportunity into a cross-country. Also, if you’re not feeling comfortable doing it all by yourself, drag along a safety pilot. He or she might learn something, even if they’re not instrument-rated, and you’ll have an extra set of eyes and ears along.

Primary Duty

The safety pilot’s primary role is seeing and helping you avoid traffic and obstacles while you’re “under the hood.” Any other duty, role or responsibility is optional and beyond the traditional safety pilot’s duties, and should be evaluated for the adverse impact it could have on the quality of your training. Yes, a safety pilot should warn you the gear isn’t extended for the landing, but shouldn’t coach you through a missed approach.

The idea is you should be doing this yourself, on your own, with no help from the passengers, just as you would when flying the same approach in for-real weather.

What The FAA Says About Safety Pilots

The FAA’s rules on who can serve as a safety pilot when simulating IMC are specific but broad. They’re found at FAR 91.109(c). Essentially, anyone capable of exercising a private pilot’s privileges and serving as PIC of the aircraft will do. That means a multi-engine rating if you’re flying a twin, but an instrument rating isn’t required when IFR as long as the PIC (that’s you) has one and is current. What about a current medical certificate, meeting the 90-day currency requirement or having had a flight review in the last 24 months?

A medical certificate appropriate to the operation is required, but not by FAR 91.109(c). Instead, according to AOPA’s John S. Yodice, that’s a long-held FAA interpretation of the regulations. “Since a safety pilot is required by regulation to be on board to perform see-and-avoid duties, and since the safety pilot must hold a pilot certificate, under this analysis the safety pilot must hold a current, appropriate airman medical certificate,” he states.

Even though the safety pilot needs a current medical, he or she doesn’t need a recent BFR or 90-day currency, since they apply to the pilot in command, and the safety pilot isn’t PIC.

Simulating Abnormals

Anything worth doing is worth doing well, and that includes practice approaches. We may need to inject some realism into the training, perhaps by failing some gear like the primary nav system, an EFB, the gear or whatever turns your gyros. In any such training environment, everybody needs to be in on the plan.

The parameters of the training need to be explored and explained as well. If you’re simulating a lighting failure at night, for example, under what circumstances, if any, should the safety pilot help with a flashlight? Will he or she help monitor airspeed during one-engine inoperative approaches in a twin?

We’d advocate for the safety pilot doing as little as possible—this is your training session, and they may not be along when something happens for real. Regardless, everyone needs to know their role and understand mutual expectations, and sing out if they see something wrong.